Electrical storm is a life-threatening medical emergency, characterized by 3 or more episodes of ventricular tachycardia (VT) within 24hours that are only resolved by cardioversion or defibrillation. The most effective treatment for this condition is catheter ablation, particularly in patients with myocardial scarring.1,2 However, hemodynamic instability in this clinical state leads to a higher risk of procedure-related complications and mortality. In the last few years, several studies have reported ablation procedures performed with venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (VA-ECMO) for circulatory support.3,4 This device provides hemodynamic stability and adequate organ perfusion during the procedure. In Spain, there is growing interest in the use of VA-ECMO in various clinical situations, but it is rarely applied and the published evidence to date is limited to case series.5

This study reports a retrospective analysis of patients undergoing VA-ECMO implantation in our center due to refractory electrical storm. All patients received antiarrhythmic and vasoactive drugs, deep sedation, intubation, and intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP) counterpulsation support. The interventional cardiologist performed femoro-femoral cannulation in the cardiac catheterization laboratory.

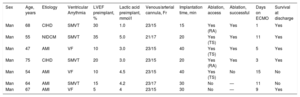

Between November 2014 and February 2017, 7 VA-ECMO were implanted in patients with electrical storm. All were men (mean age, 61.4±9 years; left ventricular ejection fraction, 17.1%±9.9%). Baseline characteristics are summarized in the Table. The etiology of the condition was ischemic heart disease in 6 patients: 4 following an acute coronary syndrome and 2 with chronic ischemic heart disease. The patients received a median of 5 shocks (range, 3-23) before ablation. The median time interval from support implantation to ablation was 2 [interquartile range, 1-4] days.

Baseline Characteristics of the Patients

| Sex | Age, years | Etiology | Ventricular Arrythmia | LVEF preimplant, % | Lactic acid preimplant, mmol/l | Venous/arterial cannula, Fr | Implantation time, min | Ablation, access | Ablation, successful | Days on ECMO | Survival at discharge |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Man | 68 | CIHD | SMVT | 30 | 1.0 | 23/15 | 15 | Yes (RA) | Yes | 1 | Yes |

| Man | 55 | NIDCM | SMVT | 35 | 5.0 | 21/17 | 20 | Yes (TS) | Yes | 11 | Yes |

| Man | 47 | AMI | VF | 10 | 3.0 | 23/15 | 40 | Yes (TS) | Yes | 5 | Yes |

| Man | 75 | CIHD | SMVT | 20 | 3.0 | 23/15 | 20 | Yes (RA) | Yes | 3 | Yes |

| Man | 54 | AMI | VF | 10 | 4.5 | 23/15 | 40 | Yes (TS) | No | 15 | No |

| Man | 64 | AMI | SMVT | 15 | 4.2 | 23/17 | 30 | No | — | 11 | No |

| Man | 67 | AMI | VF | 5 | 4 | 23/15 | 30 | No | — | 9 | Yes |

AMI, acute myocardial infarction; CIC, chronic ischemic heart disease; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; NIDCM, nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy; RA, retroaortic; SMVT, sustained monomorphic ventricular tachycardia; TS, transseptal; VF, ventricular fibrillation.

Following VA-ECMO implantation, the VT episodes remitted in 1 patient, enabling removal of the system. Electrophysiology study with ablation was carried out in 5 patients, but not in the remaining patient because of severe sepsis of respiratory origin and a state of irreversible shock.

Unfractionated heparin (aPTT, 2.5-3) was used during the procedure. A trans-septal approach was performed in 3 patients and a retroaortic approach with temporary withdrawal of IABP in the remaining 2 patients. In 4 of the 5 patients, electroanatomical reconstruction in sinus rhythm was performed with the CARTO-3 system; in the last case (Patient 4) cartography and ablation were performed in VT rhythm, facilitated by VA-ECMO hemodynamic support. The arrhythmic substrate was treated using an endocardial approach guided by the voltage map and late potentials in all patients (Patient 2 in Table 1 required a mixed endocardial-epicardial approach). With the exception of 1 case of extreme electrical instability (Patient 3), pace mapping was also carried out, with a perfect pace-map match (12/12 leads). Following ablation, clinical VT was not induced with up to 3 extra stimuli in 3 patients; nor were other VT induced. The induction protocol was not performed in Patient 3, but development of clinical VT was not observed during follow-up. Despite the procedure, electrical storm persisted in Patient 5.

The only complication related to ECMO support was a pseudoaneurysm of the femoral artery following decannulation, which was resolved by thrombin injection.

VA-ECMO was withdrawn in 5 patients following control of the arrhythmia, 1 with pharmacological treatment and 4 with effective ablation procedures. The 2 remaining patients died while receiving support, the first due to refractory electrical storm and the second due to sepsis, as previously indicated. The median duration of support was 9 days. The 5 patients who underwent VA-ECMO withdrawal were discharged with no concomitant neurological deficits (overall survival, 71.4%).

The results show that VA-ECMO can be a useful support technique for VT ablation procedures. We believe that in cases of refractory VT and concomitant cardiogenic shock, VA-ECMO support may be crucial and should be systematically evaluated.

Recent evidence regarding VA-ECMO use in refractory electrical storm4,5 and catheter ablation3 upholds its value in extremely severe cases. In our opinion, this device offers several advantages in this setting: it covers biventricular function during episodes of tachycardia,6 ensures proper oxygenation despite volume overload secondary to the use of irrigated catheters, and the exclusive positioning in the right atrium and infrarenal aortic artery does not interfere with the ablation material (in contrast to other devices, such as the TandemHeart or Impella).

Our study has the limitations inherent to a single-center retrospective analysis with a small patient cohort. Nonetheless, we believe that the favorable results obtained together with those reported in the literature should lead us to consider VA-ECMO as a component of the therapeutic arsenal for electrical storm, particularly in ablation candidates, in light of the prognostic implications of the technique when its use is effective.