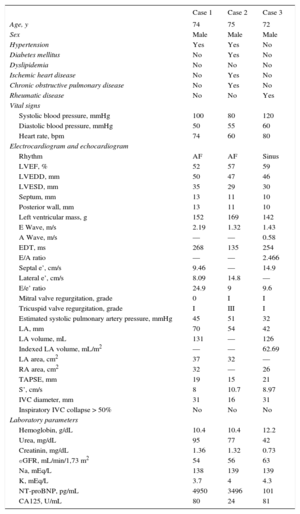

Constrictive pericarditis (CP) usually manifests as systemic congestion and is associated with high morbidity and mortality unless specific maintenance treatment is administered.1,2 Continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis (CAPD) has emerged as a safe and effective alternative treatment in advanced heart failure (HF).3–5 Here, we describe the outcome in 3 patients with CP included in a CAPD program that changes the dialysis solution (1.36%-2.27% glucose) 2 to 4 times a day. The baseline characteristics of the patients are shown in Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics

| Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 74 | 75 | 72 |

| Sex | Male | Male | Male |

| Hypertension | Yes | Yes | No |

| Diabetes mellitus | No | Yes | No |

| Dyslipidemia | No | No | No |

| Ischemic heart disease | No | Yes | No |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | No | Yes | No |

| Rheumatic disease | No | No | Yes |

| Vital signs | |||

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 100 | 80 | 120 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg | 50 | 55 | 60 |

| Heart rate, bpm | 74 | 60 | 80 |

| Electrocardiogram and echocardiogram | |||

| Rhythm | AF | AF | Sinus |

| LVEF, % | 52 | 57 | 59 |

| LVEDD, mm | 50 | 47 | 46 |

| LVESD, mm | 35 | 29 | 30 |

| Septum, mm | 13 | 11 | 10 |

| Posterior wall, mm | 13 | 11 | 10 |

| Left ventricular mass, g | 152 | 169 | 142 |

| E Wave, m/s | 2.19 | 1.32 | 1.43 |

| A Wave, m/s | — | — | 0.58 |

| EDT, ms | 268 | 135 | 254 |

| E/A ratio | — | — | 2.466 |

| Septal e’, cm/s | 9.46 | — | 14.9 |

| Lateral e’, cm/s | 8.09 | 14.8 | — |

| E/e’ ratio | 24.9 | 9 | 9.6 |

| Mitral valve regurgitation, grade | 0 | I | I |

| Tricuspid valve regurgitation, grade | I | III | I |

| Estimated systolic pulmonary artery pressure, mmHg | 45 | 51 | 32 |

| LA, mm | 70 | 54 | 42 |

| LA volume, mL | 131 | — | 126 |

| Indexed LA volume, mL/m2 | — | — | 62.69 |

| LA area, cm2 | 37 | 32 | — |

| RA area, cm2 | 32 | — | 26 |

| TAPSE, mm | 19 | 15 | 21 |

| S’, cm/s | 8 | 10.7 | 8.97 |

| IVC diameter, mm | 31 | 16 | 31 |

| Inspiratory IVC collapse > 50% | No | No | No |

| Laboratory parameters | |||

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 10.4 | 10.4 | 12.2 |

| Urea, mg/dL | 95 | 77 | 42 |

| Creatinin, mg/dL | 1.36 | 1.32 | 0.73 |

| eGFR, mL/min/1,73 m2 | 54 | 56 | 63 |

| Na, mEq/L | 138 | 139 | 139 |

| K, mEq/L | 3.7 | 4 | 4.3 |

| NT-proBNP, pg/mL | 4950 | 3496 | 101 |

| CA125, U/mL | 80 | 24 | 81 |

AF, atrial fibrillation; CA125, carbohydrate antigen 125; EDT, e-wave deceleration time; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; IVC, inferior vena cava; LA, left atrium; LVEDD, left ventricle end-diastolic diameter; LVESD, left ventricle end-systolic diameter; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic protein; RA, right atrium; TAPSE, tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion.

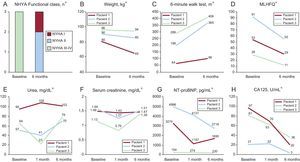

The first patient was a 74-year-old man with a mechanical mitral valve prosthesis and chronic kidney disease. CP was confirmed with imaging techniques (Figure 1 of the supplementary material). After failed pericardiectomy, he progressed to a state of refractory congestive HF and was therefore included in the CAPD program. At 1 and 6 months from the start of treatment, clinical and biochemical parameters improved, with no deterioration in baseline kidney function (Figure). The patient has experienced no decompensation episodes after 16 months of CAPD. Complications included infection of the catheter opening, which was treated in the outpatient setting, and peritonitis, which required hospital admission and temporary catheter withdrawal.

Laboratory parameters, functional capacity, and quality of life after the start of CAPD over time. CA125, cancer antigen 125; CAPD, continuous outpatient peritoneal dialysis; MLHFQ, Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide; NYHA, New York Heart Association functional class. *P<.05 for all comparisons.

The second patient was a 75-year-old man with chronic kidney disease and chronic ischemic heart disease, who had undergone cardiac surgery for perforation and cardiac tamponade after ablation of ventricular tachycardia. A few weeks after surgery, he was admitted for acute HF with clear signs of systemic congestion. Echocardiography and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging revealed early-stage CP (Figure 2 of the supplementary material). The patient responded slowly but satisfactorily to intensive diuretic therapy but experienced an early clinical relapse after hospital discharge. Pericardiectomy was ruled out and he was included in the CAPD program. As for the previous patient, this patient showed clear improvement in the first few weeks, and a noteworthy improvement in laboratory parameters, quality of life, and functional status at 6 months (Figure). At 36 months after starting CAPD, the patient had not been hospitalized although he had experienced 2 episodes of peritonitis treated in the outpatient setting.

The third patient was a 72-year-old man who was admitted for anasarca. He had a history of rheumatoid arthritis and sleep apnea hypopnea syndrome. Diagnosis of CP was confirmed during his hospital stay (Figure 3 of the supplementary material). After discharge, he experienced early clinical relapse despite intensive diuretic therapy. Surgery was ruled out and he was included in the CAPD program. During follow-up, an improvement in functional class, quality of life, and congestion-related biochemical parameters was observed in the first 6 months (Figure). At 12 months, he remained in New York Heart Association functional class I. During this time, there were no readmissions and no CAPD-related complications.

This is the first series to show that CAPD could be a therapeutic alternative in patients with CP. Observational studies suggest that CAPD is effective in patients with HF, refractory congestion, and a certain degree of concurrent kidney dysfunction.3–5 These studies have shown a marked decrease in fluid overload and improved functional capacity, quality of life, and prognosis, with an acceptable safety profile and additional cost.3–5 In addition, this technique has a series of noteworthy additional theoretical and logistic advantages. First, the technique is relatively simple and is used in the outpatient setting. Second, it maintains residual kidney function. Third, it provides a slow and continuous ultrafiltration, which is associated with hemodynamic stability.3–5

The present case series shows that implementation of CAPD in patients with HF is feasible. This technique is associated with a substantial decrease in parameters related to the severity of fluid overload (weight and plasma concentrations of cancer antigen 125 and natriuretic peptides) and with improved functional capacity and quality of life.

In view of these preliminary findings, CAPD could be considered as an alternative to pericardiectomy for patients with advanced CP and high surgical risk or as a bridge to surgery after postsurgical relapse. In our series, 2 of the patients had a history of prior cardiac surgery (1 had undergone failed pericardiectomy).

These results should be confirmed with larger series of patients and in a more controlled setting. As in the case of CP, it is particularly important to identify clinical characteristics that may identify patients who a priori most stand to benefit from this technique of ultrafiltration.

FUNDINGThe present study was partly funded with a grant from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III and FEDER, Red de Investigación Cardiovascular, Program 7 (RD12/0042/0010) and PIE15/00013.