To the Editor,

Postpartum hemorrhage is a cause of maternal deaths and morbid events in western countries, due to uterine atony in the majority of cases. In addition to monitoring, resuscitation, and transfusion procedures, the management of post-partum hemorrhage generally follows a stepwise protocol in international guidelines. The first step consists of the administration of oxytocin or ergometrin. If bleeding persists, then prostaglandins (sulprostone, carboprost and misoprostol) are usually recommended.

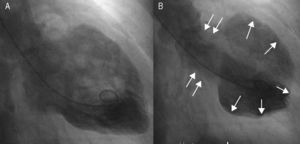

A 50-year-old pregnant woman was admitted to our hospital at 28 weeks gestation for an elective cesarean delivery. Her medical history included only obesity. During the fifth month of pregnancy, she had a screening transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) which showed preserved systolic and diastolic functions without valvular disease. Cesarean delivery was performed following the administration of standard spinal anesthesia without hemodynamic instability. After delivery, 30 UI of oxytocin were administrated to treat uterine atony associated with postpartum hemorrhage. A few minutes later, she experienced chest pain and palpitations. Electrocardiography (ECG) showed a junctional tachycardia with narrow QRS complex, retrograde P waves, and significant diffuse ST-segment depression (Figure 1). The supraventricular tachycardia spontaneously resolved without occurrence of heart failure. Four hours later, as uterine atony and bleeding continued, she received 1.5mg sulprostone over 3h with a stable infusion rate of 0.5mg/h. Thirty minutes before the end of infusion, she became hypertensive (220/110mmHg) and tachycardic (130bpm). She also complained of sudden chest pain and shortness of breath. Her oxygen saturation fell to 85% percent and lung crackles appeared, leading to the diagnosis of hypertensive pulmonary edema. She was rapidly treated with reservoir face-mask oxygen, intravenous nitrates, and diuretics. ECG showed only a sinus tachycardia without T-wave or ST-segment abnormalities. Chest radiography confirmed pulmonary edema. In addition, she had elevated cardiac enzyme 6h later (troponin I 3.5μg/L, normal range < 0.2μg/L). She was admitted to the cardiology intensive care unit. The initial TTE revealed a severe left ventricular (LV) systolic dysfunction (left ventricular ejection fraction [LVEF] estimated at 35%) due to an extensive apical and midventricular akinesis contrasting with hypercontraction of the basal segments. Moreover, a small pericardial effusion was noted. Eighteen hours after the onset of heart failure symptoms, coronary angiography ruled out obstructive coronary disease and there was no angiographic evidence of acute plaque rupture. Ventriculography showed the same LV wall motion abnormalities as TTE (Figure 2). The diagnosis of tako-tsubo cardiomyopathy (TTC) was considered and acute heart failure treatment continued with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and beta-blockers. She made good clinical progress and was discharged from the intensive care unit at day 4. The follow-up TTE, 5 days after discharge, showed a total recovery of LVEF and the ECG indicated sinus rhythm without T-wave or ST-segment abnormalities.

Figure 1. Twelve-lead electrocardiogram demonstrating junctional tachycardia with retrograde P waves (arrows) and diffuse ST-segment depression.

Figure 2. Left ventriculography (right anterior oblique 30°) showing apical ballooning. A, diastole; B, systole.

Diagnosis criteria of TTC are: a) transient hypokinesis, akinesis, or dyskinesis in the LV mid-segments with or without apical involvement1 and frequently, but not always, a stressful trigger event2; b) the absence of obstructive coronary artery disease or angiographic evidence of acute plaque rupture; c) new ECG abnormalities or modest elevation in cardiac troponin, and d) the absence of pheochromocytoma and myocarditis.3 Hormonal disturbances secondary to excessively elevated serum catecholamine levels have been suggested to be the cornerstone of the transient LV apical dysfunction. Other possible mechanisms like coronary vasospasm, coronary microcirculation alterations, or generation of a transient intraventricular dynamic gradient have also been proposed. A recent literature review found 6 published cases of TTC after cesarean delivery.4 In 4 cases, the onset of symptoms was preceded by administration of vasoconstrictive substances, including adrenergic stimulants (adrenaline, phenylephrine, ergovonine, and ephedrine) and anticholinergics (atropine). Our case report presented a similar pattern, as sulprostone is also a vasoconstrive substance that elevates plasma levels of noradrenaline.5 To our knowledge, we described the first case of TTC after intravenous administration of sulprostone. However, we found 4 cases of cardiac arrest and one of pulmonary edema associated with sulprostone administration.6 All of them could have also suffered from a TTC, because there were no detailed data concerning cardiac function in these reports. In our report, two other trigger factors also could have promoted the TTC: the cesarean delivery itself or the oxytocin infusion, which induced a junctional tachycardia with myocardial ischemia. However, the delay between the stressful trigger and the first symptom is usually less than 2h in the published cases of TTC after cesarean delivery.1 Moreover, our patient became transiently asymptomatic when the junctional tachycardia ended. These factors argue in favor of a probable relationship between sulprostone and the TTC.

The lesson gleaned from the described cases is worthwhile: cardiac symptoms, LV systolic dysfunction, or a slight troponin increase after sulprostone administration should lead to a suspicion of TTC. Moreover during cesarean delivery, the differential diagnosis could be an acute coronary syndrome caused by spontaneous coronary artery dissection. These two diseases can be distinguished by TTE and coronary angiography. Clinicians should be aware of this potential adverse effect when monitoring patients receiving sulprostone.

.

Corresponding author: pycourand@hotmail.com