Implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICD) are an important therapeutic option for patients with heart diseases that confer a high risk of sudden death (SD).1,2 Randomized studies have demonstrated that ICD implantation in patients with heart failure (HF) and severe ventricular dysfunction reduces mortality.

In addition, the prevalence of obesity has increased notably in recent years. Several studies have demonstrated an association between obesity and overweight and the presence of cardiovascular disease such as ischemic heart disease, HF, and SD. However, recent studies have found a paradoxically favorable prognosis for several diseases (such as HF, ischemic heart disease, atrial fibrillation, and diabetes mellitus)3–6 in patients who are overweight or obese, with lower cardiovascular hospitalization and lower total and cardiovascular mortality. However, prognosis as a function of body mass index (BMI) is unknown for patients with HF and a primary prevention ICD.

We designed a multicenter retrospective study, which was conducted in 15 Spanish hospitals with experience in the field of ICD implantation and follow-up. We enrolled 1174 patients who had received a primary prevention ICD between 2008 and 2014. Eleven patients were lost to follow-up. Only patients with a BMI measurement at the time of ICD implantation were considered; therefore, the final population was 651 patients.

In the study population, 135 individuals had a normal BMI, 283 were overweight, and 233 were obese. The baseline patient characteristics for each group are shown in the Table. The mean age was 61.70 ± 11.13 years, and 120 (18.4%) were women. The mean BMI was 28.37 (range, 18.5-55.36). Of the patients studied, 35.79% were obese, and 79.26% were obese or overweight. Patients with a higher BMI had a higher prevalence of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, and obstructive sleep apnea. No significant differences were found between BMI groups regarding treatment with lipid-lowering therapy, beta-blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, anticoagulants, aldosterone antagonists, amiodarone, and digoxin.

Demographic Characteristics

| Characteristics | BMI < 25 (n = 135) | BMI 25–30 (n = 283) | BMI ≥ 30 (n = 233) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 61 ± 11.94 | 62 ± 11.01 | 61 ± 10.80 | .374 |

| Women | 25 (18.50) | 47 (16.65) | 48 (20.60) | .508 |

| Hypertension | 72 (53.30) | 178 (62.90) | 163 (70.00) | .006 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 36 (26.70) | 77 (27.20) | 87 (37.30) | .024 |

| Dyslipidemia | 55 (40.70) | 135 (47.70) | 129 (55.40) | .022 |

| Smoking | 37 (27.40) | 81 (28.60) | 72 (30.90) | .748 |

| COPD | 11 (8.10) | 33 (11.70) | 35 (15.00) | .143 |

| OSAS | 2 (1.50) | 14 (4.90) | 20 (8.60) | .014 |

| Peripheral arterial disease | 9 (6.70) | 30 (10.60) | 17 (7.30) | .274 |

| CVE/TIA | 7 (5.20) | 27 (9.50) | 12 (5.20) | .097 |

| Cancer | 6 (4.40) | 8 (2.80) | 7 (3.00) | .663 |

| GFR by MDRD, mL/min/1.74 m2 | 76.20 ± 32.57 | 75.01 ± 23.52 | 74.11 ± 27.16 | .778 |

| LVEF, % | 26.00 [10-60] | 25.50 [10-62] | 26.27 [10-72] | .389 |

| Sinus rhythm | 108 (80.00) | 220 (77.70) | 171 (73.40) | .088 |

| AF | 42 (31.10) | 93 (32.90) | 96 (41.20) | .064 |

| Heart rate, bpm | 70 [40-133] | 67 [30-126] | 70 [35-139] | .016 |

| Ischemic heart disease | 78 (57.80) | 164 (58.00) | 121 (51.90) | .340 |

| NYHA III-IV | 56 (41.50) | 93 (32.90) | 89 (38.20) | .188 |

| QRS duration, ms | 124 [78-219] | 125 [80-210] | 120 [80-210] | .939 |

| QRS > 120 ms | 76 (56.30) | 148 (52.30) | 121 (51.90) | .578 |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 13.30 [9.00-17.80] | 13.65 [8.40-17.80] | 13.90 [9.60-17.40] | .024 |

| NT-proBNP, pg/mL | 2535 [78-21118] | 1276 [116-13 706] | 1426 [13-19 098] | .035 |

| Digoxin | 21 (15.60) | 41 (14.50) | 37 (15.90) | .901 |

| Beta-blockers | 117 (86.70) | 239 (84.50) | 206 (88.40) | .424 |

| Calcium channel blockers | 4 (3.00) | 4 (1.40) | 11 (4.70) | .085 |

| Amiodarone | 81 (60.00) | 186 (65.70) | 134 (57.50) | .147 |

| Aldosterone antagonists | 68 (50.40) | 133 (47.00) | 109 (46.80) | .771 |

| ACEI | 123 (91.10) | 249 (88.00) | 212 (91.00) | .447 |

| Statins | 81 (60.00) | 186 (65.70) | 134 (57.50) | .147 |

| Antiplatelet agents | 70 (51.90) | 151 (53.40) | 124 (53.20) | .956 |

| Anticoagulants | 38 (28.10) | 95 (33.60) | 86 (36.90) | .230 |

| Cardiovascular admission | 34 (25.20) | 70 (24.70) | 54 (23.20) | .878 |

| Inappropriate shocks | 7 (5.20) | 31 (11.00) | 22 (9.40) | .158 |

| Appropriate therapies (shocks and/or discharge) | 20 (14.81) | 53 (18.72) | 49 (21.03) | .339 |

| Electrical storm | 1 (0.70) | 12 (4.20) | 8 (3.40) | .162 |

| CRT responders | 31 (26.9) | 78 (27.8) | 81 (34.5) | .171 |

| CRT hyperresponders | 5 (3.70) | 16 (5.70) | 13 (5.50) | .680 |

| CRT nonresponders | 23 (17.2) | 29 (13.94) | 30 (12.8) | .510 |

| Mortality | 24 (17.80) | 46 (16.30) | 34 (14.60) | .713 |

ACEI, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor; AF, atrial fibrillation; BMI, body mass index; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CRT, cardiac resynchronization therapy; CVE, cerebrovascular event; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MDRD, modification of diet in renal disease; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide; NYHA, New York Heart Association functional class; OSAS, obstructive sleep apnea syndrome; TIA, transient ischemic attack.

Values are expressed as no. (%), mean ± standard deviation or mean [interquartile range].

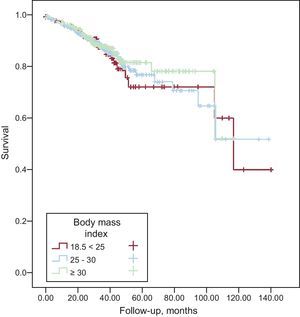

During the 8.65 ± 0.34 years of follow-up, 104 deaths (16%) were registered. Specifically, 24 patients (17.80%) with a normal BMI, 46 (16.30%) overweight patients, and 34 (14.60%) obese patients died. No differences were observed between the 3 groups regarding the number of hospital admissions. The response to cardiac resynchronization therapy was also similar between groups. No differences were found in terms of appropriate shocks, inappropriate shocks, or electrical storms. Likewise, the Kaplan-Meier survival curves showed no differences in mortality for obese and overweight patients vs normal weight patients (Figure).

The parameters shown to be predictors of mortality included age, valve disease, heart rate > 70 bpm, anemia (hemoglobin < 13 mg/dL), dyslipidemia, female sex, atrial fibrillation, left ventricular dysfunction (left ventricular ejection fraction < 25%), and renal failure (creatinine > 1.3 mg/dL). No relationship was found between BMI and mortality.

On multivariable analysis, there were no differences in mortality between the overweight and obese subgroups (overweight, hazard ratio [HR] = 0.94; 95% confidence interval [95%CI], 0.57-1.54; P = .805; obesity, HR = 0.837; 95%CI, 0.49-1.42; P = .507). Similarly, there were no differences in the number of admissions for cardiovascular causes (obesity, HR = 0.986; 95%CI, 0.547-1.468; P = .663; overweight, HR = 0.981; 95%CI, 0.611-1.575; P = .936).

The conclusion drawn from this study, based on BMI analysis, is that obesity and overweight show no prognostic differences compared with normal weight for cardiovascular mortality, cardiovascular hospitalization, and appropriate and inappropriate therapies in this population of patients with HF and an ICD implant for primary prevention of SD.

However, the interpretation of these study results should take into account the limitations of the study. First, the conclusions are drawn from BMI analysis, which does not differentiate body fat from lean body mass. Second, we did not analyze distribution of body weight (peripheral vs abdominal) or other measurements of adiposity such as body fat percentage. In addition, no information was available on the proinflammatory and nutritional status of the study population. Furthermore, the available information on BMI was taken from the time of implantation only; therefore, possible changes in this parameter at follow-up were not considered. Lastly, the retrospective design of the study increased the risk of bias.