A 52-year-old woman was admitted with right ventricular, inferior-posterior wall acute myocardial infarction, Killip class IV. She had a history of active smoking, hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, HIV infection on treatment with darunavir and ritonavir, and depressive syndrome treated with citalopram.

She rang the emergency services at 1:15 AM with chest pain that had started at 6:30 PM, and was found to have a blood pressure of 61/30mmHg, complete atrioventricular block at 20 bpm, narrow QRS interval and ST elevation in inferior and right leads (5 mm), and reciprocal changes in V2-V3. At home, the patient was started on an adrenaline intravenous infusion (0.08 mg/h) and was given aspirin 250 mg and unfractionated heparin 4200 IU, both intravenously, and clopidogrel 600 mg orally. She was then transferred to the cardiac catheterization unit at 3:35 AM.

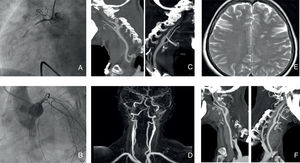

The adrenaline infusion was discontinued. A transfemoral pacing catheter was deployed and coronary angiography was performed via a femoral approach (due to radial vasospasm), showing acute occlusion of the proximal right coronary artery (Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction [TIMI] 0, Rentrop 0) (Figure A) and severe vasospasm of the left anterior descending artery (Figure B). A thrombectomy was performed with metal stent implantation. The final TIMI score and blush grade were both 3 at 4:29 AM.

A and B: occlusion of the proximal right coronary artery and vasospasm of the left anterior descending artery in the coronary angiogram. C and D: severe bilateral stenosis of the extracranial internal carotid arteries in the computed tomography angiogram and magnetic resonance angiogram. E: Multiterritorial cerebral infarctions in the brain magnetic resonance imaging. F: normal lumen of the bilateral internal carotid arteries.

Dobutamine and noradrenaline were then administered for 24 hours postintervention. The pacing catheter was withdrawn 48 hours later. Echocardiography showed moderately depressed biventricular systolic function (left ventricular ejection fraction 35%; tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion [TAPSE] 11 mm) and inferior wall akinesis. The findings were confirmed by cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

Despite making good clinical progress, the patient had 2 transient episodes of facial and right arm paresis with motor aphasia, at 72hours and 96hours postadmission. Computed tomography showed only severe bilateral stenosis of the extracranial cervical segments of the internal carotid artery. Both arteries were patent (Figure C). These findings were confirmed on carotid Doppler ultrasound and magnetic resonance angiography (Figure D). Carotid dissection and aortic arteritis were ruled out. In the brain MRI we found unexpected multiple subacute ischemic infarcts in different territories (predominantly in the left hemisphere) of possible embolic cause (Figure E) and we therefore prescribed oral anticoagulants. Transesophageal echocardiography showed a complicated atherosclerotic plaque without mobile components in the aortic arch, but no evidence of intraventricular thrombus or patent foramen ovale. The patient had no observed episodes of supraventricular arrhythmias during admission.

She had no further neurological events and 72 hours after starting the calcium antagonists, computed tomography angiography (Figure F) and carotid Doppler ultrasound showed normal lumen of the internal carotid and left anterior descending arteries. We ruled out vasospasm and vasculitis by testing for inflammatory markers, thyroid hormones, metanephrines, autoantibodies and serology, as well as cocaine use.

The final clinical outcome was satisfactory and, at discharge, the patient was prescribed triple antithrombotic therapy with acenocoumarol, aspirin, and clopidogrel. We switched her antiretroviral treatment to tenofovir/emtricitabine and dolutegravir to avoid drug interactions. At a 6-month follow-up, transesophageal echocardiography showed no aortic plaque changes and clopidogrel was discontinued. One year later, the patient was in New York Heart Association functional class II, without angina and with recovered biventricular systolic function (left ventricular ejection fraction, 57%; TAPSE, 17 mm). The only reported neurological sequela was mild paresthesia in the right hand.

The coexistence of a coronary thrombotic event, multiple cerebral embolic events, and generalized vasospasm phenomena, as described here, is rare in the literature.

Sympathomimetic drugs, such as adrenaline, cause vasospasm, but this adverse effect is not seen in all patients. In our case, the vasoconstriction may have been exacerbated by various factors, including HIV infection, ritonavir therapy and smoking, which is a potent coronary and carotid vasoconstrictor. Cases have also been described of cerebral vasospasm caused by serotonin reuptake inhibitors, such as citalopram.1

In addition, Yoshimoto et al.2 described the association of carotid and coronary vasospasm, coining the syndrome “idiopathic carotid and coronary vasospasm”. Two cases have been reported, also associated with myocardial and cerebral infarctions, and they even required carotid stent deployment.3

Therefore, our initial hypothesis regarding the neurological symptoms was adrenaline-induced cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome in a patient in cardiogenic shock and multiple predisposing risk factors. However, the brain MRI revealed a possible embolic cause, which was indeed compatible with the patient's symptoms. We therefore considered the possibility that the bilateral vasospasm was a radiological finding without clinical significance. We searched for the embolic source and found only 1 complicated atherosclerotic plaque without mobile components in the aortic arch, which could have been explained by HIV-related aortic inflammation.4 We were surprised that the plaque remained unchanged after 6 months of triple antithrombotic therapy. The embolic source is therefore still unknown, although we cannot rule out the presence of an intraventricular thrombus during the hyperacute phase of the infarction, due to the extensive akinesia and ventricular dysfunction. Although a stroke more than 48hours after a coronary angiogram is rare, another possibility is an embolism from the aortic plaque caused by catheter trauma.5

In conclusion, we report an extremely rare case of concomitant thrombotic and embolic phenomena, and multiterritorial vasospasm. Our case reflects the complexity of the differential diagnosis in stroke after myocardial infarction. The diagnosis requires multiple imaging techniques, a multidisciplinary approach, and complex antithrombotic therapy management.