To the Editor,

Superior vena cava (SVC) syndrome arises when there is decreased or obstructed blood flow through the SVC.

Depending on the severity of the symptoms and the etiology, the treatment indicated can be surgery, at times with a venous-venous shunt. Baloon angioplasty and stenting have also been developed as an alternative to conventional surgery.

From January 1993 through December 2011, 5 patients presented in our hospital with this syndrome and all were treated percutaneously without any complications: 1 with balloon angioplasty,1 1 with a conventional stent, and 3 with polytetrafluoroethylene-coated stents. Table summarizes the main characteristics of patients and the treatment given.

Baseline Clinical Characteristics and Angiographic Parameters for the Patients

| Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 | Patient 4 | Patient 5 | |

| Sex | Male | Male | Male | Male | Female |

| Age | 12 | 47 | 68 | 74 | 10 |

| Clinical symptoms | Jugular distension and severe superficial thoracic circulation | AVB; Edema of the neck and collateral venous circulation | AVB; facial congestion and collateral venous circulation | Brugada; impossible to place new electrode | Edema of the neck and collateral venous circulation |

| Obstruction | Subtotal | Long total (3 cm) | Short total (2 cm) | Subtotal | Subtotal |

| SVC/RA gradient | 17 | 7 | 11 | 3 | 7 |

| Etiology | APPVD | APPVD; PM electrode | PM electrode | ICD electrode | APPVD |

| Time from intervention until percutaneous treatment | 6 months | 6 years since surgery and 4 months since PM | 9 years 1 month | 6 years 10 months | 8 years |

| Type of surgery/PM | Opening of atrial septum and tunneling with patch | Widening of SVC with patch and drainage of anomolous veins via an AS; PM DDD | PM DDD | ICD | Widening of SVC with patch and opening atrial septum and tunneling with patch |

| Balloon | Match® 7×40 | Balt® 20×50 | BiB® 18×50/9×40 | Maxi LD 14 × 30 | Optapro 12×30 |

| Stenting | No | Covered Stent Numed 8Z 45 mm | Covered Stent Numed 8Z 35 mm | Covered Stent Numed 8Z 45 mm | Palmaz XD 29 |

| Post-dilatation balloon | Monofoil 15×40 | Mullins 18×30 | No | Mullins 16×30 y 18×30 | No |

APPVD, abnormal partial pulmonary vein drainage; AS, atrial shunting; AVB, atrioventricular block; ICD, implantable cardioverter/defibrillator; PM, pacemaker; RA, right atrium; SVC, superior vena cava.

With regard to the technique used, in cases with anterograde flow, approach was via the jugular vein with 5 or 6 Fr multipurpose catheters (Cordis), through which a straight 260cm straight guidewire of 0.035” diameter (Boston) was introduced. This in turn was snared in the right atrium (RA) by means of a 15-mm Goose Neck® loop (ev3). Venous-venous flow was established with a femoral approach.

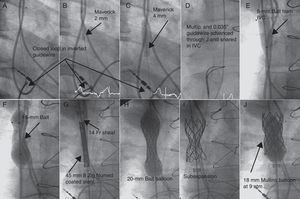

In 2 patients with complete obstruction, we positioned a 15-mm Goose Neck® loop with a femoral approach at the base of the RA and introduced an inverted 0.014” diameter PT Graphix® coronary guidewire (Boston) through a multipurpose catheter. The guidewire was advanced with 2D angiographic guidance parallel to the pacemaker electrode. Once passed the obstruction, we snared the rigid end of the guidewire with the loop and lowered it to the RA (Figure). We then dilated with 2-, 3-, and 4-mm Maverick® coronary balloons (Boston) (Fig. B and C) before advancing the multipurpose catheter through the tunnel created and replaced the coronary guidewire with a 0.035” guidewire that was extracted via the femoral vein to establish the jugulofemoral bypass (Fig. D).

Figure. Angiographic images of the procedure to remove the obtstruction of the superior vena cava. IVC, inferior vena cava.

In the case of simple angioplasty, we used Balt™ 7- and 15-mm balloons, introduced via the femoral artery. For stenting procedures, a femoral approach was also used. In all cases, predilatation was performed with 8- and 15-mm balloons (Fig. E and F) to introduce the 9 and 14 Fr Mullins sheaf (Cook) until reaching the SVC (Fig. G). Three 45-mm polytetrafluoroethylene coated stents and 8 Zig® (Numed) and 1 Palmaz® XD 29 (Cordis) stents were used. These were mounted in their own balloons with the balloon/SVC ratio =1 (Fig. H, Table). In 2 cases, the underexpanded stent was redilated at high pressure (9 atm) with the Mullins balloon (Fig. I and J).

In all cases, the obstruction was completely removed and all patients were discharged from hospital after 24h with antiplatelet treatment for patients 1, 2, 4, and 5, and anticoagulant therapy for patient 3.

All patients have remained asymptomatic since the procedure, with a mean follow-up of 46.6 months (range, 9-120 months). After 1 year, the patency of the coated stent was confirmed by magnetic resonance imaging in patient 1 and chest computed tomography in patients 2 and 3. The pacemakers implanted in patients 2 and 3 were checked in the arrhythmia unit, and they were found to be working properly.

There is limited existing experience in the treatment of SVC obstruction, with an initially positive hemodynamic outcome in all patients treated by stenting and 78% of those treated by balloon angioplasty, without any long-term differences in outcome between the 2 percutaneous options.2

In patients who are also bearers of a cardiac pacing electrode, 3 strategies have been considered: simple balloon angioplasty, with the risk of restenosis due to recoil; initial withdrawal of the lead followed by removal of the obstruction by implantation of a coated or conventional stent; or placement of a new pacemaker.3, 4 This last option reduces the risk of restenosis and electrode damage, but it requires a new pacemaker to be placed.

One final measure consists of implanting a stent without removing the lead, which remains trapped between the venous wall and the stent.5 With this strategy though, there is a risk of immediate pacemaker dysfunction due to the metallic scaffold, although there is now some experience on this point that shows normal function of pacemakers immediately after the procedure. However, the long-term effects arising because the electrode comes into repeated contact with the end of the stent are unknown. Cardiac motion itself could generate a point of fatigue because the lead is fixed by the stent.6 It is also difficult to remove in the event of infection or thrombosis. This last approach could be of interest in patients in whom it is impossible or very difficult to remove the lead and/or in very elderly patients or those with a short life expectancy.

Our group proposes the use of coated stents in order to avoid possible acute and chronic deterioration of the electrode, given that the coating itself could help cushion the compression of the lead until neoendothelization has occurred.

.

Corresponding author: koldobika.garciasanroman@osakidetza.net