Palpitations are a frequent reason for cardiology consultation (10%-15%).1 The AliveCor KardiaMobile recorder (AliveCor, United States) is a device linked to a smartphone application that can perform a 30-second electrocardiogram (ECG). This device has proven useful for screening for atrial fibrillation (with 92% sensitivity and 95% specificity)2; however, there are few studies on its usefulness in the management of patients with palpitations. The aim of our study was to assess the diagnostic yield of the AliveCor KardiaMobile device in unselected patients with palpitations referred to the cardiology department.

From September 2018 to October 2020, we retrospectively included consecutive patients with palpitations referred to the cardiology department with, after initial assessment, an indication for this device. Inclusion criteria were as follows: recurrent palpitations (more than 1 episode per week) lasting more than 1minute, absence of syncope, owning a compatible smartphone, and skill in using the device. We analyzed the clinical variables and ECG recordings obtained. Electrocardiographic recordings were interpreted during consultation by the cardiologist as part of routine clinical practice. Binary logistic regression was used to assess the predictors of palpitations of arrhythmic origin. A P value of <.05 was used as cutoff for statistical significance. All analyses were conducted using the SPSS v20 software package. The study was conducted according to good clinical practice guidelines and the Declaration of Helsinki and adhered to the standards of the ethics committee of our hospital.

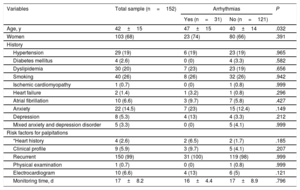

During the study period, 2109 patients attended 3300 consultations for palpitations (2549 face-to-face and 751 remote). Of these patients, the ECG recorder was used in 161 (9.4%), monitoring was performed in 96.8% (n=156), and the recorder was not used in 3.2% (n=5) due to incompatibility problems with the smartphone or a lack of skills. Of the 156 patients who used the recorder, 4 were excluded because the recording results were unavailable: thus, the final sample consisted of 152 patients. Mean age was 42±15 years and 68% were women. Median delay until beginning monitoring was 5 [2-8] days and mean monitoring time was 17±8.2 days. Most of the patients did not have heart disease and about 25% had a history of depression, anxiety, or both (table 1).

Characteristics of the sample according to electrocardiographic findings

| Variables | Total sample (n=152) | Arrhythmias | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n=31) | No (n=121) | |||

| Age, y | 42±15 | 47±15 | 40±14 | .032 |

| Women | 103 (68) | 23 (74) | 80 (66) | .391 |

| History | ||||

| Hypertension | 29 (19) | 6 (19) | 23 (19) | .965 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 4 (2.6) | 0 (0) | 4 (3.3) | .582 |

| Dyslipidemia | 30 (20) | 7 (23) | 23 (19) | .656 |

| Smoking | 40 (26) | 8 (26) | 32 (26) | .942 |

| Ischemic cardiomyopathy | 1 (0.7) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.8) | .999 |

| Heart failure | 2 (1.4) | 1 (3.2) | 1 (0.8) | .296 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 10 (6.6) | 3 (9.7) | 7 (5.8) | .427 |

| Anxiety | 22 (14.5) | 7 (23) | 15 (12.4) | .149 |

| Depression | 8 (5.3) | 4 (13) | 4 (3.3) | .212 |

| Mixed anxiety and depression disorder | 5 (3.3) | 0 (0) | 5 (4.1) | .999 |

| Risk factors for palpitations | ||||

| *Heart history | 4 (2.6) | 2 (6.5) | 2 (1.7) | .185 |

| Clinical profile | 9 (5.9) | 3 (9.7) | 5 (4.1) | .207 |

| Recurrent | 150 (99) | 31 (100) | 119 (98) | .999 |

| Physical examination | 1 (0.7) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.8) | .999 |

| Electrocardiogram | 10 (6.6) | 4 (13) | 6 (5) | .121 |

| Monitoring time, d | 17±8.2 | 16±4.4 | 17±8.9 | .796 |

Data are expressed as No. (%) or mean±standard deviation.

Heart history: family history of sudden cardiac death, ischemic heart disease, severe valvular heart disease, left or right ventricular dysfunction, significant congenital heart disease, severe pulmonary hypertension, wearing a cardiac device; clinical profile: frequent and disabling symptoms during effort; associated chest pain, syncope, or dyspnea; physical examination: organic murmur. ECG: left ventricular hypertrophy in patients younger than 50 years or without hypertension, complete right or left bundle branch block, pathological Q waves, negative T waves in precordial leads, pre-excitation, Brugada pattern, prolonged QTc (> 450ms), frequent atrial/ventricular extrasystoles.

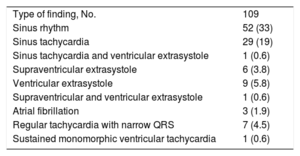

Monitoring showed that 31 patients (20%) had arrhythmias coincident with symptoms, 82 (54%) had no arrhythmias coincident with symptoms, and 39 (26%) had no symptoms during the recording period. The electrocardiographic abnormalities are shown in table 2.

Electrocardiographic findings from the ECG device linked to the smartphone application

| Type of finding, No. | 109 |

| Sinus rhythm | 52 (33) |

| Sinus tachycardia | 29 (19) |

| Sinus tachycardia and ventricular extrasystole | 1 (0.6) |

| Supraventricular extrasystole | 6 (3.8) |

| Ventricular extrasystole | 9 (5.8) |

| Supraventricular and ventricular extrasystole | 1 (0.6) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 3 (1.9) |

| Regular tachycardia with narrow QRS | 7 (4.5) |

| Sustained monomorphic ventricular tachycardia | 1 (0.6) |

Values are expressed as No. (%).

Palpitations of arrhythmic origin were more common in older than in younger patients (table 1). Age was the only independent predictor of palpitations of arrhythmic origin (odds ratio/y=1.03; 95% confidence interval, 1.01-1.06; P=.035).

Device yield was close to 75% for diagnosing patients referred to the cardiology department for palpitations who had remained undiagnosed after the initial assessment. Palpitations of arrhythmic origin were found in 20% of the patients and potentially dangerous arrhythmias were detected in 2.5%. These results differ from those reported by Reed et al.,3 who described a lower yield (55%) in patients assessed in the emergency department for palpitations or syncope, despite a longer monitoring period (90 days). Furthermore, significantly fewer palpitations of arrhythmic origin were found in their series (8.9%) than in our study. These differences may be due to the exclusion of patients with frequent palpitations or recent previous heart disease. However, Dimarco et al.4 reported a device yield of 76% in patients with low-risk palpitations who had been assessed in cardiology clinics.5 This percentage is similar to that found in the present study, although our sample included patients with palpitations with a low-risk profile and patients with risk factors. We believe our results to be of relevance, given the scarcity of data on the usefulness of this device to study the etiology of palpitations.

We also draw attention to the high percentage of patients in our study who attended for palpitations and had no arrhythmias coincident with symptoms (54%). In these types of patients, the device can be very useful as a complementary aid to diagnosis. If an arrhythmic origin is ruled out, the patient can be discharged from the cardiology department, thus avoiding repeat consultations.

This monitoring system has been validated against other traditional prolonged ECG monitoring methods and offers several advantages: convenience for patients, simplicity of use, and the ability to monitor the ECG for long periods. It also has disadvantages, such as its inability to detect asymptomatic arrhythmias or arrhythmias of such short duration that they cannot be recorded (eg, isolated and very infrequent extrasystoles).

Our study has the limitations inherent to its retrospective design. In addition, we did not record the time elapsed from the start of monitoring to event onset, and so we could not assess the minimum time needed to achieve the highest yield. Furthermore, the short monitoring period may have led to the low percentage of patients recorded as having no symptoms during the study period. Finally, the short wait between referrals from primary care to our hospital may mean that our results may not be applicable to other primary care centers with longer waits between referrals and visits to cardiology departments. The ECG recordings were interpreted by cardiologists. Thus, the results on diagnostic yield observed in this study cannot be extrapolated to other settings, such as primary care or emergency departments. Studies are needed to validate the diagnostic yield of this monitor when used by other specialists, particularly in primary care settings.

In conclusion, the AliveCor KardiaMobile cardiac monitor is simple to use and can identify the arrhythmic origin of palpitations in a high percentage of patients with palpitations.

FUNDINGNo funding declared.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONSM.E. Salar Alcaraz contributed to data collection, analysis, and interpretation, and to the writing of the manuscript. This author assumes responsibility for all aspects of the article and for investigating and resolving any questions related to the accuracy and veracity of any part of the work. F. Buendía Santiago contributed to data collection and the writing of the manuscript. P.J. Flores Blanco gave final approval to the published version. D.A. Pascual Figal critically revised the manuscript and gave final approval to the published version. A. García Alberola critically revised the manuscript and gave final approval to the published version. S. Manzano Fernández contributed to the conception and design of the study, contributed to data collection, analysis and interpretation, and the writing of the manuscript. This author critically reviewed the manuscript and gave final approval of the published version.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTNone declared.