In a recent Position Paper of the European Society of Cardiology,1 the following criteria for diagnosis of myocardial infarction with nonobstructive coronary arteries (MINOCA) were proposed: a) acute myocardial infarction according to the criteria defined by the III universal definition; b) absence of ≥ 50% stenosis on angiography; c) exclusion of other clinically overt specific etiologies. Anxiety and mood disorders seem to be more common in women than in men, and there is emerging evidence linking anxiety to coronary artery disease (CAD) development, particularly among women.2 A previous study demonstrated sex differences in the prevalence of psychiatric disorders in patients with unstable angina.3 Little is known about sex differences in the prevalence of psychiatric symptoms in patients with MINOCA. The aim of this study was to examine the relationship between sex and psychiatric symptoms in patients with MINOCA.

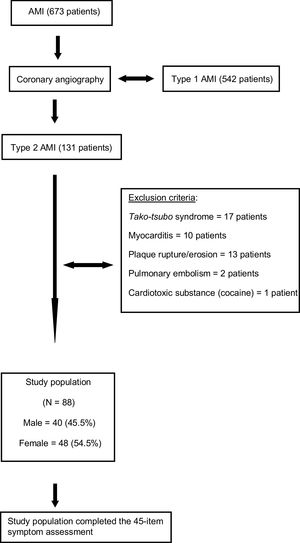

We prospectively evaluated 131 patients with a final etiologic diagnosis of MINOCA who underwent coronary angiography at the Cardiology Department of a University Hospital from October 1, 2011 to December 31, 2017. Nonobstructive CAD was defined as the presence of coronary stenosis > 0% but < 50% of lumen diameter in at least 1 major epicardial coronary artery.1 We excluded 17 patients with a diagnosis of tako-tsubo syndrome confirmed by echocardiography or cardiac magnetic resonance, 10 patients with a suspected diagnosis of myocarditis confirmed by cardiac magnetic resonance, 13 patients without obstructive CAD but with evidence of coronary thrombosis on an unstable plaque confirmed by intravascular ultrasound, 2 patients with coronary embolism, and 1 patient who underwent cardiotoxic substance administration (cocaine). Hence, 88 patients were included in the study (Figure 1). The study was approved by the local ethics committee and all patients gave written informed consent before angiography.

Once their clinical condition had stabilized, all patients completed the 45-item Symptom Assessment (SA-45).4 The SA-45 assesses 9 psychopathological domains: hostility, somatization, depression, anxiety, interpersonal sensitivity, obsession-compulsion, phobic anxiety, paranoid ideation, and psychoticism. Each domain contains 5 items that are scored on a 5-point scale of distress (0, none; 1, a little; 2, moderate; 3, quite a bit; and 4, extreme); the total score reflects the severity of the corresponding psychiatric domain4 (Table 1). In addition, we collected the following variables for the study: age, sex, body mass index, cardiovascular risk factors, left ventricular ejection fraction, psychiatric history in first-degree family members, education level, marital status, and treatment at discharge. The relationship between sex and psychiatric symptoms was analyzed by means of logistic regression. The SPSS v20 was used for all calculations.

SA-45 Questionnaire Results of the Study Population and Baseline Characteristics Between Male and Female Patients With MINOCA

| SA-45 Questionnaire results in 88 consecutive patients with MINOCA | |

|---|---|

| Anxiety | 7.9±3.8 |

| Depression | 5.6±4.4 |

| Interpersonal sensitivity | 5.2±3.8 |

| Hostility | 3.9±3.8 |

| Obsessive-Compulsive | 6.1±3.9 |

| Psychoticism | 2.8±2.7 |

| Paranoid ideation | 8±4.3 |

| Somatization | 4.4±3.3 |

| Phobic anxiety | 3.5±3.5 |

| Baseline characteristics of 88 consecutive patients with MINOCA: comparison between male and female patients | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Men (n=40) | Women (n=48) | P |

| Age, y | 53. 8±8.5 | 52.9±8.4 | .6 |

| Body max index, kg/m2 | 27.8±3.3 | 27.6±3.7 | .8 |

| Hypertension | 22 (55) | 27 (56.2) | .9 |

| Smoker | 20 (50) | 23 (47.9) | .8 |

| Dyslipidemia | 26 (65) | 25 (52.1) | .22 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 12 (30) | 14 (29.2) | .93 |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction, % | 55.8±9.4 | 58.1±9.5 | .25 |

| Higher education | 9 (22.5) | 12 (25) | .8 |

| Previous psychiatric disease | 3 (7.5) | 5 (10.4) | .7 |

| Civil status, married | 26 (65) | 36 (75) | .4 |

| Time to perform the CC, h | 30.3±11.4 | 32.7±11.1 | .31 |

| SA-45 Questionnaire | |||

| Depression | 5.2±3.9 | 5.9±4.8 | .5 |

| Anxiety | 6.8±3.4 | 8.8±3.9 | .15 |

| Interpersonal sensitivity | 5.3±3.3 | 5.2±4.2 | .9 |

| Hostility | 3.5±3.4 | 4.3±4 | .3 |

| Obsessive-compulsive | 6.4±3.4 | 5.8±4.3 | .5 |

| Psychoticism | 2.6±2.3 | 3±3 | .6 |

| Paranoid ideation | 7.7±3.5 | 8.2±4.9 | .6 |

| Somatization | 3.4±2.9 | 5.2±3.4 | .009 |

| Phobic anxiety | 2.4±3.5 | 4.5±3.3 | .004 |

| In-hospital medication | |||

| Antiplatelets | 38 (95) | 48 (100) | .11 |

| Statins | 40 (100) | 48 (100) | * |

| Beta blockers | 17 (42.5) | 20 (41.7) | .9 |

| Calcium channel antagonists | 5 (12.5) | 9 (18.8) | .6 |

| ACEI/angiotensin II antagonist | 11 (27.5) | 21 (43.8) | .13 |

| LMWH | 40 (100) | 48 (100) | * |

| Vasodilators | 36 (90) | 45 (93.8) | .51 |

| Treatment at discharge | |||

| Aspirin | 31 (77.5) | 45 (93.8) | .03 |

| Beta-blockers | 17 (42.5) | 20 (41.7) | .9 |

| Calcium channel antagonists | 5 (12.5) | 9 (18.8) | .6 |

| ACEI/angiotensin II antagonist | 11 (27.5) | 21 (43.8) | .13 |

| Statins | 18 (45) | 30 (62.5) | .22 |

ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; CC, cardiac catheterization; LMWH, low molecular weight heparin; SA-45, Symptom Assessment-45.

Data are presented as No. (%) or mean±standard deviation.

The mean patient age was 53 years, and 45.5% were men. There were no significant differences in cardiovascular risk factors, previous psychiatric history in first-degree family members, education level, or marital status between men and women. Analysis of the psychiatric symptoms showed that women had higher scores than men in somatization and phobic anxiety (Table 1). After adjustment by baseline characteristics, a multivariable logistic regression model showed that the sex difference was statistically significant with a female-male odds ratio for phobic anxiety of 1.2 (95%CI, 1.04-1.40; P=.01).

The main and original finding in our study assessing sex differences in psychiatric symptoms among MINOCA patients was that female patients had higher phobic anxiety than male patients. Anxiety disorders are the most prevalent mental disorders and are associated with immense health care costs and a high disease burden. According to large population-based surveys, up to 33.7% of the population is affected by an anxiety disorder during their lifetime.2 Phobic anxiety, characterized by an unreasonable fear when exposed to specific situations such as enclosed spaces, heights, or crowds, is the predominant complaint in approximately half of these individuals.2

In our study, female MINOCA patients showed significantly higher scores for phobic anxiety than male MINOCA patients. A similar sex distribution was seen in a prior study, in relation to elevated phobic anxiety and female CAD patients.5 Watkins et al.5 reported that phobic anxiety levels were high in women with CAD and may be a risk factor for cardiac-related mortality in women diagnosed with CAD. In that prospective cohort study, 947 CAD patients were included, and participants completed the phobic anxiety subscale of the Middlesex Hospital Questionnaire. CAD was defined as ≥ 75% occlusion of 1 coronary artery. Female CAD patients reported significantly elevated phobic anxiety levels compared with male patients (P < .001). In women, phobic anxiety was associated with a 1.6-fold increased risk of cardiac mortality and a 2.0-fold increased risk of sudden cardiac death but was not associated with increased mortality risk in men. As in our study, Watkins et al.5 found an association between sex and phobic anxiety in patients with CAD. Their population was comparable to ours except that the patients at the time of enrollment had unstable or stable angina and the presence of ≥ 75% stenosis on angiography. In our study, we enrolled only MINOCA patients. Our study has some limitations. First, this is a single-center study. Second, there was no control group. Third, the study population was not large.

Phobic anxiety should be tested in female MINOCA patients, as they reveal novel targets for the development of novel pharmacotherapies that could be specifically tailored to the physiology of women.6

We would like to thank to Dr Aram Morera-Mesa (freelance translator) for his assistance in the translation of this article.