Infections were the main cause of death between the first month and the first year after transplant in the 250 patients who underwent heart transplantation in 2014 in Spain (36.6% of deaths).1 The incidence of fungal infections has increased due to the more widespread use of immunosuppressants. These infections account for a high proportion of the morbidity and mortality in heart transplant recipients, despite the effectiveness of new treatments.2

Fungal pleural empyema is a rare condition that, despite an associated mortality greater than 70%, is not included in the classification of Aspergillus-related pulmonary diseases. The most common mechanism by which the fungus reaches the pleural cavity is rupture of an aspergilloma cavity or complication of pre-existing chronic empyema. We present 2 cases of fungal pleural empyema in heart transplant recipients between October and December 2015 in our hospital.

The first case is a 65-year-old man who was placed on the heart transplant waiting list because of dilated idiopathic cardiomyopathy with advanced heart failure. After 3 months on the waiting list, he was admitted in a state of cardiogenic shock requiring implantation of percutaneous ventricular assist device (Impella CP) and emergency heart transplant. Serology (cytomegalovirus, syphilis, hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus, human immunodeficiency virus, herpes zoster virus, and Toxoplasma) and the Mantoux test were negative before transplant. Myocardial biopsy during follow-up did not reveal any findings indicative of acute cellular rejection. On day 34 after transplant, asymptomatic right pleural effusion was detected. Chest drainage was performed, with 850mL of purulent and malodorous liquid collected. Broad-spectrum antibiotic treatment (meropenem and linezolid) was started and urokinase was administered intrapleurally. Prophylactic treatment was maintained (trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, valganciclovir), along with immunosuppression with mycophenolate mofetil, prednisone, and tacrolimus. Culture of pleural empyema detected growth of more than 103 colony-forming units of Aspergillus fumigatus, and voriconazole monotherapy was started on post-transplant day 39. Aspergillus, Pneumocystis, Mycobacterium tuberculosis and galactomannan were not detected by polymerase chain reaction of bronchioloalveolar lavage. The patient completed 2 months of treatment with voriconazole (with measurement of tacrolimus concentrations every 2 weeks) and prophylaxis continued with inhaled amphotericin B, with good clinical and radiological outcomes.

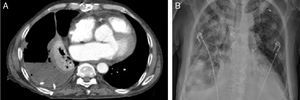

The second patient was a 63-year-old man with a diagnosis of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in dilated phase and advanced heart failure who was admitted in a state of cardiogenic shock requiring inotropic drugs and intra-aortic balloon counterpulsation. After requesting an emergency transplant, he underwent heart transplant. Serology and the Mantoux test before transplant were negative. A month and a half after heart transplant (day 50), he showed symptomatic cytomegalovirus infection (the first infection with this virus), requiring intravenous ganciclovir treatment. He developed severe pancytopenia that required discontinuation of mycophenolate mofetil and tacrolimus dose reduction. After 3 months, his clinical status deteriorated, and severe ventricular dysfunction was detected. An endomyocardial biopsy showed acute humoral rejection. He received treatment with methylprednisolone, plasmapheresis, gammaglobulins, and rituximab, and immunosuppressive therapy was adjusted. A follow-up chest X-ray performed on post-transplant day 123 revealed right pleural effusion. He had low-grade fever. Empirical antibiotic therapy was initiated. In view of his deteriorating condition and suspected opportunistic infection (Figure), the intensity of the antibiotic therapy was increased in the following 48hours (piperacillin-tazobactam and linezolid). Flexible fiberoptic bronchoscopy was performed; no endobronchial abnormalities were detected but polymerase chain reaction was positive for Aspergillus. Biochemical analysis of the pleural effusion was consistent with empyema, and a growth of Aspergillus fumigatus was isolated. Treatment was initiated with intravenous voriconazole on day 137 after transplant. Despite these pharmacological measures, the patient died after 12 days of treatment.

Treatment of fungal empyema is not often required and there is no standard approach due to the variable penetrance of systemic antifungals in the pleura; combinations of 1, 2 or 3 drugs are used (voriconazole, amphotericin B, and echinocandin).4,5 Current recommendations indicate immediate antifungal monotherapy after isolation of Aspergillus fumigatus in immunosuppressed patients. Antifungal combinations are reserved for cases of therapeutic failure. In these cases, a personalized approach is necessary.5

Pharmacological prophylaxis against fungal infections in recipients of solid organ transplants, such as heart transplants, is not general practice, but recent guidelines recommend considering fungal prophylaxis with echinocandins, voriconazole, or amphotericin B in patients considered at high risk (those undergoing hemodialysis, post-transplant surgical procedures, environmental colonization by Aspergillus, or documented prior cytomegalovirus infection).3 Clinical suspicion and early treatment initiation are associated with lower mortality, but long-term therapy is often required and, at times, surgical resection is performed.

It is essential to conduct an individualized benefit-risk assessment. Clinicians should be aware at an early stage of the possibility of opportunistic infections and adjust accordingly the therapeutic algorithms in each hospital to individual risk factors (obesity, prior diagnosis of diabetes mellitus, repeat intervention for bleeding conditions, and the results of epidemiological surveillance).6 In our center, monthly epidemiological surveillance is undertaken in areas of surgery related to the heart surgery department. There were no findings during the aforementioned period. Nevertheless, after isolation of Aspergillus fumigatus in 4 patients who underwent heart transplant (2 cases of parenchymal involvement and 2 of pleural empyema), we decided to return to universal prophylaxis for the first 6 post-transplant months with weekly inhaled amphotericin B. This drug was chosen because of its weaker interactions with immunosuppressants. After these first 6 months, treatment is individualized for each patient.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTL.H. Varela Falcón holds a grant from the Fundación Carolina-BBVA.