Although clinical progress is favorable in most patients with tako-tsubo syndrome with resolution of ventricular dysfunction, complications leading to shock sometimes occur.1

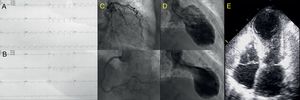

We present the case of an 83-year-old woman, with no medical history of interest, who consulted for a 12-hour history of oppressive central chest pain with no clear triggering factor. An electrocardiogram showed ST-segment elevation in V3-V6, DII, DIII, and aVF (Figure 1A). An ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome was suspected, and a loading dose of dual antiplatelet therapy was administered (300mg aspirin and 600mg clopidogrel). Emergent coronary angiography showed no significant lesions in the epicardial arteries (Figure 1C). The study was completed with ventriculography, which showed apical akinesia (Figure 1D), and transthoracic echocardiography, which depicted akinesia of the left ventricular middle and apical segments (Figure 1E). Left ventricular ejection fraction was 35%, with hypercontraction of the basal segments, and the mitral valve showed a systolic anterior movement (SAM), without significant flow acceleration in the left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT), and a mild (< 10mm), circumferential pericardial effusion (PE).

The patient was hemodynamically stable, showed no evidence of heart failure, and had a minimal troponin I elevation (peak 0.823 ng/mL); nonetheless, at 24hours she began to show hemodynamic deterioration. Transthoracic echocardiography detected an increase in the dynamic LVOT obstruction2 and progression of the PE (18mm in the right ventricular free wall) (Figure 2A), with no echocardiographic signs of cardiac tamponade. Based on these findings, fluid therapy was increased and phenylephrine and esmolol infusion was started. These measures led to a decrease in the dynamic LVOT obstruction and improvement of the patient's hemodynamic status. In light of the PE increase, cardiac computed tomography was performed, but there was no evidence of cardiac rupture. However, an aneurysmal dilatation of the left ventricular apical region was detected, with preserved myocardial thickness and a thrombus adhering to the inferoapical segment (Figure 2B).

In the following hours, the patient's clinical course was unfavorable, with the development of severe cardiogenic shock (hypotension, anuria, elevated lactate), worsening of the dynamic LVOT obstruction (Figure 2C), progression of PE (21mm), and evidence of tamponade (partial collapse of the right chambers in diastole and a change in the transtricuspid flow > 50%). Pericardiocentesis was performed, yielding 350mL of hematic fluid (hemoglobin, 9.9g/dL). Because the increase in PE was gradual and cardiac computed tomography showed no evidence of cardiac rupture, we adopted an expectant attitude regarding the etiology of the hemopericardium. Nonetheless, aspirin administration was discontinued (opting for single antiplatelet treatment), as well as the enoxaparin 40mg/d. A slight improvement in the patient's hemodynamic status was achieved following pericardiocentesis, but she remained in cardiogenic shock and consequently initiation of circulatory support was evaluated. Use of an Impella support device (Abiomed) was contraindicated because of the intraventricular thrombus, and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation was rejected due to the patient's advanced age. An intra-aortic counterpulsation balloon was implanted and the amines were optimized to maintain mean blood pressure at > 60mmHg, but the tissue hypoperfusion and anuria persisted, requiring the start of continuous venovenous hemofiltration. The patient's condition slowly improved without the application of additional measures, and we were able to discontinue the counterpulsation balloon, hemofiltration, and intravenous drugs at 72hours after the onset of the clinical situation. The patient's evaluation was completed with a magnetic resonance study, which showed no signs of myocardial necrosis on delayed enhancement sequences; we identified only a focal pericardial hypersignal in the anteroapical region (Figure 2D). After 10 days of hospitalization, the patient was discharged with preserved left ventricular systolic function. At the 3-month follow-up examination, she was in New York Heart Association functional class I, with preserved overall and segmental left ventricular systolic function and persistence of the electrocardiography changes (Figure 1B).

The development of PE is not unusual in tako-tsubo cardiomyopathy, but it rarely requires drainage. We found only one case of hemopericardium in the literature, and the authors suggested that inflammation and high doses of antithrombotic treatment may have had an impact on the genesis of the effusion.3 This theory is supported by the clinical course of our patient and the magnetic resonance findings.4. In addition, our patient is the first showing dynamic LVOT obstruction, cardiac tamponade, and intraventricular thrombosis simultaneously. The reversibility of the syndrome, as well as the potentially deleterious effect of inotropic amines and vasopressors, would support prompt use of short-term circulatory assistance if there is hemodynamic instability. Of note, the mean age at the onset of tako-tsubo cardiomyopathy (70 ± 12.5 years in the RETAKO national registry)5 should lead to a reconsideration of circulatory assistance protocols, which often exclude patients of advanced age.

.