We recently treated a patient with infective endocarditis (IE), and there was some controversy about the indication and risk of performing a colonoscopy examination.

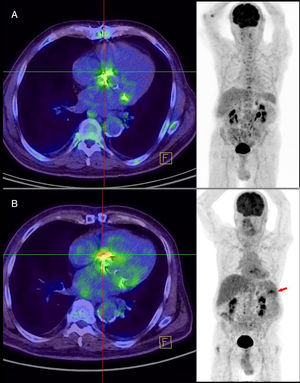

An 82-year-old man with a history of hypertension and a biological prosthetic aortic valve implanted 4 years previously was seen for a 2-day history of fever (39°C) with no focal infectious source. He had not undergone dental treatment recently. On physical examination, several teeth were found to be in poor condition and a systolic murmur was detected at the left sternal border. There was no atrioventricular block on electrocardiography, and the analyses showed mild anemia (12.7 g/dL). Chest radiographs were normal. The initial transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) study showed no relevant abnormalities. Penicillin-susceptible Streptococcus agalactiae isolates were recovered from blood culture of all 4 vials obtained. A new TEE performed on the eighth day after hospitalization depicted 2 vegetations, 3 and 8mm in size, on the prosthetic aortic valve (Figure 1). After the first TEE, 18F-FDG positron emission tomography combined with computed tomography (PET/CT) had shown mild homogeneous uptake that did not suggest IE (Figure 2), although the patient already fulfilled some of the IE criteria (1 major and 3 minor).

Ceftriaxone 2g/24h was prescribed for 6 weeks and gentamicin 180 mg/24 h for the first 2 weeks, both given intravenously. Oral amoxicillin 1 g/6 h was then given for 2 additional weeks to treat left facet joint arthritis at L3-L4. Colonoscopy was performed in the fifth week of ceftriaxone treatment, and a 2-mm colon polyp was resected (tubular adenoma). The patient showed fever at 12 hours following this procedure. Four days after completion of antibiotic treatment, new blood cultures were obtained and Enterococcus faecium was isolated from the 4 vials. The patient had experienced low-grade fever over the past 7 days. The physical examination findings were unremarkable. Laboratory analyses showed worsening of the anemia (hemoglobin, 10.6g/dL) and a C-reactive protein increase of 106mg/dL (0.1-10mg/dL). There were no signs indicative of IE on TEE examination. PET/CT depicted intense, irregular uptake at the prosthetic aortic valve, highly suspicious of IE (Figure 2) and a hypometabolic splenic lesion with peripheral uptake, approximately 6 × 4cm in size, indicating a septic embolism. As the microorganism was resistant to ampicillin and gentamicin, the patient was treated with daptomycin 700 mg/24 h and fosfomycin 2 g/6 h for 6 weeks. The patient's clinical course was favorable and follow-up blood cultures were sterile.

This case prompted a 2-fold reflection: first, on how intensive the search should be for a possible infectious source in suspected IE, and second, on whether IE prevention measures should be taken in patients undergoing colonoscopy. Although European guidelines recommend colonoscopy only in cases of IE due to Streptococcus gallolyticus,1 some authors believe a more intense search for the probable infectious source (including colonoscopy) is advisable in patients older than 50 years.2 Considering our patient's age and the possible intestinal origin of the infection (S. agalactiae), we decided to carry out colonoscopy while completing the antibiotic therapy. The scant relationship between S. agalactiae IE and the risk of colon cancer reported in the literature could justify omission of colonoscopy. Of particular note in the case reported was the development of a second IE episode due to a different microorganism (E. faecium). The prolonged ceftriaxone administration may have enhanced colonic proliferation of E. faecium, and colonoscopy may have led to an episode of bloodstream infection. Nonetheless, a recent review3 found only 25 cases of IE attributable to endoscopic procedures, which supports the current recommendation to refrain from prophylactic antibiotic administration in patients undergoing such procedures.1 The microorganisms most commonly implicated in these cases are enterococci and viridans streptococci.4 To our knowledge, this is the first case of enterococcal IE occurring in a patient who underwent colonoscopy while receiving IE treatment. The bacterial strain causing the second episode was resistant to amoxicillin (the recommended antibiotic in the former indication). Of note, recent changes in antibiotic prophylaxis guidelines in western countries have led to substantial reductions in the number of patients for whom prophylaxis is recommended. In parallel, it has been reported that the incidence of IE may be increasing significantly since the introduction of these new recommendations.5 Based on all of the above considerations, we believe that although the risk of IE is low in patients undergoing colonoscopy, prophylaxis may be justified in certain subgroups at a high risk.

.