Clinical practice guidelines recommend establishing regional networks as the most appropriate system for attending patients with ST-elevation acute coronary syndrome.

Data are available on the minimum number of primary percutaneous coronary interventions (PPCIs) per center and operator to guarantee appropriate care.1 However, little has been published on the maximum catchment population per center. Excessively large catchment populations may lead to patient overlap, overload of the on-call teams, saturation of beds for acute events in the recipient hospital, and interference with elective percutaneous interventions. Although the European Cardiology Society suggests an average population size of half a million inhabitants (with a lower limitof 0.3 million and an upper limit of 1 million),2 the actual figures in Europe range from 31 300 to 6 533 000 inhabitants.3

In the design of the network in the Spanish region of Asturias in 2011, there was debate about the need to concentrate all activity in a previously existing center or to take advantage of the opening of a second center to distribute the population. In the end, the latter option was chosen. During this debate, it was decided to analyze the percentage of patients with an indication for PPCI who had overlapped in time in our region, and who would have experienced a delay in the door-to-balloon time on account of all the activity being concentrated in the initial center.

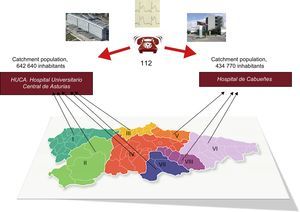

Asturias has a population of 1 077 410 inhabitants and 8 health districts (Figure). The regional plan establishes that districts I and II, with populations of 48 788 and 29 484 inhabitants, respectively, conduct fibrinolysis in a nonhospital setting, if possible, with immediate transfer to the Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias in Oviedo, given that a first contact-balloon time < 120min would not be possible. In the remaining 6 districts, with a population of 999 138 inhabitants, PPCI is the option. Of these, districts III, IV, and VII are referred to Oviedo while the remaining 3 districts, V, VI, and VIII, are referred to the Hospital de Cabueñes, in Gijón. Oviedo has 2 rooms in operation from 8:00 am to 3:00 pm and 1 room in operation from 3:00 pm to 10:00 pm on week days, but with an additional on-call team, so that on week days from 10:00 pm onwards, 2 emergencies can be attended at the same time. In contrast, Hospital de Cabueñes can only provide coverage for a single patient at a time. With this structure, PPCI is available to 92.8% of the population, while only 7.2% are covered by fibrinolysis.

Between May 1, 2013 and April 30, 2014, the time between activation of the catheterization team and the end of the procedure was analyzed for all PPCIs performed in the region. The percentage of patients who overlapped in time and who, for this reason, had experienced a delay in reperfusion was calculated. Because 1 of the 2 centers had 2 rooms, if 2 patients overlapped during daytime on week days in this center, they were not considered as coincident.

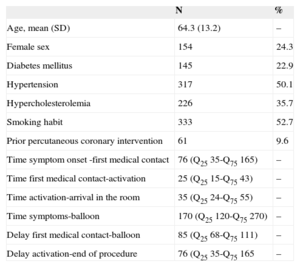

In total, 632 activations were recorded, that is, 590 activations per million inhabitants. In 531 of these cases, PPCI was performed, corresponding to 84.1% of the total number of activations and 496 PPCI per million inhabitants. The patients’ clinical characteristics and the activation times are presented in the Table. Of the 632 activations, 104 procedures (16.5%) were performed with overlap in the reported interval, which would have meant the procedure was delayed in 1 out of every 2 patients (52 cases, 8.2%). Counted according to PPCI, of these 104 cases, PPCI was performed in 92, and so 46 patients may have experienced a delay in reperfusion, that is, 7.2% of the overall series.

Clinical Characteristics and Delays

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 64.3 (13.2) | – |

| Female sex | 154 | 24.3 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 145 | 22.9 |

| Hypertension | 317 | 50.1 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 226 | 35.7 |

| Smoking habit | 333 | 52.7 |

| Prior percutaneous coronary intervention | 61 | 9.6 |

| Time symptom onset -first medical contact | 76 (Q25 35-Q75 165) | – |

| Time first medical contact-activation | 25 (Q25 15-Q75 43) | – |

| Time activation-arrival in the room | 35 (Q25 24-Q75 55) | – |

| Time symptoms-balloon | 170 (Q25 120-Q75 270) | – |

| Delay first medical contact-balloon | 85 (Q25 68-Q75 111) | – |

| Delay activation-end of procedure | 76 (Q25 35-Q75 165 | – |

Times are expressed in minutes.

SD, standard deviation.

The data presented are only applicable to the network described, as the demographic characteristics, geography, hospital network, and catheterization laboratories vary for each region.4 The fact that overlap started when the catheterization team was activated instead of when the patient arrived in the room may have increased the percentage of patients reported to have a delay. However, the end time of the procedure is not always predictable and, if the activity had been concentrated in a single center, the transfer times would have been longer for 40% of the patients in the catchment area of the second center. This may have led to overlap with patients other than those indicated, greater ambulance use with a subsequent deterioration in other areas of care, and increased mortality due to delays.5 There may also have been an increase in the percentage of patients referred for fibrinolysis if the option of a second center were not available, while some of the 6 patients who experienced delay and who did not undergo PPCI may have received unnecessary fibrinolysis.

In summary, we believe that the design of regional networks should take potential demand into account and, once in operation, the percentage of patients who have experienced delays in the past year could be used as an indicator analyzed in annual steering committee meetings for the regional network.