Idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) has a genetic cause in up to 20% of cases.1 Familial clinical screening reveals that 20%-48% of probands have affected relatives, consistent with a diagnosis of familial DCM.1,2

Barth syndrome is an X-linked recessive disorder caused by tafazzin (TAZ) gene mutations.3 It is characterized by DCM, neutropenia and 3-methylglutaconic aciduria4 and the life expectancy is limited during early infancy.

We report on the clinical course of a 30-year-old male with Barth syndrome and the results of genetic study of the TAZ gene in his relatives. To evaluate the implication of TAZ gene in the etiology of DCM and left ventricular non-compaction we studied the TAZ gene in 48 DCM and left ventricular non-compaction patients.

Our patient was first evaluated for respiratory infection in the pediatric department when he was 10 months old. Cardiomegaly, systolic dysfunction, and myopathy were diagnosed at that time. Patient developmental milestones were normal. Infancy was complicated with frequent infections. At 20 years of age, his main complaints were fatigue and muscular claudication. His weight was 71kg and his height 180cm.

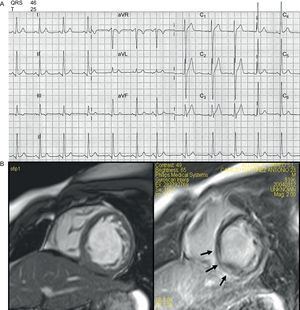

Cardiologically, he had never experienced syncope and presented with occasional episodes of chest pain and palpitations. A recent electrocardiogram (ECG) was essentially unremarkable (Fig. 1A), showing in sinus rhythm a slightly short PR interval (0.12 ms), and mildly high voltage QRS, in particular deep S waves in V1-V2 with ST elevation with an early repolarization pattern. QRS and QT intervals were normal. Repeated 24-h and 7 day ambulatory Holters had failed to find any arrhythmia apart from sinus tachycardia. His exercise capacity was measured on the treadmill, where he was able to exercise for only 4min. The heart rate during the test went from 78 bpm to 188 bpm (96% of predicted), with a peak VO2 achieved of 13.3 mL/kg/min. The test was stopped because of dyspnea. There were no ST-T changes and no arrhythmias during the cardiopulmonary test. A low dose of beta blockers was then added to chronic therapy with losartan with good tolerance and symptoms benefit.

A recent echocardiogram demonstrated mild left ventricular systolic impairment (ejection fraction was 50%) with normal end-diastolic dimension (50 mm). Magnetic resonance confirmed echocardiographic findings and showed hypertrabeculated mid and apical segments of the left ventricle meeting criteria for non-compaction. There was a line of gadolinium enhancement at the inferior-posterior wall (mid myocardium) (Fig. 1B).

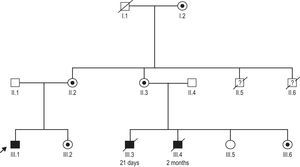

Family history was remarkable for 2 male cousins who died because of heart failure (at 1 month and 2 months old) and 2 male uncles who also died in early infancy due to suspected infectious disease (Fig. 2). Hematologic and metabolic studies revealed that the patient had neutropenia, lactic acidemia, and 3-methylglutaconic aciduria; the diagnosis of Barth syndrome was suspected.

A mutation c.280C>T (R94C)6 in the TAZ gene was identified in our patient (III.1) (Fig. 2). This change was also present in the 2-month-old male cousin who died of heart failure (III.6). Samples from the other suspected affected male relatives were not available. Our patient¿s mother (II.2), aunt (II.3), sister (III.2), and grandmother (I.2) were all carriers of the mutation. All female carriers were evaluated and had normal cardiac examinations. The clinical spectrum in carriers of this mutation is broad; the genotype-phenotype relationship is incompletely understood with 4 infant males dying in this family from either heart failure or infectious disease. Some additional genetic or environmental factors may have played a role in the unusual course of the disease in our index patient.

Of 48 consecutive pediatric (n=17; age, range 2 days-14 years; 12 males) and adult (n=31; age, range 15-72 years; 24 males) patients with idiopathic DCM and/or left ventricular non-compaction were also evaluated. Mean left ventricular ejection fraction was 41.6%±19.7%. Twenty-two had left ventricular non-compaction (11 isolated left ventricular non-compaction). Seven were in NYHA class IV, 8 in class III, and 11 in NYHA II. There were 3 heart transplants in this group. The genetic study in these patients has failed to demonstrate mutations in the TAZ gene.

There is only one other similar adult Barth syndrome case (35 years old), reported by Kelley et al. (1991).5 Repeated holters have failed to demonstrate any arrhythmia or conduction disease in our patient. Genetic diagnosis is essential for genetic counseling in this X-linked genetic disorder. Early and accurate diagnosis can help medical treatment and improve prognosis.

Despite poor prognosis of Barth syndrome during infancy, patients can survive until adulthood. We have not found TAZ gene mutations in our cohort of pediatric and adult patients with isolated DCM or left ventricular non-compaction, and therefore Barth¿s syndrome should be suspected in family histories with men who died early by DCM and in adult males with characteristic clinic data, as our case indicates that survival is possible.

FundingThis study has been funded by a research grant from the Fundación Española del Corazón-Spanish Society of Cardiology 2007 and by the Red de Investigación Cardiovascular (RECAVA).

.