The aortopulmonary window (APW) is a defect resulting from incomplete separation of the walls of the main pulmonary artery and aorta at the conotruncal septum during early embryogenesis. It is an uncommon condition, accounting for 0.2% to 0.6% of all congenital heart diseases.1

APW has traditionally been treated by surgery. The first treatment by transcatheter closure was carried out in the 1990s using a double umbrella occluder system.2 Since that time, reports of transcatheter APW treatment with these devices have emerged only sporadically.3–5 An excessively wide diameter at the pulmonary or aortic ends makes transcatheter closure technically demanding, and therefore, this alternative option is little used.

We present our experience with transcatheter APW closure from July 2004 to December 2017. Six patients were referred for closure with an occluder device (Figure 1). Mean age was 4.3 years (1 month-15 years) and weight was 30 (3–45) kg. The median pulmonary artery systolic pressure was 50 (25–80) mmHg, with a pulmonary vascular resistance of 3.7 (2.1-4.5) WU and a left-to-right shunt (Qp:Qs) of 3:1 (1.5-4.56), reflecting unrestricted pulmonary flow through the defect. The defects considered for transcatheter closure were type 1 according to the classification of Mori et al.6 The median diameter of the aortic orifice was 6.7 (2.31-14.9) mm. In all patients, the pulmonary arterial pressure decreased following closure with the device. Duration of hospital stay after the procedure was 3 (1–6) days (Table 1). During the first 24hours, 2 patients experienced device embolization. Both patients underwent a new transcatheter procedure in which the device was retrieved and removed, and a larger one implanted to occlude the defect. Another child, treated during the first month of life, required placement of a second device 1 year later because of a considerable residual shunt. Median clinical follow-up was 6 (2–11) years. The estimated pulmonary artery systolic pressure on echocardiography was 28 (16-43) mmHg. There were no gradients indicative of obstruction at the aorta or pulmonary branches.

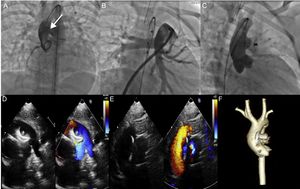

A. Aortography at the aortic root shows a large aortopulmonary window (arrow). B. Angiography of the pulmonary artery. C. Properly positioned occluder device, with no residual shunt. D and E. Echocardiogram shows slight protrusion of the device toward the main pulmonary artery and the retention disc in the ascending aorta, which does not generate a significant obstruction gradient. F. Computed tomography control shows a properly positioned occluder device.

Transcatheter Closure of Aortopulmonary Window in Instituto Nacional de Cardiología Ignacio Chávez

| Age,a months | Weight,a kg | Size of defect, mm | PASP, mmHg | Device, mm | Complications | Follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9 | 6.1 | 2.3 | 25 | ADO 5/4 | None | Asymptomatic |

| 180 | 45.0 | 4.1 | 30 | ADO 10/8 | None | Asymptomatic |

| 19 | 8.4 | 4.4 | 30 | ADO 8/6 | None | Asymptomatic |

| 0.7 | 3.1 | 5.8 | 80 | ADO II 6/4 | None | Residual shunt (closure with ADO II 4 × 4 mm) |

| 55 | 15.0 | 8.4 | 80 | ADO 14/12 | Embolizationb | Asymptomatic |

| 37 | 14.2 | 14.9 | 60 | Cera 16/18 | Embolizationc | Asymptomatic |

ADO, Amplatzer persistent ductus arteriosus occluder device; ASO, Amplatzer atrial septal defect occluder device; PASP, pulmonary artery systolic pressure.

During the same period, APW was surgically treated in 7 pediatric patients: median age was 6.8 (1-25) years and weight 17.8 (7-54) kg. The defect was classified as type I in 2 patients, type II in 2 others, and type III in the remaining patients.6 Transcatheter closure was not considered in those with a type I morphology because of the large size of the defects (> 20mm). A bovine pericardial patch was used for closure in all patients. The mean duration of hospitalization following the procedure was 7 days.

With the advances in the development of devices for closure of various congenital heart defects, such as persistent ductus arteriosus and ventricular or atrial septal defects, it is surprising that transcatheter APW closure still plays a very small role. This approach has several attractive advantages: extracorporeal circulation is avoided during the procedure and the postoperative hospital stay is shorter. However, the excellent outcome achieved with surgery and the technical complexity of transcatheter closure are the 2 main reasons why most centers prefer surgical treatment. Regardless of these considerations, the candidates for transcatheter closure should have relatively small defects located at a point equidistant between the bifurcation of the pulmonary artery and the semilunar valves, and far from the left coronary artery ostium and the aortic valve; that is, type I defects according to the classification of Mori et al.6 It is important to appropriately characterize the defect through the use of several angiographic views or even measurement balloons to precisely determine the dimensions of the window.3–5 It is also a challenge to choose the appropriate device, and to date, there is no consensus on the choice of an optimal device for APW closure. Ductus arteriosus occluders tend to protrude toward the main pulmonary artery and carry a risk of obstructing the vessel, whereas atrial septal defect occluders are bulky for this purpose and may injure or obstruct the semilunar valves or left coronary ostium.5 Trehan et al.3 considered that the perimembranous ventricular septal defect occluder device may be the most appropriate. It has a relatively flat profile (waist diameter, 1.5mm), which could cause less obstruction. Furthermore, because the discs are asymmetrical, they can be used to close an APW with a relative deficiency of one of the borders.

In selected patients, percutaneous APW closure can be considered a viable, effective procedure. Nonetheless, the potential risks should be considered, such as device embolization and residual shunts. Because of its excellent results, surgical management remains the method of choice for treating these defects.

.