Left ventricular assist devices (LVAD) have changed the prognosis of end-stage heart failure and provide a bridge to heart transplant (HT) for patients on the waiting list. Because of its cannula placement across the thoracoabdominal wall, abdominal complications may occur.

We present the case of a 58-year-old male smoker, with hypertension, type 2 diabetes, and ischemic heart disease since 1997. The implantation of a paracorporeal pulsatile LVAD (PP-LVAD) Berlin Heart Excor (BH) was decided for an end-stage ischemic cardiomyopathy, INTERMACS 3 as a bridge to HT, and univentricular BH was successfully placed without complications. Antithrombotic treatment consisted of enoxaparin, dipyridamole, and aspirin as per protocol. The patient showed repeat gastrointestinal bleeding without findings in serial endoscopies or in abdominal computed tomography, where we observed direct contact of the surrounding scar tissue of the inner cannula with the splenic flexure of the colon (Figure 1). Antithrombotic therapy was reduced during bleeding and a thrombus with high embolic risk appeared inside the external pump, which was replaced with no further complications.

After 104 days under BH support, the patient underwent transplant. The explant of the device was carried out after graft implantation during the same surgery to reduce cold ischemia time and to avoid bleeding complications, with removal of the cannula after heparin reversion. The inner cannula was difficult to remove due to intense adherence but no acute surgical complications were observed.

In the postoperative period, the patient had transient right ventricular dysfunction, treated with inotropic and vasopressor drugs. Immunosuppressive therapy consisted of basiliximab 20 mg, methylprednisolone 500 mg, and micophenolate mofetil 1000 mg for induction and methylprednisolone (0.8 mg/kg o.d.), micophenolate mofetil 1000 mg b.i.d and tacrolimus (start delayed to 14th day due to renal injury) for maintenance. Infectious prophylaxis with cefazolin, cotrimoxazole, and ganciclovir was also administered.

On the sixth day, the patient had fever and leukocytosis. Blood cultures were positive on the eighth day, demonstrating Bacteroides intestinalis and B. thetaiotaomicron bacteremia. An abdominal origin was suspected. Treatment included meropenem and anidulafungin. On the 11th day, fecaloid secretion started to drain through the wound of the inner cannula. Computed tomography confirmed the existence of ascites and an enterocutaneous fistula originating from the splenic flexure without pneumoperitoneum, so it was not connected to the peritoneal cavity (Figure 2A). Computed tomography also revealed a supradiaphragmatic collection in close contact with a retrosternal gas collection but without an identifiable relationship with the fistula, and a subhepatic collection. Iodinated contrast infusion through the fistula showed no connection between the 2 collections and the fistula. To drain the collection, obtain samples and make a differential diagnosis, the patient underwent surgical review of the mediastinum. No connection with the abdominal cavity was seen but there was Enterococcus faecium growth in the sample from the thoracic collection and in the fistula secretion. Vancomycin was added to the treatment. The enterocutaneous fistula was treated medically because there was no evidence of drainage of intestinal content to the peritoneal cavity and the surgical risk was considered unacceptable by the splachnic surgeon (because the patient was recovering from primary graft failure, acute kidney injury, and suspected mediastinal infection).

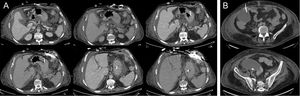

A: image of the enterocutaneous fistula from the splenic flexure of the colon, showing no connection with the peritoneal cavity or with supradiaphragmatic collection after iodinated contrast infusion through its drainage wound. B: computed tomography-guided paracentesis of the subhepatic collection.

Because of ascites progression, recurrent Bacteroides bacteremia and clinical worsening, a computed tomography-guided paracentesis was performed (Figure 2B) and 500 mL of purulent fluid were obtained from the subhepatic abscess, with E. faecium, B. thetoiotaomicron, and Butyricimonas virosa growth in cultures, and therefore tigecycline was added. Subsequently, the patient required reintubation due to ventilator-acquired pneumonia and respiratory distress. He progressed rapidly to severe sepsis and then to septic shock refractory to antibiotic treatment and vasopressor drugs. He also had acute renal failure and consumptive coagulopathy and died on the 81st day after HT.

Paracorporeal devices need cannulas crossing through the abdominal wall and some intracorporeal devices are in direct contact or placed close to the peritoneal cavity.1,2 In this setting, there is a potential for major abdominal complications. Additional factors such as anticoagulation, blood exposure to extravascular surfaces, and venous congestion attributable to right ventricular dysfunction and comorbidities, may also contribute to visceral organ complications.1 The literature on abdominal complications after paracorporeal LVAD is scarce. In a contemporary single-center series of patients with BH support, there were no abdominal complications.3 Only 1 case of small bowel fistula to the jejunum, transverse colon, and stomach during BH support4 has been published. In intracorporeal LVAD, a colonic fistula caused by a remaining inflow cannula of a HeartMate IP device in a very similar place5 has been recently reported, but abdominal complications with first-generation intracorporeal pulsatile LVADs are better known. To our knowledge, this is the first description of an enterocutaneous fistula after removal of a PP-LVAD. Surgeons should be warned that cannula withdrawal at the moment of HT can be complex because the of severe scar fibrosis. Although there was no evident connection between the fistula, the mediastinum and the rest of the abdominal collections and hematogenous dissemination cannot be excluded, the finding of Bacteroides intestinalis and E. faecium in subhepatic, peritoneal and mediastinal samples make us suspect that the fistula was the first common source of the infection soon after HT surgery, which explains the presence of retrosternal gas. Abdominal complications may be insidious after HT and must also be suspected and treated early in PP-LVAD patients, taking into account that laparotomy is usually well tolerated after HT6 and that the risk-benefit balance should be consciously measured to avoid future septic complications.