The incidence of acute myocardial infarction (AMI) in elderly individuals is high.1 This population has higher rates of complications and represents a greater burden on health resources.2,3 Moreover, elderly individuals are underrepresented in clinical trials. A few randomized trials on reperfusion in elderly patients with AMI have included patients aged around 80 years,4 but extrapolation of these results to the general elderly population could be limited. Information on the impact of reperfusion on very elderly patients in everyday clinical practice is also limited.

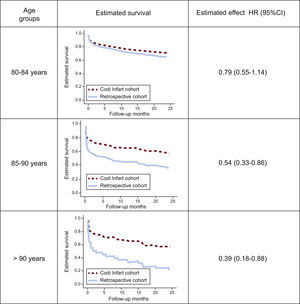

The objective of this study was to analyze the association between primary percutaneous coronary intervention and mid-term mortality in very elderly patients with AMI and ST-elevation AMI (STEMI) attended in clinical practice after implementation of a regional program (June, 2009, Codi Infart). Two cohorts were studied. The first was a retrospective cohort of consecutive patients aged 80 years or more with STEMI who were not reperfused or who underwent fibrinolysis in tertiary hospitals (between 2005 and 2009). The second was a prospective cohort of consecutive patients aged 80 years or older with STEMI who underwent primary percutaneous intervention between 2010 and 2011, drawn from the regional Codi Infart network (which covers all of Catalonia). The main baseline clinical characteristics, in-hospital outcome, and mortality during 24 months of follow-up were recorded. Mortality in the retrospective cohort was obtained by examination of the medical records. In the Codi Infart cohort, mortality registries were used. Patients in both cohorts were stratified into 3 age groups: 80 to 84 years, 85 to 90 years, and >90 years.

Quantitative variables were compared with the Mann-Whitney U test. Categoric variables were compared using the chi-square test. For analysis of the association between primary percutaneous coronary intervention and mid-term mortality, the Cox regression method was used. The models included potential confounding variables with significant association with both exposure (Codi infarct-derived cohort) and effect (mortality). Comparison of survival between the 2 cohorts was performed separately for each of the 3 age groups. The survival curves were plotted using estimates derived from the fitted model.

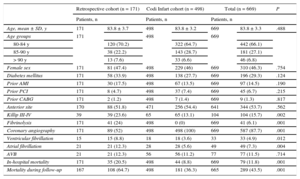

In total, 669 patients were included, 171 in the retrospective cohort and 498 in the Codi Infart cohort. The mean age was 83.9 years. No statistically significant differences in age, sex, or prevalence of the main concurrent illnesses were seen between the 2 groups: the only difference of note was a greater trend toward a higher prevalence of diabetes mellitus and prior AMI in the retrospective cohort (Table). Higher prevalences of Killip class III/IV and incidences of ventricular and atrial fibrillation during admission were observed among patients in the retrospective cohort. Mortality during both admission to hospital and follow-up was significantly greater in the retrospective cohort (median follow-up, 24 months; interquartile range, 2-24 months).

Clinical Characteristics, Management, and Outcome by Cohort

| Retrospective cohort (n = 171) | Codi Infart cohort (n = 498) | Total (n = 669) | P | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients, n | Patients, n | Patients, n | |||||

| Age, mean ± SD, y | 171 | 83.8 ± 3.7 | 498 | 83.8 ± 3.2 | 669 | 83.8 ± 3.3 | .488 |

| Age groups | 171 | 498 | 669 | ||||

| 80-84 y | 120 (70.2) | 322 (64.7) | 442 (66.1) | ||||

| 85-90 y | 38 (22.2) | 143 (28.7) | 181 (27.1) | ||||

| > 90 y | 13 (7.6) | 33 (6.6) | 46 (6.8) | ||||

| Female sex | 171 | 81 (47.4) | 498 | 229 (46) | 669 | 310 (46.3) | .754 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 171 | 58 (33.9) | 498 | 138 (27.7) | 669 | 196 (29.3) | .124 |

| Prior AMI | 171 | 30 (17.5) | 498 | 67 (13.5) | 669 | 97 (14.5) | .190 |

| Prior PCI | 171 | 8 (4.7) | 498 | 37 (7.4) | 669 | 45 (6.7) | .215 |

| Prior CABG | 171 | 2 (1.2) | 498 | 7 (1.4) | 669 | 9 (1.3) | .817 |

| Anterior site | 170 | 88 (51.8) | 471 | 256 (54.4) | 641 | 344 (53.7) | .562 |

| Killip III-IV | 39 | 39 (23.6) | 65 | 65 (13.1) | 104 | 104 (15.7) | .002 |

| Fibrinolysis | 171 | 41 (24) | 498 | 0 (0) | 669 | 41 (6.1) | .001 |

| Coronary angiography | 171 | 89 (52) | 498 | 498 (100) | 669 | 587 (87.7) | .001 |

| Ventricular fibrillation | 15 | 15 (8.8) | 18 | 18 (3.6) | 33 | 33 (4.9) | .012 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 21 | 21 (12.3) | 28 | 28 (5.6) | 49 | 49 (7.3) | .004 |

| AVB | 21 | 21 (12.3) | 56 | 56 (11.2) | 77 | 77 (11.5) | .714 |

| In-hospital mortality | 171 | 35 (20.5) | 498 | 44 (8.8) | 669 | 79 (11.8) | .001 |

| Mortality during follow-up | 167 | 108 (64.7) | 498 | 181 (36.3) | 665 | 289 (43.5) | .001 |

AMI, acute myocardial infarction; AVB, atrioventricular block; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

Unless otherwise indicated, values expressed as no. (%).

The Figure shows changes in mortality during follow-up for the 3 age groups (80-84 years, 85-90 years, and > 90 years). Patients in the Codi Infart cohort had lower mortality in all age groups; these differences were statistically significant for the 85 to 90 year and >90 year age groups.

Among the patients in the first period, those who underwent fibrinolysis had significantly lower mortality than those who were not reperfused (hazard ratio [HR], 0.48; 95% confidence interval [95%CI], 0.25-0.92; P=.026). The small size of this group (n = 41) did not allow a separate analysis by age group.

On multivariate analysis, the tertiary hospital-derived cohort was an independent predictor of mortality during follow-up (HR, 0.72; 95%CI, 0.55-0.96). The remaining predictors identified were age (HR, 1.11), female sex (HR, 0.72), diabetes mellitus (HR, 1.28), and Killip class on admission (HR, 1.88).

Therefore, the data from our study show that implementation of primary percutaneous coronary intervention was associated with a significant improvement in mortality during follow-up of elderly patients with STEMI, particularly in the case of the oldest individuals.

Our study has noteworthy limitations. Given its observational design, a selection bias for reperfusion therapy is likely, and this is likely to be particularly marked during the first period (given the clearly lower mortality within the group of patients who underwent fibrinolysis). This bias appears to be much lower during the Codi Infart period, as the data available from the IAMCAT-IV registry (a prospective registry of all STEMI in Catalonia during a 3-month period) show a low percentage (3%) of nonreperfused patients of all ages. The interesting aspect of the findings, in our opinion, is that the Codi Infart program, with a much lower selection bias, reflects a survival similar to the “best” patients from the first period (those who underwent fibrinolysis, who represented approximately 25% of the patients in the initial period). In addition, omission of relevant variables in the registry may represent a residual confounding factor. Finally, the specific causes of death and variables related to aging (frailty, functional status) would provide valuable information on the prognostic impact of the Codi Infart in this age group.

Despite these limitations, in our opinion, the data, taken from a broad cohort of elderly patients with STEMI in everyday clinical practice, indicate a decrease in mortality, particularly among the oldest patients, who have not been widely studied to date. With the progressive aging of the population, such findings are of particular importance and should be confirmed in trials designed specifically to investigate elderly patients with their particular biological characteristics.