Patients with autoimmune disease have worse short-term prognosis after acute coronary syndrome (ACS).1–3 Studies are needed in Spain to analyze the possible reasons for this and to determine long-term prognosis after discharge from hospital.

This was a retrospective observational study of patients admitted to a tertiary hospital for ACS between January 2011 and February 2016. The study was conducted according to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the ethics committee of the hospital.

The primary objective was to determine the prognostic influence of autoimmune disease on all-cause death, type 3 to 5 major bleeding according to the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium classification,4 and a composite endpoint of nonfatal acute myocardial infarction and stroke. The primary objective was assessed in patients who were alive after at least 1 year of follow-up (n = 1742). Events were recorded by telephone contact or extracted from medical records. The secondary objective was to determine the characteristics, presentation, and treatment of ACS in patients with and without autoimmune disease. For this objective, the overall population was analyzed (n = 2236).

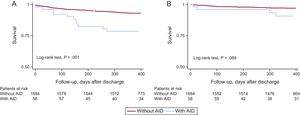

The effect of autoimmune disease was calculated by Cox regression with adjustment for age, diabetes mellitus, atrial fibrillation, peripheral vascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, neoplasms, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, Killip score ≥ 2 on admission, heart rate, systolic blood pressure, hemoglobin, troponin T, glomerular filtration rate, left main coronary artery disease and/or 3-vessel coronary artery disease, and ventricular function. The cumulative incidence of events was estimated with the Kaplan-Meier method and was compared using the log-rank test.

Among patients with ACS, 74 had autoimmune disease (prevalence of 3.3%). Of these, the most prevalent were rheumatoid arthritis (24 patients), spondyloarthritis (14 patients), and inflammatory bowel disease (10 patients). The median duration of autoimmune disease was 14 years (interquartile range, 4-14 years). Seventy percent of the patients were receiving corticosteroid treatment, 50% disease-modifying therapy/immunosuppressants, 22% anti-inflammatory agents, and 8% biological therapy.

There was a higher prevalence of atrial fibrillation and obstructive pulmonary disease in patients with autoimmune diseases as well as higher systolic blood pressure, heart rate, hemoglobin, and ejection fraction. In both groups, coronary angiography and revascularization (preferentially percutaneous) were performed in a high percentage of patients (84% in both groups; P = .901). Complete revascularization and use of drug-eluting stents were reported in similar percentages of patients (Table). There was a higher proportion of left main coronary artery disease and/or 3-vessel coronary artery disease in patients without autoimmune disease (21% vs 11%, P = .043).

Differences in Baseline Characteristics, Presentation, and Additional Tests According to the Presence of Autoimmune Disease

| Variables | Without AID | With AID | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients, n | 2162 | 74 | |

| Baseline characteristics | |||

| Age, y | 68 ± 13 | 67 ± 13 | .863 |

| Males | 1603 (74) | 51 (69) | .310 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1044 (48) | 29 (39) | .122 |

| Hypertension | 1573 (73) | 52 (70) | .632 |

| Dyslipidemia | 1595 (74) | 55 (74) | .921 |

| Smoking | 1248 (58) | 47(64) | .323 |

| Prior ischemic heart disease | 863 (40) | 30 (41) | .917 |

| Chronic heart failure | 115 (5) | 5 (7) | .590 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 255 (12) | 6 (8) | .331 |

| Peripheral artery disease | 174 (8) | 9 (12) | .205 |

| Atrial fibrillation/flutter | 312 (15) | 19 (26) | .008 |

| Malignancy | 100 (5) | 2 (3) | .435 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 226 (11) | 18 (24) | < .001 |

| Signs and symptoms | |||

| Chest pain | 1819 (85) | 60 (81) | .885 |

| Dyspnea | 118 (6) | 6 (8) | .833 |

| Cardiac arrest | 51 (2) | 2 (3) | .939 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 134.4 ± 28.0 | 127.6 ± 28.1 | .038 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg | 72.6 ± 15.2 | 70.8 ± 15.2 | .309 |

| Heart rate, bpm | 76.6 ± 18.8 | 82 ± 20.1 | .014 |

| Killip score ≥ 2 | 486 (23) | 22 (30) | .152 |

| Laboratory parameters | |||

| Glucose, mg/dL | 162.1 ± 80.2 | 165.7 ± 82.5 | .702 |

| Glomerular filtration rate (MDRD), mL/1.73 m2 | 77.6 ± 27.2 | 71.7 ± 26.1 | .066 |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 13.8 ± 1.9 | 13.1 ± 2.2 | .001 |

| Ultrasensitive troponin T, ng/L | 31 [8-159] | 31 [3-254] | .883 |

| Revascularization strategy | |||

| Coronary angiography | 1886 (89) | 65 (88) | .862* |

| Revascularization | 1556 (84) | 54 (84) | .901 |

| Complete revascularization | 1064 (57) | 35 (55) | .853 |

| Percutaneous intervention | 1469 (78) | 53 (82) | .516 |

| Use of drug-eluting stents | 1145 (61) | 35 (54) | .280 |

| Myocardial revascularization surgery | 80 (4) | 1 (2) | .283 |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction, % | 53.8 ± 12.2 | 50.2 ± 15.6 | .016 |

AID, autoimmune disease; MDRD, Modification of Diet in Renal Disease 4.

Unless otherwise indicated, values are expressed as n (%), mean ± SD, or median [interquartile range].

A numerically higher proportion of patients was treated with clopidogrel as the second antiplatelet agent in patients with autoimmune disease (81% vs 71%, P = .079). No differences were detected in the use of other drugs used for secondary prevention (P > .1 for all comparisons).

After a median follow-up of 397 days (interquartile range, 375-559 days), patients with an autoimmune disease had a higher mortality rate on discharge (25.8% vs 10.9%; log-rank test, P = .001) (Figure A). Of the 15 deaths in patients with autoimmune disease, 11 were of cardiovascular causes (7 sudden deaths and 4 due to acute myocardial infarction). Major bleeding tended to occur more frequently in patients with autoimmune disease (10.3% vs 4.2%; log-rank test, P = .089), and almost 70% were of gastrointestinal origin (Figure B).

Autoimmune disease is an independent risk factor for death after discharge (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 1.95; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.05-3.62; P,=,.035). There was a trend toward a higher risk of major bleeding events (aHR = 2.35; 95% CI, 1.0-6.9; P = .055). The aHR for stroke and repeat infarction was 1.66 (95%CI, 0.77-3.61; P = .200).

Our series provides relevant information on long-term prognosis, with follow-up of more than 1 year, which has not been reported previously.1–3 The majority of deaths in patients with autoimmune disease were of cardiovascular causes, and therefore a certain vulnerability persists after ACS despite similar treatment and clinical presentation. These patients are also vulnerable to bleeding. Recently, it has been shown that a combination of traditional risk factors, atherosclerotic load, and extent of coronary artery disease can identify patients at long-term risk after ACS, but the predictive power is moderate.5 The risk of long-term bleeding risk is, on the other hand, is only weakly predicted.6 In view of our results, autoimmune disease may be considered a comorbidity that can help in general stratification of our patients after ACS.

Given the limited number of patients with autoimmune disease, we pooled them together for analysis, and therefore this population comprised a heterogenous group. Another limitation of the study is that the specific treatment was recorded on admission for ACS but not in the preceding years, which would have better reflected the temporal relationship.