Primary cardiac tumors are rare, with their incidence in early series ranging from 0.001% to 0.3%.1 Sarcomas, especially those originating in the pericardium, are exceedingly rare. In this article, we report a case of primary pericardial synovial sarcoma and review the literature on this tumor with a view to improving knowledge of this entity and its management.

A 58-year-old man was admitted with pericardial chest pain. He had HLA (human leukocyte) B27-positive sacroiliitis, but undertook exercise training. He had no other diseases of note or substance abuse, and there was no known family history of cancer.

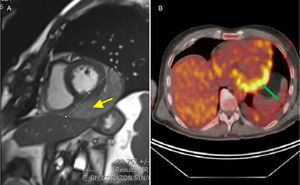

Transthoracic echocardiography, multidetector computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and 18-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) (Figure) demonstrated a 93 x 55mm mass lying over the lateral wall of the left ventricle, without extracardiac spread. It was a friable tumor with necrotic tissue, tightly attached to the heart, and therefore complete resection was impossible. Pericardial synovial sarcoma was diagnosed by histological analysis. After a multidisciplinary approach, the patient was referred for adjuvant chemotherapy and radiotherapy, with good initial response. However, 7 months later, a new MRI scan showed local recurrence of the tumor. Chemotherapy and new surgical resection was performed. However, at the present time, another recurrence has been diagnosed.

Multimodality imaging. A: MRI. Gradient-echo MRI sequence showed a well-delimited mass (arrow) located into the posterior-lateral pericardium. B: FDG-PET. Transverse plane image is shown. Enhanced uptake can be seen in the pericardial mass. FDG-PET, 18-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

Synovial sarcomas are malignant soft tissue tumors with an aggressive growth pattern. Although they arise predominantly in the extremities, they have been reported to occur in almost any organ. They are classified into 4 subtypes depending on the proportion of epithelial and spindle cells: biphasic, monophasic spindle, monophasic epithelial, and undifferentiated. Our patient had a monophasic variant with predominant spindle cells. Immunohistochemical markers, including vimentin, epithelial membrane antigen, and cytokeratin, help to exclude other possible soft tissue tumors.2 A definitive diagnosis can be made based on the presence of a chromosomal translocation, which is present in more than 90% of cases and has not been found to be associated with other sarcomas. This translocation involves the SSX1 or SSX2 gene on the X chromosome and the SYT gene on chromosome 18, forming a fusion gene, SYT-SSX, with the subsequent production of fusion proteins.3,4

The diagnosis is established by multimodality imaging techniques and cytological examination of the tissue. Computed tomography, MRI, and FDG-PET help to determine the location of the tumor and to assess invasion of adjacent organs.5 They are also essential for surgical planning and in post-treatment monitoring.

Management is challenging and requires a multimodal approach. Surgery is the cornerstone of treatment and can lead to curative therapy. However, most often tumors are adherent to adjacent vital organs and are nonresectable. Therefore, external beam radiation therapy and chemotherapy may help to reduce recurrence rates. Doxorubicin and ifosfamide represent the most effective chemotherapeutic agents and may achieve a higher response rate.6 The most common cause of death is local recurrence, even after complete macroscopic resection. As in the case reported here, few patients are recurrence-free at 12 months and therefore most patients require repeat treatments.

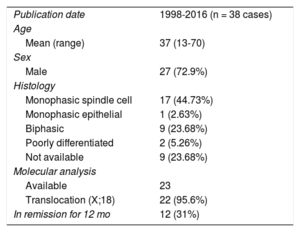

To the authors’ knowledge, few cases of pericardial synovial sarcomas have been reported in the English-language literature. A PubMed search of the term “pericardial synovial sarcoma” yielded only 54 hits in August, 2016. Checking these articles, as well as the articles cited within them, we found only 38 cases of synovial sarcoma originating in the pericardium (Table). We reviewed them for the epidemiology, clinical picture, therapeutic conduct, and prognosis of this neoplasm. There was male predominance, and a higher incidence in the fourth decade of life. Most of the sarcomas were monophasic (spindle cell) type and had a cytogenetic translocation. As is our case, the immunohistochemistry was predominately positive for vimentin, epithelial membrane antigen, and cytokeratin. All of them were treated with surgical excision when possible, with neoadjuvant treatment (chemotherapy and radiation) to reduce local recurrence rates, similar to the management in the case reported here. Complete or near total excision of the tumor was performed in a minority of the reported cases, so most patients had local recurrence or short survival times.

Pericardial Synovial Sarcomas Reported

| Publication date | 1998-2016 (n = 38 cases) |

| Age | |

| Mean (range) | 37 (13-70) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 27 (72.9%) |

| Histology | |

| Monophasic spindle cell | 17 (44.73%) |

| Monophasic epithelial | 1 (2.63%) |

| Biphasic | 9 (23.68%) |

| Poorly differentiated | 2 (5.26%) |

| Not available | 9 (23.68%) |

| Molecular analysis | |

| Available | 23 |

| Translocation (X;18) | 22 (95.6%) |

| In remission for 12 mo | 12 (31%) |

In conclusion, this report describes a case of synovial sarcoma of pericardial origin and an updated review of the literature. This sarcoma has poor prognosis, and a systematic approach to diagnosis and multidisciplinary management are crucial. The histological characteristics of the tumor, the clinical course of the patient, and treatment response should be carefully analyzed in order to establish the optimal therapeutic strategies for treating such extremely rare conditions in the future.

.