Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) gives rise to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) leading to acute respiratory distress. In Spain, the disease has changed the way hospitals function because they have been overwhelmed by the huge number of admissions and cases of respiratory failure. This situation has required the commitment of all hospital staff, and many cardiologists have been directly involved in the care of these patients. During this task, we have become aware of the clinical impact of cardiovascular risk factors and the prevalence of previous heart disease. We launched a registry to investigate the relevance of these aspects in patients with COVID-19.

Between March 15 and April 11, 2020, we included 522 consecutive patients admitted with a diagnosis of COVID-19, which was confirmed by real-time polymerase chain reaction (rt-PCR) using nasopharyngeal samples. Respiratory failure was defined as a pO2 of less than 60mmHg on arterial-blood gas test or O2 saturation less than 90% without supplemental oxygen. All patients underwent chest X-ray, which was performed by an expert radiologist. Statistical analyses were conducted using parameters at admission.

Categorical variables are expressed as absolute frequency and percentage. Continuous variables are expressed as mean±standard deviation under the assumption of normal distribution. Groups were compared using the Student t test for continuous variables between groups and the chi-square test or Fisher exact test for categorical variables. A logistic regression model was fitted to identify factors associated with hospital mortality. A P value of less than .05 was used as a cutoff for statistical significance.

A total of 68 patients (13%) were included in the heart disease group: 42 had ischemic heart disease (30 had a history of myocardial infarction, 32 had undergone percutaneous revascularization, 3 had undergone surgical revascularization, and 4 had compatible symptoms and a positive induced ischemia test), 24 had heart valve disease (all of which were moderate or severe), and 11 had cardiomyopathy (6 dilated, 2 hypertrophic, and 3 tachycardiomyopathy). Some patients had more than 1 heart disease.

Table 1 shows the comorbidities, clinical characteristics, analytical and radiological parameters, heart rhythm on admission, and clinical evolution of patients with and without heart disease. The patients had a mean age of 68±15 years and 228 (44%) were women. Total mortality was 25% and that of patients with heart disease was 43% (29 patients; P <.001): 43% had ischemic heart disease, 37% had heart valve disease, and 64% had cardiomyopathy.

Main characteristics of the patients. comparison between patients with and without heart disease

| Total (n =522) | With heart disease (n =68) | Without heart disease (n =454) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 68±15 | 75±12 | 67±15 | <.001 |

| Women | 228 (44) | 17 (25) | 211 (47) | .001 |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Hypertension | 261 (50) | 49 (72) | 212 (47) | <.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 92 (18) | 24 (35) | 68 (15) | <.001 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 37 (7) | 8 (12) | 29 (6) | .126 |

| Dyslipidemia | 190 (37) | 45 (66) | 145 (32) | <.001 |

| Smoker | 141 (27) | 33 (51) | 108 (24) | <.001 |

| COPD | 41 (8) | 6 (9) | 35 (8) | .793 |

| Clinical parameters | ||||

| Temperature > 37.5°C | 328 (72) | 42 (76) | 286 (72) | .484 |

| SatO2 <90% | 94/467 (20) | 19/64 (30) | 75/403 (19) | .040 |

| Cough | 338 (66) | 35 (57) | 303 (68) | .077 |

| Dyspnea | 238 (47) | 33 (52) | 205 (46) | .401 |

| Diarrhea | 136 (27) | 14 (22) | 122 (28) | .324 |

| Blood test | ||||

| Leukocytes | ||||

| > 10 000/μL | 89 (17) | 15 (22) | 74 (16) | .223 |

| <4000/μL | 64 (12) | 13 (19) | 51 (11) | .059 |

| Lymphocytes <1000/μL | 253 (49) | 40 (59) | 213 (47) | .072 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase > 40 U/L | 135 (37) | 28 (51) | 127 (35) | .026 |

| Alanine aminotransferase > 40 U/L | 133 (26) | 19 (29) | 114 (26) | .535 |

| Lactate dehydrogenase > 250 U/L | 317 (63) | 45 (68) | 272 (62) | .352 |

| D-dimer> 500μg/L | 350 (71) | 51 (82) | 299 (69) | .039 |

| Creatinine > 1.5 mg/dL | 73 (14) | 14 (21) | 59 (13) | .095 |

| C-reactive protein > 10 mg/L | 453 (88) | 62 (95) | 391 (87) | .057 |

| Chest X-ray | ||||

| Abnormal | 503 (96) | 65 (96) | 438 (97) | .726 |

| Local opacity | 223 (45) | 24 (37) | 199 (47) | .168 |

| Diffuse/bilateral opacity | 290 (58) | 42 (65) | 248 (57) | .263 |

| Interstitial pattern | 86 (18) | 14 (21) | 72 (17) | .355 |

| Interstitial-alveolar pattern | 193 (39) | 22 (34) | 171 (40) | .394 |

| ECG | ||||

| Sinus rhythm | 333/376 (88) | 29/43 (67) | 304/333 (91) | <.001 |

| Specific treatment for COVID-19 | 499 (96) | 64 (94) | 435 (96) | .524 |

| Clinical evolution | ||||

| Death | 130 (25) | 29 (43) | 101 (22) | <.001 |

| Respiratory failure | 218 (44) | 43 (67) | 175 (40) | <.001 |

| Mechanical ventilation | 39 (9) | 5 (9) | 34 (9) | .903 |

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ECG, electrocardiogram; SatO2, arterial oxygen saturation.

Values are expressed as No. (%) or mean±standard deviation.

In total, 376 patients underwent an electrocardiogram (ECG), of whom 15 (4%) had a prolonged corrected QT interval, defined as more than 440 milliseconds in men and more than 460 milliseconds in women. Of the 146 without an ECG, 129 (88%) were taking at least 1 drug (lopinavir, ritonavir, hydroxychloroquine, azithromycin) that prolongs the QT interval.

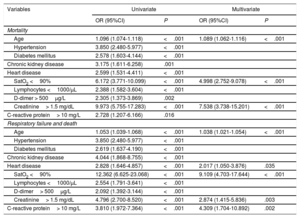

A multivariate analysis was conducted to determine the variables associated with hospital mortality and the combined event of respiratory failure in the course of the disease and mortality). The following variables were included at admission: age, hypertension (HT), diabetes, chronic kidney disease, heart disease, O2 saturation less than 90%, lymphocytes less than 1000/μL, D-dimer more than 500μg/L, creatinine more than 1.5mg/dL, and C-reactive protein more than 10mg/L. The results are shown in table 2.

Results of the univariate and multivariate analyses of mortality and the combined event of respiratory failure and death

| Variables | Univariate | Multivariate | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95%CI) | P | OR (95%CI) | P | |

| Mortality | ||||

| Age | 1.096 (1.074-1.118) | <.001 | 1.089 (1.062-1.116) | <.001 |

| Hypertension | 3.850 (2.480-5.977) | <.001 | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | 2.578 (1.603-4.144) | <.001 | ||

| Chronic kidney disease | 3.175 (1.611-6.258) | .001 | ||

| Heart disease | 2.599 (1.531-4.411) | <.001 | ||

| SatO2 <90% | 6.172 (3.771-10.099) | <.001 | 4.998 (2.752-9.078) | <.001 |

| Lymphocytes <1000/μL | 2.388 (1.582-3.604) | <.001 | ||

| D-dimer > 500μg/L | 2.305 (1.373-3.869) | .002 | ||

| Creatinine> 1.5 mg/dL | 9.973 (5.755-17.283) | <.001 | 7.538 (3.738-15.201) | <.001 |

| C-reactive protein> 10 mg/L | 2.728 (1.207-6.166) | .016 | ||

| Respiratory failure and death | ||||

| Age | 1.053 (1.039-1.068) | <.001 | 1.038 (1.021-1.054) | <.001 |

| Hypertension | 3.850 (2.480-5.977) | <.001 | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | 2.619 (1.637-4.190) | <.001 | ||

| Chronic kidney disease | 4.044 (1.868-8.755) | <.001 | ||

| Heart disease | 2.828 (1.646-4.857) | <.001 | 2.017 (1.050-3.876) | .035 |

| SatO2 <90% | 12.362 (6.625-23.068) | <.001 | 9.109 (4.703-17.644) | <.001 |

| Lymphocytes <1000/μL | 2.554 (1.791-3.641) | <.001 | ||

| D-dimer> 500μg/L | 2.092 (1.392-3.144) | <.001 | ||

| Creatinine> 1.5 mg/dL | 4.796 (2.700-8.520) | <.001 | 2.874 (1.415-5.836) | .003 |

| C-reactive protein> 10 mg/L | 3.810 (1.972-7.364) | <.001 | 4.309 (1.704-10.892) | .002 |

95%CI, 95% confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; SatO2, arterial oxygen saturation.

This study identified several relevant aspects related to COVID-19 and heart disease: a) cardiovascular risk factors (HT, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, smoking) are very common in patients with COVID-19 and, logically, more common in those with heart disease; b) patients with heart disease with COVID-19 have a more indolent clinical course, because they very often have respiratory failure and higher mortality; c) heart disease is an independent predictor of the combined event of respiratory failure and death; and d) an ECG was only performed in 72% of patients despite the use of arrhythmogenic drugs that can prolong the QT interval.

Among the cardiovascular risk factors in our patients, we highlight that the prevalence of hypertension was higher in our series than in other series. An association has previously been found between hypertension and higher mortality in this disease.1 Furthermore, the prevalence of heart disease was also higher than that recorded in other studies.2 These factors may have influenced the high mortality rate recorded in our series.

We draw attention to the lack of awareness regarding the arrhythmogenic potential of the drugs used in COVID-19 and the possibility that SARS-CoV-2 infection, as well as other coronaviruses, could give rise to arrhythmias.3 However, we emphasize that it was only during the first days of the pandemic that the majority of patients did not undergo an ECG. The percentage of patients with ECG rose to 66% in March and 85% in April (P <.001) due to the greater involvement of cardiologists during later stages and increased awareness among all staff.

The greatest limitation of this study is that troponin T and brain natriuretic peptide were not measured in most patients, because this was not stipulated in the protocol. One study found that troponin predicts mortality in patients with COVID-19 and specifically mortality in patients with heart disease.4 Furthermore, we could not assess the potential different impact of each heart disease, because the absolute number of the sample was not sufficiently large, nor could we assess the prognostic relevance of ventricular function, because it was not measured in most of the patients.

In summary, cardiovascular risk factors and heart disease are common in patients with COVID-19. Heart disease aggravates the clinical course and worsens life prognosis. The care of patients with COVID-19 has a clear cardiological dimension, thus cardiologists have to be an essential part of multidisciplinary teams in charge of their care.