Population aging and the higher prevalence of chronic diseases have forced health systems to rethink the way they offer services to make them more effective. Often primary care (PC) and specialized care (SC) do not join forces due to lack of motivation, commitment, and mutual coordination. This has a negative impact on the continuity of care and inefficiencies in resource use, and also brings into question the system itself.1 Our hospital serves a population of 548 223 inhabitants. It caters to outpatients in specialized units (hospital) and general clinics in 2 PC centers (25 patients per clinic). When echocardiograms are requested, the patients are usually referred to the hospital. Overall, 31.5% of the specialists’ time is dedicated to general outpatient clinics.

A pilot project was undertaken to assess whether migration from the classic model for cardiology care to an integrated PC model that combines a one-stop visit (OSV, outpatient clinic with echocardiography), a consulting cardiologist, and a virtual clinic (VC) reduces in-person visits and delays. In addition, we investigated whether the model can define which patients with stable chronic disease can be followed up in PC.

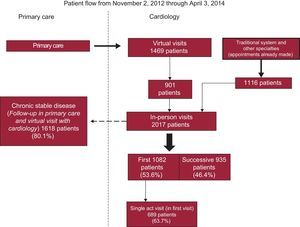

A prospective descriptive study was undertaken (between November 2012 and April 2014). Patients who were referred virtually (with digital electrocardiogram and electronic clinical record) were assessed. The cardiologist decided whether an in-person appointment was necessary. A working group decided which patients with stable chronic disease could be attended in PC (under supervision of the cardiologist via VC) and developed consensus protocols. OSV was defined as a single care action in which diagnosis and treatment were established after performing the additional tests available with this new model in the first visit. As additional resources, this model needs a digital electrocardiogram recorded in PC and an echocardiogram recorded in the cardiology clinic. The administrative area (chosen as it was the only area with digital electrocardiography available) served a population of 33 805 inhabitants. Patients referred by PC through a VC, those who already had an in-person appointment before starting the study (who migrated from the traditional model), and those referred from other specialties were included. Initially, the clinic worked 5 days a week (10 VCs of 5minutes each and 12 in-person appointments of 20minutes each: 6 first visits then 6 successive visits). A patient was defined as having chronic stable disease after 3 in-person visits and a 1-year follow-up with no hospital admissions.

There were 2017 in-person visits, 53.6% of which were first visits (and of these 63.7% were the only visit) and 46.4% were successive visits. The requested echocardiograms were performed in the same visit in 97.5% of the patients. Of patients attended in person, 80.1% entered follow-up in PC with virtual follow-up by a cardiologist. There were 1469 patients attended in the VC. An in-person appointment was made for 61.3% of these. During this time, the in-person visits of 89 patients were discussed in a VC (4.4%) and these patients then entered follow-up in PC (Figure). At the end of the project, the delay for an appointment in person was 72hours compared with a median of 53 days with the conventional system. Currently, this clinic is in operation 3 days a week.

Five consensus protocols were drafted with PC: atrial fibrillation, heart failure, hypertension, valve disease, and ischemic heart disease. These protocols indicated the clinical treatment, referral pathways, and the group of patients with stable chronic disease who could be attended in PC (provided access to the cardiologist was available via VC). Currently, the new care model has been extended to an additional population of 71 002 inhabitants (5 health care centers in operation 4 days a week with different cardiologists). One year after implementation, a delay of less than 3 weeks has been achieved, with similar outcomes in terms of OSV and the percentage of echocardiograms performed during the visit itself (likewise, this population migrated from the traditional system).

The patients benefitted from being attended by a cardiologist, both as the person directly responsible for their care and as the consulting specialist. Our specialty can perform most of the required complementary tests, making it one of the most appropriate for OSV.2

Olayiwola et al.3 showed that electronic consultations can reduce VC and delays without increasing adverse events. Most visits in a SC cardiology center are referrals from PC: liaison between these 2 levels is indispensable for efficient health care.4 This pilot project has encouraged integration of PC and SC through an OSV, a consulting cardiologist, and a VC. In the study by Falces et al.,5 the consulting cardiologist plays a leading role. The cardiologists in each SC clinic are proposed as the consultant for PC physicians who refer patients to them. With the VC, dialogue between PC and SC is increased, with greater decision-making capacity. However, the degree of user satisfaction should be assessed and studies of costs and of differences in morbidity and mortality in comparison with the previous model should be undertaken. In 2017, it is expected that 80% of the catchment area will switch to this new care model. Likewise, as experience accrues, the protocol for integration with PC, as well as the material resources necessary to generalize this model to the entire autonomous community, are being updated. The challenge is to build a health care scenario that integrates the 2 levels of care.

.