Patients with severe mental disorders often have several comorbidities and are prescribed a large number of drugs, making them susceptible to the development of medication-related problems.1 Care of their physical health should form part of the overall therapeutic approach used in this population. Preventive measures should be established to avert risk situations, such as the development of potentially life-threatening adverse events, including those associated with the use of medication that affects cardiac conduction. It is important for physicians to be aware of the adverse cardiovascular events associated with drugs used for cardiac and noncardiac diseases, as well as their potential interactions.2

Conduction changes can manifest as an acquired prolongation of the QT interval on electrocardiography (ECG), the most common cause of which is drug-related. This abnormality is a recognized risk factor for sudden death secondary to ventricular arrhythmias such as torsade de pointes.3 In addition, conduction blocks can occur, as has been described with lithium use.4 Complete left bundle branch block (LBBB) is a potential marker of severe heart disease, although in some cases it is not associated with recognizable structural abnormalities and shows a characteristic ECG pattern.

We describe the case of a 56-year-old man. Strict cardiac monitoring carried out in our center detected a new-onset LBBB during formoterol treatment that resolved following discontinuation of the drug. The ECG monitoring protocol used has been included in the 2015 Best Practice Guidelines of the Spanish Health System, approved by the SHS Interterritorial Council of April 13, 2016.5

The patient had no hypertension and no known heart disease. He was diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia, hyperthyroidism, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and was receiving treatment with clotiapine 40 mg/d, clorpromazine (40 mg/mL) 250 drops/d, levothyroxine 25 μg/d, omeprazole 20 mg/d, acetylcysteine 600 mg/d, calcium/vitamin D 600 mg/1000 IU in 1 tablet/d, and ipratropium bromide 18 μg/d. Follow-up ECGs since admittance had yielded normal results, with the last recordings showing sinus rhythm at 70 bpm, no atrioventricular or branch blocks, and QTc 399 ms.

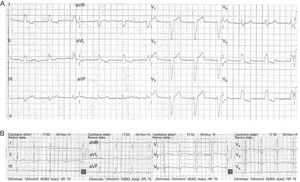

At 7 months following admittance to our center, the patient was started on treatment with formoterol 12 μg/d because of poor control of his chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, with symptom improvement. At 7 days after initiation of this treatment, ECG examination detected a new-onset LBBB, with sinus rhythm at 70 bpm and QTc 438 ms (Figure). In addition, the patient reported chest pain at rest of 5 minutes’ duration on various occasions during the previous 4 days, which prompted his urgent referral to the reference center. Serial troponin T determinations were negative and stress transthoracic echocardiography disclosed no relevant structural heart disease, thereby excluding an acute coronary syndrome. The patient was discharged with a diagnosis of mechanical chest pain and a recommendation for cardiologic follow-up. Upon his return to our center, formoterol treatment was stopped. At 10 days after discontinuation of the drug, a new follow-up showed resolution of the LBBB with QTc measuring 433 ms and heart rate at 78 bpm.

On application of the Naranjo6 algorithm to analyze the causal relationship between formoterol administration and the appearance of the adverse reaction, the relationship was deemed “probable”. The case was notified to the Spanish Drug Surveillance System.

The José Germain Psychiatric Institute of Mental Health Services is a publically-funded health center that provides specialized mental health care. Since 2013, an internal protocol has been in operation to prevent iatrogenic sudden death secondary to pharmacological treatment. At admission, all patients undergo a systematic evaluation, including ECG, by internal medicine specialists. The QT interval value is corrected according to the heart rate (corrected QT [cQT]), using the Bazzet formula in patients whose heart rate is 40 to 80 bpm and the Friedericia formula for other rates.3 After the baseline examination, periodic ECG monitoring is carried out, according to the characteristics of the individual patients and the pharmacological treatment they are receiving. The aim is to monitor QT segment prolongation and other heart rhythm abnormalities.

Since implementation of ECG monitoring of patients admitted to our center, several cases of drug-related QT interval prolongation have been identified and reported to the Spanish Drug Surveillance System. However, this is the first time new-onset LBBB has been detected in association with administration of a drug.

Although an acute coronary syndrome was ultimately excluded in the case described, we believe it is important for psychiatric centers to have protocols designed to detect cardiac risk situations that may have a fatal outcome. It is recommended to include ECG monitoring in patients with severe mental disorders to improve the safety of their health care. All patients receiving several medications are at higher risk of experiencing potentially serious adverse events due to drug interactions that may go unnoticed by the treating clinician.2