The number of patients requiring long-term cardiology follow-up is continually increasing and traditional consultation models are unable to effectively meet demand. Accordingly, scientific societies are proposing the development of new methods that guarantee adequate coordination among the levels of care involved.1

Until 2011, our health care area relied on a traditional consultation model (25 face-to-face patient visits per day) in which referrals were not screened. In 2013, a new model was implemented: the MIVICORE model (Modelo integrado de atención primaria y cardiología: consulta virtual, cardiólogo consultor, consulta de alta resolución [integrated model of primary and cardiology care: virtual clinic, consultant cardiologist, one-stop clinic]). In this model, primary care (PC) has direct access to a cardiologist via the virtual clinic. These teleconsultations involve an electrocardiogram and are answered in 24 to 48hours with a decision regarding the need for an assessment in the one-stop clinic. In 2017, our group showed that this model reduced the number of in-person visits and delays.2

Here, we studied the impact of the MIVICORE model on the follow-up of our patients. To do so, we compared all-cause and cardiovascular death between the traditional consultation model and the MIVICORE model, as well as a composite of all-cause death, number of hospitalizations for cardiovascular reasons, and emergency department visits for cardiovascular reasons. Also evaluated was the number of in-person cardiology consultations in both groups.

Accordingly, we designed a prospective observational study that included patients with chronic heart disease: permanent atrial fibrillation, chronic coronary syndrome, heart failure with ejection fraction > 40%, and mild or moderate valvular heart disease. We excluded patients with hospitalization or interventional procedures for cardiological reasons in the preceding year, ejection fraction <40%, heart disease diagnosis within <1 year, therapy with class I and III antiarrhythmic drugs according to the Vaughan Williams classification, or estimated life expectancy <1 year. Patients in the traditional model continued to undergo in-person cardiology visits, whereas those in the MIVICORE model migrated to PC follow-up with virtual support from cardiology. Consensus protocols were developed with the new referral criteria. Follow-up was performed at 1 year for each patient.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Our Lady of Candelaria University Hospital. Informed consent was obtained from included patients.

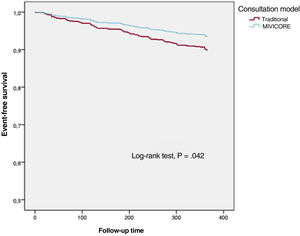

In the statistical analysis, Kaplan-Meier survival curves were calculated; they were compared using the log-rank test. A Cox proportional hazards model was adjusted with the composite of all-cause death, number of hospitalizations for cardiovascular reasons, and emergency department visits for cardiovascular reasons as the dependent variable and age, sex, hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, chronic kidney disease, and consultation model as independent variables.

Between April 2018 and April 2019, we included 1000 patients assessed in the cardiology clinics (500 patients under each model). The patients were incorporated into either of the 2 groups based on the consultation model implemented in their health center. Three patients were lost to follow-up in each group.

The MIVICORE model patients were older (71.8±11.3 vs 70.4±11.5 years; P=.042) and had a higher percentage of chronic kidney disease (30.1% vs 22.1%; P=.009). The 2 groups were homogeneous in terms of the remaining variables and cardiac treatments (table 1).

Patient characteristics at inclusion and at 1 year of follow-up under the 2 consultation models.

| Traditional (n=497) | MIVICORE (n=497) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 70.4±11.5 | 71.8±11.3 | .042 |

| Sex (male/female), n | 347/150 | 331/166 | .276 |

| Smoking | 85 (17.1) | 91 (18) | .517 |

| Hypertension | 370 (74.4) | 382 (76.8) | .375 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 175 (35.02) | 160 (32.2) | .314 |

| Dyslipidemia | 330 (66.4) | 340 (68.4) | .499 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 110 (22.1) | 150 (30.2) | .009 |

| Anemia | 72 (14.5) | 85 (17.1) | .364 |

| Stroke | 39 (7.8) | 34 (6.8) | .543 |

| Glomerular filtration rate, mL/min/1.73 m2 | 73.9 (20.6) | 69.8 (21.0) | .002 |

| Disease | .644 | ||

| Permanent atrial fibrillation | 173 (34.8) | 167 (33.6) | |

| Heart failure with LVEF > 40% | 17 (3.4) | 12 (2.40) | |

| Chronic coronary syndrome | 274 (55.1) | 278 (56) | |

| Mild or moderate valvular heart disease | 33 (6.7) | 40 (8.00) | |

| Ejection fraction, % | 60.72±6.04 | 62.04±5.54 | .297 |

| 1-y follow-up | |||

| All-cause mortality | 15 (3.02) | 14 (2.82) | .851 |

| Cardiovascular mortality | 3 (0.6) | 1 (0.2) | .598 |

| All-cause mortality, number of hospitalizations for cardiovascular reasons, and emergency department visits for cardiovascular reasons | 51 (10.26) | 33 (6.63) | .04 |

| Total number of consultations, n | 480 | 54 | <.001 |

LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction.

Unless otherwise indicated, the data represent No. (%) or mean±standard deviation.

The heart disease leading to inclusion was similar in the 2 groups; the most frequent cause was chronic coronary syndrome, followed by permanent atrial fibrillation, mild or moderate valvular heart disease, and heart failure with ejection fraction > 40%.

At the 1-year follow-up, there were no differences in all-cause death (3.02% vs 2.82%; P=.851) or cardiovascular mortality (0.6% vs 0.2%; P=.598). The patients in the traditional model showed a higher number of events of the composite of all-cause death, number of hospitalizations for cardiovascular reasons, and emergency department visits for cardiovascular reasons (10.26% vs 6.63%; P=.04). The consultation model (hazard ratio=1.752; 95% confidence interval, 1.084-2.830; P=.022) and chronic kidney disease (hazard ratio=2.697; 95% confidence interval, 1.593-4.566; P ≤ .001) were identified as predictors of the composite event. The Kaplan-Meier survival curve is shown in figure 1.

In total, 480 consultations were made under the traditional model vs 54 under the new model (P <.001). In addition, 80.7% of the patients in the traditional model made at least 1 in-person cardiology consultation; 80.04% of these consultations did not prompt diagnostic tests or therapeutic changes. Conversely, 91.3% of the MIVICORE model patients did not require an in-person cardiology consultation.

Our study shows that patients with stable chronic heart diseases can be safely followed up by PC as long as fluid communication is guaranteed with cardiology. Favorable clinical outcomes were obtained, with a decrease in the composite of death and hospitalizations, as well as a reduction in face-to-face consultations. These results should guide the search for multidisciplinary integration systems favoring appropriate continuity of care.

The present findings are in line with those published by Falces et al.3 in their study of one-stop cardiology clinics and by Comín et al.4 in their integration program involving patients with heart failure. Similarly, Rey Aldana et al.5 have reported that a program incorporating e-consultations reduces waiting times, hospitalizations, and mortality. Although multiple factors may be involved, we believe that the factors most strongly influencing these good outcomes may be the existence of shared protocols, the rapid access via the virtual platform, the minimal delay to in-person care, and the high resolution capacity. This new model generates high satisfaction for PC physicians.6

Taken together, we believe that health care systems must implement a consultation model integrated with PC that can reduce delays, in-person visits, and hospital attendance, as well as satisfy professionals.

FUNDINGThis study has not received funding.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONSAll authors contributed to the study design. R. Pimienta González, A. Quijada Fumero, and C. Hernández enrolled the patients. R. Pimienta González, E. Pérez Cánovas, and Z. Morales Rodríguez performed the data analysis. R. Pimienta González and J.S. Hernández Afonso drafted the article. All authors revised the manuscript and have given their final approval of the version submitted for publication.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTNone.