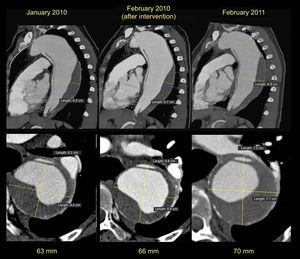

We report the case of a 55-year-old woman with no remarkable history who had a type B aortic dissection in August 2008. Computed tomography showed a large dissection opening after the exit of the left subclavian artery and extending to the iliac bifurcation. The descending thoracic aorta was dilated (60mm) with partial thrombosis of the false lumen. The aortic valve was trileaflet and showed normal function, and the ascending aorta was of normal size. In the absence of acute complications, treatment with beta-blockers was chosen and endovascular treatment was deferred. Since the aortic arch had an acute angle, and the distance between the subclavian artery and the left carotid was short, there was insufficient neck for proximal stent implantation, and consequently a 2- pronged intervention was indicated: an aortobicarotid bypass followed by endovascular treatment. In February 2010, we proceeded with the aortobicarotid bypass, which was complicated by retrograde dissection of the ascending aorta from the clamp point and so the middle and distal ascending aorta were replaced with a Hemashield 28 vascular prosthesis. Follow-up showed progressive dilation of the descending thoracic aorta (Figure 1), despite which the patient refused all intervention.

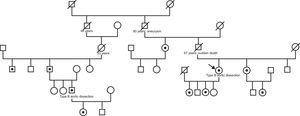

In August 2011, the patient reported that the 38-year-old son of a second cousin had experienced a type B aortic dissection. This relative, who had no previous history, had been admitted to another hospital for aortic dissection originating after the exit of the left subclavian artery and progressing to the iliac bifurcation. At the time of the dissection, there was a slight dilation of the descending thoracic aorta (39mm), with a trileaflet and normally functioning aortic valve and without dilatation of the remaining aortic segments. The diagnostic approach then shifted to familial aortic disease; a thorough physical examination of both patients was performed, which showed no signs of Marfan or Loeys-Dietz syndrome, and a genetic analysis of the ACTA2 gene (encoding isoform 2 of alpha actin in vascular smooth muscle cells) in the second patient was requested. The analysis showed a novel heterozygous mutation (c.253G>A) resulting in an amino acid change (p.Glu85Lys). The same mutation was also detected in the index case and in the father, paternal uncle and the daughter of the second case, and in the sister, paternal aunt, daughters, and niece of the index case (Figure 2). None of the ACTA2 mutation carriers had iris flocculi or livedo reticularis, characteristics that have previously been described in the context of mutations in this gene.1 Considering the familial aortic disease and aortic fragility observed during surgery, it was decided to avoid endovascular treatment and the patient underwent open surgery to replace the descending thoracic aorta with a tube graft with reimplantation of the visceral vessels.

Although most type B aortic dissections occur in middle-aged patients with hypertension and/or atherosclerosis, a considerable proportion of patients show early presentation with a likely, but not well-understood, genetic basis. In the absence of an identifiable syndrome, up to 21.5% of patients with aortic aneurysms have a family history; genetic mutations are identified in 20%,2 the most common being the mutation in ACTA2 (10-14%).3 This mutation is associated with aortic disease with 48% penetrance and variable expressivity, most often in the form of type A aortic dissections, even with nonsignificantly dilated aortic diameters, and isolated cases of type B4 dissections; it has also been associated with premature coronary artery and cerebrovascular disease.1

Although family screening with imaging of the first-degree relatives of patients with premature aortic disease may be reasonable, indications for genetic analysis are not well established. The clinical practice guidelines of the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology recommend screening for mutations in ACTA2 in cases of familial aggregation of aortic disease5. However, it is important to note that penetrance is low and expressivity variable, which makes it difficult to track asymptomatic carriers of the mutation.

A noteworthy aspect of this case is the importance of the suspected diagnosis of familial aortic disease in young patients with aortic disease, which should make us insist on questioning patients about their family history and rule out syndromic cases. Another important point is that the diagnosis of familial aortic disease makes it reasonable (without the support of clinical trials) to change therapeutic strategies. As in Marfan syndrome and other connective tissue diseases,6 stent implantation may be contraindicated unless used as a bridge to surgery. Finally, it should be borne in mind that familial aortic disease may affect only the descending aorta and there is a risk of dissection even without marked aortic dilation.

The authors thank Mrs. Francesca Huguet, a nurse at the Marfan Unit, for her invaluable collaboration.