We present the case of a 27-year-old woman admitted to our hospital for heart failure. When she was 5 months old, she was admitted for acute heart failure. Echocardiographic studies showed a dilated cardiomyopathy with severely depressed left ventricular ejection fraction with subsequent recovery in the follow-up and the patient was diagnosed with myocarditis. She had nystagmus, cone-rod dystrophy, and atrophy of the optic pathway from the first months of life with bilateral blindness and perceptive hearing loss since adolescence. She had had a history of obesity since childhood and was diagnosed with type 2 diabetes and hypertriglyceridemia at 14 years of age. All these findings raised the alarm for a mitochondrial encephalopathy but muscle biopsy and Sanger genetic study were negative for the A8344G mutation point involved in mitochondrial encephalomyopathy, lactic acidosis, and stroke-like episodes (MELAS), and myoclonic epilepsy with ragged-red fibers (MERRF).

At the current admission, the patient complained of dyspnea for the past few months that progressed to New York Heart Association functional class III/IV.

Transthoracic echocardiography revealed mild left ventricle dilatation with severe systolic dysfunction without areas of hypertrabeculation, hypertrophy, or thinned myocardial areas after administration of echocardiographic contrast. The patient progressed favourably with standard medical therapy with resolution of congestive symptoms and was discharged with a scheduled magnetic resonance imaging to complete the assessment of her dilated cardiomyopathy.

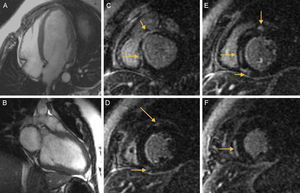

The presence of a dilated left ventricle with severe systolic dysfunction was confirmed at magnetic resonance imaging, with pathological contrast enhancement in the subepicardial region at the insertion point of both ventricles and with intramyocardial enhancement at the septal middle segment, compatible with myocardial fibrosis (Figure A, Figure B, Figure C, Figure D, Figure E and Figure F).

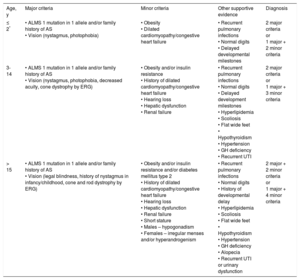

On the basis of these findings, and after previous exclusion of a mitochondrial disease with a high degree of certainty, Alström syndrome was diagnosed as the patient met the clinical diagnostic criteria (Table). Genetic study by next-generation sequencing was requested for the ALMS1 gene, which is involved in this disease. This study was positive for 2 mutations on exons 8 and 11 of the gene with pathogenic significance establishing the definitive diagnosis.

Marshall's Age-specific Diagnostic Criteria

| Age, y | Major criteria | Minor criteria | Other supportive evidence | Diagnosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤ 2* | • ALMS 1 mutation in 1 allele and/or family history of AS • Vision (nystagmus, photophobia) | • Obesity • Dilated cardiomyopathy/congestive heart failure | • Recurrent pulmonary infections • Normal digits • Delayed developmental milestones | 2 major criteria or 1 major + 2 minor criteria |

| 3-14 | • ALMS 1 mutation in 1 allele and/or family history of AS • Vision (nystagmus, photophobia, decreased acuity, cone dystrophy by ERG) | • Obesity and/or insulin resistance • History of dilated cardiomyopathy/congestive heart failure • Hearing loss • Hepatic dysfunction • Renal failure | • Recurrent pulmonary infections • Normal digits • Delayed development milestones • Hyperlipidemia • Scoliosis • Flat wide feet • Hypothyroidism • Hypertension • GH deficiency • Recurrent UTI | 2 major criteria or 1 major + 3 minor criteria |

| > 15 | • ALMS 1 mutation in 1 allele and/or family history of AS • Vision (legal blindness, history of nystagmus in infancy/childhood, cone and rod dystrophy by ERG) | • Obesity and/or insulin resistance and/or diabetes mellitus type 2 • History of dilated cardiomyopathy/congestive heart failure • Hearing loss • Hepatic dysfunction • Renal failure • Short stature • Males – hypogonadism • Females – irregular menses and/or hyperandrogenism | • Recurrent pulmonary infections • Normal digits • History of developmental delay • Hyperlipidemia • Scoliosis • Flat wide feet • Hypothyroidism • Hypertension • GH deficiency • Alopecia • Recurrent UTI or urinary dysfunction | 2 major + 2 minor criteria or 1 major + 4 minor criteria |

AS, Alström syndrome; ERG, electroretinogram; GH, growth hormone; UTI, urinary tract infections.

Our patient was the first case of this disease to be described in her family. Genetic study for these mutations were negative in her parents and, for this reason, she seems to have a spontaneous mutation on this gene.

Currently the patient is 29 years old and is in New York Heart Association grade I/IV without new episodes of decompensation, despite persistant severe left ventricular systolic dysfunction in follow-up visits.

Alström syndrome (AS) was first described in 1959 by Alström et al.1 It has a prevalence of < 1/100 000.1,2 Alström syndrome is a rare genetic autosomal recessive disease characterized by multisystemic involvement and produced by a mutation in the ALMS1 gene located on chromosome 2p13.3 This gene encodes a protein whose mutation leads to progressive fibrosis of various organs characterized by cone-rod dystrophy, hearing loss, childhood truncal obesity, insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia, type 2 diabetes, hypertriglyceridemia, short stature in adulthood, cardiomyopathy, and progressive pulmonary, hepatic, and renal dysfunction. Symptoms first appear during childhood and the progressive development of multiorgan pathology reduces life expectancy.2–4 Prior to the discovery of ALMS1 mutations, the diagnosis was made solely based on phenotype. However, the high degree of variability, even within families, creates difficulties for a universal definition.5 Marshall defined AS using age-specific criteria (Table).6

Ocular involvement is a cardinal sign of AS1,5,6 that leads to progressive visual dysfunction and blindness, usually during the second decade of life. In addition, around 80% will develop neurosensorial hearing loss that will progress throughout life.4–6

Childhood obesity is a common and early manifestation. It is usually accompanied by a characteristic phenotypic expression and affected individuals often develop type 2 diabetes with insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia, as well as hypertriglyceridemia. For these reasons, the metabolic profile leads to an increase in cardiovascular risk.1,5

Cardiac involvement is characterized by the development of dilated cardiomyopathy with systolic dysfunction, myocardial fibrosis, and decreased myocardial mass.2,3 Cardiac involvement is a common manifestation, the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in these patients and the first cause of death in childhood. It can manifest as acute heart failure at any time of life, although the onset is often in the first weeks or months of life as the first manifestation, as in our case.2–6 Subsequent recovery of cardiac function is common as well as recurrence during adolescence or adulthood.2,5

The prognosis is variable and will depend on the progression of the involvement of the different organs and systems. Life expectancy is usually less than 50 years.5 Although there is no specific treatment, and measures should be targeted to treat damage to each of the different systems, early diagnosis, a multidisciplinary approach and appropriate prevention strategies will slow progression and thereby improve patient survival.2,3,5

Genetic syndromes are often difficult to diagnose and in most cases lack a specific treatment. A high degree of suspicion is crucial to establish the diagnosis, which will not only allow us to improve the care of our patient, but will also be necessary to provide genetic counselling and screening of family members, if indicated.