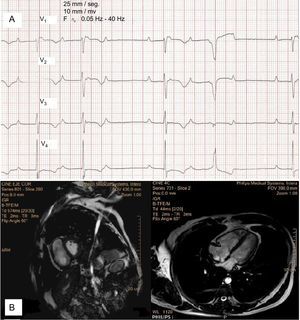

Arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia (ARVD) has a prevalence in the general population of 1:2500 to 1:5000. Sudden death is the first manifestation of the disease in 11% to 22% of patients.1 We present the case of a 58-year-old man, with no personal or family history of heart disease, who was admitted to our hospital with a 1-month history of dyspnea. The electrocardiogram showed sinus rhythm with second-degree atrioventricular block Mobitz I, narrow QRS with RR’ pattern and epsilon wave in V1, inverted T waves from V1 to V4, and isolated ventricular ectopic beats with complete left bundle branch block (Figure 1A). Magnetic resonance imaging showed 31% ejection fraction of the right ventricle (RV), with ventricular volume in the upper limit of normal (end-diastolic volume indexed to body surface area, 92 mL/m2), which was greater than the left ventricular volume (end-diastolic volume indexed to body surface area, 72 mL/m2), with interventricular septum shift to the left due to volume overload in the right chambers (Figure 1B). We also observed dyskinesia, fibrosis and aneurysmal dilatation on the RV outflow tract and inferior wall. This combination of findings enabled us to confirm a diagnosis of ARVD.1 In view of the patient's symptomatic atrioventricular block, a permanent pacemaker was indicated. We finally decided to insert an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD), due to intermediate risk of sudden death. During admission, telemetry showed no arrhythmia episodes. The patient was asymptomatic on discharge and genetic testing found no mutations associated with ARVD. One month later, the patient returned to our clinic to report an ICD discharge. The electrograms showed regular occurrence of atrial tachyarrhythmia, not previously observed, electrically-stimulated ventricular rhythm most of the time and several episodes of sustained ventricular tachycardia (SVT), all interrupted with antitachycardia pacing except 1, which received an ICD shock (Figure 2). Immediately before each SVT episode, we observed that the atrial arrhythmia did not reach the ventricle (appropriate mode switch), followed by detection of a ventricular beat, and then the SVT preceded by a paced ventricular beat. The patient was prescribed amiodarone, beta-blockers and anticoagulation therapy. Electroanatomic mapping in the electrophysiological study showed extensive areas of endocardial scarring on the RV inflow tract, basal portion of the inferior wall, and outflow tract. After receiving substrate ablation, the patient was discharged. He remains asymptomatic after 12 months of follow-up.

A: Electrocardiogram showing sinus rhythm with second-degree atrioventricular block Mobitz I, epsilon wave, inverted T waves from V1 to V4, and isolated ventricular ectopic beats with complete left bundle branch block. B: short axis and 4-chamber views of cardiac magnetic resonance imaging showing greater right ventricular volume than left ventricular volume and interventricular septum shift to the left.

Arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia is an autosomal-dominant disease that mainly affects genes responsible for cell-to-cell binding (plakoglobin or desmoplakin). The pathogenic hypothesis suggests that cell death occurs as a result of variations in the desmosomes, with fibrofatty tissue replacement of the myocardium, creating a substrate for ventricular arrhythmias. These changes take place predominantly in the RV, although the left ventricle may also be affected.1 Clinical symptoms are usually seen in adolescence and adulthood, although some individuals may remain asymptomatic. The first manifestation may be sudden death or progressive heart failure due to contractile dysfunction. In advanced disease stages, biventricular dilatation may resemble dilated cardiomyopathy. The diagnosis is based on the presence of several validated criteria. Patients require individualized treatment.2

Fibrofatty infiltration of the bundle of His has been found in pathology studies in more than 60% of patients with ARVD,3 but this histologic evidence does not correlate with conduction abnormalities. Few cases of ARVD with conduction abnormalities have been described in the literature.4,5 Peters et al.6 studied the electrocardiograms of 376 patients with ARVD and found conduction abnormalities (including complete right bundle branch block and any degree of atrioventricular block) in only 6% of patients. Our case presentation is interesting for 2 reasons: first, because of its rare presentation and second, because of the patient's history of life-threatening arrhythmias. Fortunately, these arrhythmias began only after ICD implantation, which was not clearly indicated in our patient according to his initial manifestations. Although we cannot completely rule out the ICD ventricular discharges as a trigger of the arrhythmias, atrial tachyarrhythmia may play a role in the onset of the SVT episodes because of the new source of ventricular activation (discharges instead of conduction) in a patient with an arrhythmogenic substrate and heart disease.

A consensus statement has recently been published for the treatment of ARVD and it includes an algorithm to identify patients who will derive the greatest benefit from ICD implantation. Patients at high risk are well identified but those at intermediate risk, such as our patient, are poorly identified. This stratification highlights the importance of individualizing the management of patients with ARVD and the indication for ICD implantation.