Although normal findings on exercise echocardiography (EE) are considered indicative of a good prognosis,1,2 there is little information on the prognosis of patients who have a normal EE together with positive clinical or electrocardiography (ECG) findings. Our aim was to evaluate the prognosis and angiographic results of patients in the following situations: EE (–) in the absence of positive clinical or ECG findings (negative group), EE (–) with positive clinical or ECG results (Clin/ECG group), and EE (–) with positive clinical and ECG findings (Clin+ECG group).

A retrospective analysis was performed of patients with normal EE results. Of 17 225 patients undergoing treadmill EE, those with positive findings, cardiomyopathy, moderate or severe valvular disease, or age younger than 18 years were excluded. The final population included 7127 patients with a normal first EE, defined as the absence of regional contraction abnormalities at rest and on exercise.3,4 Positive clinical findings were defined as precordial pain consistent with angina, or significant and limiting dyspnea during exercise. In patients with an assessable ECG, the test was considered positive when a horizontal or downsloping ST segment depression of ≥ 1 mm after the J point was observed in at least 1 lead, or an upsloping was seen in patients with no previous infarction.4 The ECG was considered nonassessable in patients with baseline ST abnormalities, left bundle branch block, digoxin treatment, or Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome. We evaluated major cardiac events before revascularization, defined as cardiac death or nonfatal acute myocardial infarction, as well as revascularizations during follow-up. Furthermore, we evaluated the coronary angiograms performed in the 6 months following EE testing. Coronary artery disease (CAD) was defined as ≥ 50% luminal narrowing of a main coronary artery, a major branch, or a coronary arterial or venous graft, determined visually.

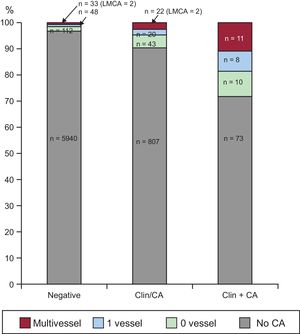

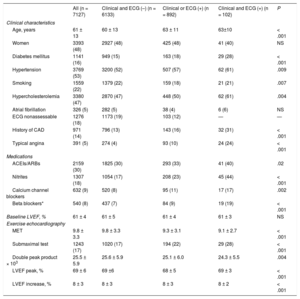

The clinical characteristics and EE results of the 3 groups of patients are shown in Table. There were 102 patients in the Clin+ECG group (1.4%), 892 in Clin/ECG (12.5%), and 6133 in the negative group (86.1%). Over a median follow-up of 2.1 [interquartile range, 0-6.7] years, there were 419 major cardiac events, with no differences between the groups (annualized major cardiac event rates, 1.2%, 1.4%, and 1.1% in groups Clin+ECG, Clin/ECG, and negative, respectively). However, the annualized revascularization rates were higher in the positive groups (9.2% Clin+ECG, 2.9% Clin/ECG, and 1.4% negative group; P < .001). Following EE testing, coronary angiography (total, 4.3%) was carried out more frequently in the positive groups (28% Clin+ECG, 9.5% Clin/ECG, and 3.1% negative group; P < .001), and the positive groups had higher percentages of angiograms showing CAD (66% Clin+ECG, 49% Clin/ECG, and 42% negative group; P < .001). Nonetheless, the rates of left main CAD and multivessel disease were very low (Figure).

Clinical Characteristics and Exercise Echocardiography Results in 7127 Patients

| All (n = 7127) | Clinical and ECG (–) (n = 6133) | Clinical or ECG (+) (n = 892) | Clinical and ECG (+) (n = 102) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical characteristics | |||||

| Age, years | 61 ± 13 | 60 ± 13 | 63 ± 11 | 63±10 | < .001 |

| Women | 3393 (48) | 2927 (48) | 425 (48) | 41 (40) | NS |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1141 (16) | 949 (15) | 163 (18) | 29 (28) | < .001 |

| Hypertension | 3769 (53) | 3200 (52) | 507 (57) | 62 (61) | .009 |

| Smoking | 1559 (22) | 1379 (22) | 159 (18) | 21 (21) | .007 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 3380 (47) | 2870 (47) | 448 (50) | 62 (61) | .004 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 326 (5) | 282 (5) | 38 (4) | 6 (6) | NS |

| ECG nonassessable | 1276 (18) | 1173 (19) | 103 (12) | — | — |

| History of CAD | 971 (14) | 796 (13) | 143 (16) | 32 (31) | < .001 |

| Typical angina | 391 (5) | 274 (4) | 93 (10) | 24 (24) | < .001 |

| Medications | |||||

| ACEIs/ARBs | 2159 (30) | 1825 (30) | 293 (33) | 41 (40) | .02 |

| Nitrites | 1307 (18) | 1054 (17) | 208 (23) | 45 (44) | < .001 |

| Calcium channel blockers | 632 (9) | 520 (8) | 95 (11) | 17 (17) | .002 |

| Beta blockers* | 540 (8) | 437 (7) | 84 (9) | 19 (19) | < .001 |

| Baseline LVEF, % | 61 ± 4 | 61 ± 5 | 61 ± 4 | 61 ± 3 | NS |

| Exercise echocardiography | |||||

| MET | 9.8 ± 3.3 | 9.8 ± 3.3 | 9.3 ± 3.1 | 9.1 ± 2.7 | < .001 |

| Submaximal test | 1243 (17) | 1020 (17) | 194 (22) | 29 (28) | < .001 |

| Double peak product × 103 | 25.5 ± 5.9 | 25.6 ± 5.9 | 25.1 ± 6.0 | 24.3 ± 5.5 | .004 |

| LVEF peak, % | 69 ± 6 | 69 ±6 | 68 ± 5 | 69 ± 3 | < .001 |

| LVEF increase, % | 8 ± 3 | 8 ± 3 | 8 ± 3 | 8 ± 2 | < .001 |

ACEIs, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors; ARBs angiotensin II receptor blockers; CAD, coronary arterial disease; ECG, electrocardiogram; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MET, metabolic equivalents; NS, not significant.

The values express n (%) or mean ± standard deviation.

The results of this study support the notion that a negative EE has excellent prognostic value.1,2 Of note, when each component evaluated was normal (absence of clinical findings, and negative ECG and EE), even the revascularization requirement was minimal. Some patients with positive clinical and ECG findings had CAD, but it was usually single-vessel disease and the affected territories that were not dependent on the left anterior descending artery. This is because EE is very sensitive for detecting multivessel disease and left anterior descending artery disease but is not as sensitive for single-vessel disease or disease affecting the right coronary or circumflex arteries. In a recent study performed in EE (–) patients, a positive ECG was not associated with a larger number of events or revascularizations,5 although the results might have been different if patients had been positive both clinically and on ECG. Thus, although events do not seem to be associated with positive status other than image-related, this group may benefit from coronary revascularization. For patients who are less likely to benefit from coronary angiography and eventual revascularization, such as those showing only clinical or only ECG findings, coronary computed tomography examination could be considered,6 since “blank” coronary angiograms were not uncommon in this subgroup.