Although the extraction of implanted pacing devices is now a standard activity in electrophysiology laboratories, these procedures are considered to carry a high risk of potentially serious complications.1

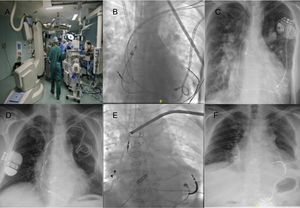

Most extractions can be performed percutaneously using the appropriate tools. However, a small percentage ultimately requires a surgical approach. Additionally, other intermediate situations require both a percutaneous and surgical approach. The availability of a hybrid operating room can enable and facilitate the completion of such mixed interventions in a single surgical procedure. In addition to all of the benefits of a conventional operating room, hybrid operating rooms include an integrated fluoroscopy system that permits procedures based on percutaneous access (Figure 1A).2 Here, by discussing 3 procedures performed between January and November 2017, we present the experience of our group with the use of a hybrid operating room for lead extraction.

A: the hybrid operating room in our center. B and C: a patient with single-ventricle physiology and a dual-chamber pacemaker. D and E: a patient with a dual-chamber pacemaker implanted on the left side and a dual-chamber implantable cardioverter-defibrillator implanted on the right side.

The first case involves a 32-year-old woman with single-ventricle physiology and a dual-chamber transvenous pacemaker implanted in 2013 due to atrioventricular block (AVB). After the implantation, the patient developed recurrent strokes, despite adequate oral anticoagulation. Because the embolic strokes were suspected to be originating at the pacemaker leads, we decided to replace the endocavitary leads with epicardial ones. The procedure was performed in the hybrid operating room; first, the epicardial leads were implanted via thoracoscopy (Figure 1B); then, both transvenous leads were percutaneously removed by means of separate locking stylets (LLD, Spectranetics) and a mechanical extraction sheath (TightRail 9 Fr, Spectranetics), and complete extraction was achieved (Figure 1C).

The second case concerns a 58-year-old man with a DDD pacemaker introduced through the left subclavian in 2007 due to AVB. In 2015, a dual-chamber implantable cardioverter-defibrillator was implanted on the right side in a second hospital center due to ventricular arrhythmias. The right side was used due to occlusion of the left subclavian vein, and the left side leads were left in place. The patient was referred to our center due to endocarditis of the pacemaker/implantable cardioverter-defibrillator lead with positive blood cultures and positive positron emission tomography-computed tomography (Figure 1D). Given that the patient was dependent on the pacemaker and had potentially infected bilateral leads, we decided to implant epicardial leads and percutaneously extract all of the endocardial leads in the same procedure. An epicardial pacing lead was implanted in the left ventricle with a defibrillation coil through a left minithoracotomy. Another epicardial lead was implanted in the right atrium via a right minithoracotomy. The leads on the right side were then percutaneously extracted using separate locking stylets (LLD, Spectranetics) and a mechanical extraction sheath (TightRail 11 Fr, Spectranetics). Finally, both leads on the left side were removed with an LLD locking stylet and a 9 Fr mechanical sheath (Figure 1E and F).

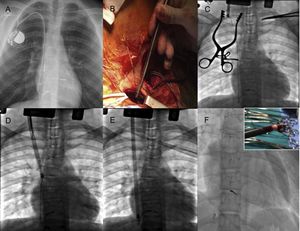

The final case involves a 14-year-old boy with a perimembranous ventricular septal defect, treated in 2003, and a right-sided VVI pacemaker implanted due to postoperative AVB. Ventricular lead fracture was documented in June 2017 and a new ventricular pacing lead and an atrial lead were implanted to restore atrioventricular synchrony. During this implantation, an abortive attempt was made to remove the previous lead; however, the lead had been implanted through the right jugular vein and it was not possible to align the extraction tools with the axis of the lead (Figure 2A). The patient subsequently developed an uncomplicated pouch infection, and complete percutaneous removal of the device was scheduled in the hybrid operating room, after surgical facilitation of access to the ventricular pacing lead implanted in 2003. First, the pacemaker pouch was opened and the recently implanted right atrial and right ventricular leads were extracted by simple traction. Then, through a second supraclavicular incision, the origin of the fractured ventricular lead in the right jugular vein was reached and its proximal end was extracted from the generator pouch to the supraclavicular incision (Figure 2B). Once exposed, a lead extender (Bulldog, Cook Medical) was used and a mechanical sheath (Shortie, Cook Medical) was introduced to release the proximal adhesions (Figure 2C and D); this sheath was subsequently replaced with a longer sheath (Evolution 13 Fr, Cook Medical) (Figure 2E). Finally, the lead was successfully extracted; although a small fragment (length < 2cm) remained in the ventricle, it was considered a complete extraction due to its distal location (Figure 2F).

Because interventional procedures can be performed in a hybrid operating room, although usually with portable fluoroscopy systems of lower image quality, this type of room has clear advantages over a conventional operating room for these procedures. In contrast, electrophysiology laboratories are usually not prepared to house all of the equipment necessary to perform cardiac by-pass surgery under optimal conditions.

The patients presented here are 3 clear examples of the possible indications for lead extraction in a hybrid operating room: a) when epicardial lead implantation is required and it can be performed in the same procedure, and b) when an alternative nonstandard access is required for lead extraction. The advantages of this multidisciplinary approach are undoubted because it allows the implantation of epicardial leads at any stage of the procedure, surgical removal if there is failure of the percutaneous route, and, ultimately, the performance of complex procedures in a safe environment for the patient.