A 58-year-old man, who had quit smoking 16 years previously and had no other modifiable cardiovascular risk factors, presented with a several-month history of episodes of anginal chest pain triggered by emotional stress. The physical examination was unremarkable.

Electrocardiography revealed a sinus rhythm of 75 bpm, with normal atrioventricular conduction, incomplete right bundle branch block, and no signs of ischemia or necrosis.

Echocardiography showed normal-sized chambers, with good biventricular contractility and dilatation of the tubular portion of the ascending aorta (44 mm), with mild aortic regurgitation of the tricuspid valve but no other noteworthy abnormalities.

A clinical diagnosis of stable angina was made and conventional stress testing was performed, which was positive due to the presence of pain at a submaximal heart rate, without associated repolarization abnormalities.

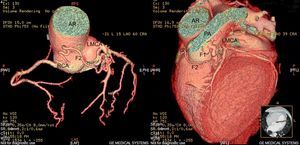

In view of these findings, we considered the probability of the presence of major coronary lesions to be low. Accordingly, we ordered a multidetector computed tomography (CT) scan, which showed no coronary lesions but revealed the presence of an irregular fistula that, from its origin in the right Valsalva sinus, cranial to the ostium of the right coronary artery, passed in front of the trunk of the main pulmonary artery before terminating in the left main coronary artery; at this site, another possible fistulous tract was observed that passed cranially and anteriorly to the pulmonary artery. However, visualization of this fistula was disrupted at this point by defects in image processing (Fig. 1).

Computed tomography angiography. A coronary artery fistula was seen between the Valsalva sinus of the right coronary artery and the left main coronary artery. Notice a first fistulous tract running anterior to the pulmonary artery and a second fistulous tract near to its termination, which seems incomplete. AR, aortic root; F1, first fistulous tract; F2, second fistulous tract; LMCA, left main coronary artery; PA, pulmonary artery; RCA, right coronary artery.

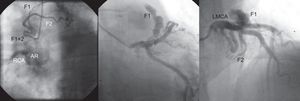

The above findings were confirmed by coronary angiography (Fig. 2), but an additional fistulous tract was identified that shared an origin and termination with the fistula detected by CT. Dilatation of the ascending aorta was also seen, without visualization of stenosis of the coronary arteries.

Coronary angiography. The aortic root and a fistula originating in the right Valsalva sinus, independent of the orifice of the right coronary artery, which immediately bifurcates into 2 fistulous tracts (F1 and F2) that reconnect before terminating in the left main coronary artery. AR, aortic root; F1, first fistulous tract; F2, second fistulous tract; LMCA, left main coronary artery; RCA: right coronary artery.

Because the symptoms were mild, and their relationship with the fistula was unclear, we opted for medical treatment and, taking into account the aneurysm of the ascending aorta, also prescribed beta-blockers. Moreover, the risk of coronary artery fistula rupture has rarely been described, and there is no evidence that would have justified a more invasive approach. The patient showed marked clinical improvement and only experienced sporadic anginal episodes that were exclusively associated with sexual intercourse. These episodes were resolved by prescription of oral nitrates.

Congenital coronary fistulas are rare and generally isolated.1 These anomalies are described as a connection between one or various coronary arteries and a cardiac chamber or large vessel.2,3 However, we found no cases in the literature describing a fistulous tract that connected a coronary artery with the aorta. The mechanism by which coronary fistulas usually cause angina is ischemia due to “coronary steal”,4,5 which does not explain the symptoms in our patient, given that it would involve an excessive flow from the aorta to the left coronary artery. A likely cause of the ischemia was endothelial dysfunction secondary to excessive flow or thrombosis of the angulated and tortuous fistulous tracts. This shape favors blood stasis, which is a documented cause of infarction1 in conventional coronary artery fistulas, although our patient had angina, not infarction. It is also important to stress the accuracy of multidetector CT in precisely defining the abnormal origin and path of the anomalous coronary arteries and their relationship with other structures,6 because it is sometimes difficult to visualize the course of the coronary arteries though conventional coronary angiography. CT can be considered the diagnostic method of choice in cases of clinical angina that are not explained by coronary artery lesions and which could be secondary to congenital abnormalities of the coronary artery. Nevertheless, we consider the use of coronary angiography to be appropriate because, in addition to confirming the diagnosis of a fistula, this technique provides complementary information about its connections, the bidirectional nature of the flow, and the coexistence of other tracts that escape the spatial resolution of CT, either due to their reduced diameter or to their omission from the sample volume imaged.

The use of image-based ischemia detection, whose usefulness would probably have been enhanced by the administration of vasodilator stress agents, could also have provided useful information on the presence of ischemia and its location and severity.