Patients with congenital heart disease may have pulmonary hypertension secondary to increased pulmonary flow, persistent hypoxemia, or elevated left-side filling pressures.1 Persistently elevated pulmonary pressure causes pulmonary vasculature remodeling and pulmonary hypertension refractory to vasodilator therapy. Previous reports have described the anatomic-pathologic changes in pulmonary vasculature and their importance.2,3 Pulmonary hypertension may be a contraindication for heart transplantation. However, it is difficult to determine the pulmonary resistance value that should be used to contraindicate heart transplantation. Recommendations for pediatric patients are based on experience with adults, and the latest guidelines4 establish an upper limit of 6 UW/m2 after the administration of pulmonary vasodilator therapy. Nevertheless, some authors defend the possibility of heart transplantation at higher values.5

From December 2008 to December 2013, we performed 22 heart transplantations in pediatric patients, among them, 5 patients with severe pulmonary hypertension. The characteristics of these patients are described in the Table. All patients underwent catheterization prior to transplantation, except for 1 patient whose pulmonary pressure was estimated by echocardiography. Pulmonary resistances were calculated at baseline and after the administration of pulmonary vasodilator therapy (nitric oxide). Patient 4 was on the transplantation waiting list for 2 years, but had considerable clinical deterioration with the development of severe pulmonary hypertension (Table); hence, a decision was made to implant a left ventricular assist device and administer pulmonary vasodilator therapy. One month later, the catheterization was repeated and pulmonary resistances had dropped to 3.5 UW/m2 and, therefore, the patient was put back on the transplantation waiting list.

Patient Characteristics

| Patient | Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 | Patient 4 | Patient 5 |

| Sex | Female | Male | Male | Male | Male |

| Age, y | 15 | 1.5 | 15 | 5 | 14 |

| Heart disease | Pulmonary atresia | Aortic stenosis | Aortic stenosis | Restrictive cardiomyopathy | Restrictive cardiomyopathy |

| Baseline PAP, mmHg | 122/62/81 | 79/34/54 | 80 | 93/40/63 | 48/32/39 |

| Baseline PVR, UW/m2 | 27.3 | 12.2 | 13.6 | 6.2 | |

| Test PAP, mmHg | 110/53/75 | 46/29/37 | 82/38/57 | 47/30/37 | |

| Test PVR, UW/m2 | 6 | 4 | 6.3 | 5.5 | |

| RV dysfunction | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Posttransplantation support | Vasodilator and inotropic | ECMO | Vasodilator and inotropic | ECMO | Vasodilator and inotropic |

| Time course of PAP | Normal levels within 1 y | Normal levels within 6 mo | Normal levels within 1 y | Normal levels within 6 mo | |

| Patient status | Alive | Death due to HR | Alive | Alive | Alive |

Baseline PAP, baseline pulmonary artery pressure (systolic/diastolic/mean); BH, Berlin-Heart; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; HR, humoral rejection; PVR, pulmonary vascular resistances; RV, right ventricle; test PAP, pulmonary artery pressure after the pulmonary vasodilator test.

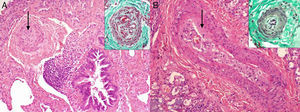

One patient died in the acute phase of the postoperative period due to humoral rejection. All other patients are alive and progressing well. Two patients (40%) required mechanical assistance, 1 due to humoral rejection and the other due to right ventricular dysfunction. All had moderate-to-severe right ventricular dysfunction and required inotropic support and pulmonary vasodilator therapy. In the patients without pulmonary hypertension, right ventricular dysfunction was observed in 9 of 17 (53%; P<.05). Pulmonary vasodilator therapy was maintained at discharge (oral sildenafil), but all patients discontinued the drug during follow-up. Pulmonary biopsies were obtained in 2 patients (Figure) and showed the entire spectrum of vascular lesions characteristic of pulmonary hypertension, with involvement of preacinar and intraacinar arterial vessels, such as plexiform vasculopathy. A venous condition was also observed in the form of hypertrophy. In 1 patient (Figure A), there was a predominance of medial hypertrophy changes in preacinar vessels and plexiform vasculopathy. In the other patient (Figure B), these changes were less serious, but greater intimal thickening was observed, as well as venous involvement with lymph vessel dilation.

A: Hematoxylin-eosin staining which shows a preacinar artery with cellular hypertrophy of the middle layer and large loss in lumen diameter (arrow). The upper box (Masson trichrome stain) shows another preacinar artery with plexiform changes. B: Hematoxylin-eosin staining of a preacinar artery with intimal thickening (arrow). The upper box (Masson trichrome stain) shows an intraacinar arteriole with muscle hypertrophy.

Comparison of these patients with those without pulmonary hypertension showed no statistically significant differences in survival: 80% of patients with pulmonary hypertension survived compared with 88% of patients without hypertension, with a mean follow-up of 27 (10-62) and 29 (7-60) months, respectively (P>.5). We did observe a higher incidence of cellular (80% vs 24%; P=.02) and humoral (80% vs 12%; P<.01) rejection in patients with pulmonary hypertension, probably due to the greater complexity in this subgroup: 80% of patients with pulmonary hypertension compared with 29% in those without pulmonary hypertension underwent more than 1 cardiac surgery prior to transplantation, including placement of a ventricular assist device (P=.04). Only 2 patients, 1 in each group, had developed antihuman leukocyte antibodies (HLA) before transplantation.

In conclusion, it is difficult to establish a value of pulmonary resistance that could be used to contraindicate heart transplantation. Likewise, when referring to pulmonary resistances, the term irreversible should be used with caution because these resistances tend to drop over time and can even become normal. Additionally, the prognostic value of pulmonary biopsy is also unclear. The absence of fibrosis, as in our patients, may be a marker of reversibility. Pulmonary vasodilators and ventricular assistance have been shown to be useful as a bridge to eligibility in both adult and pediatric patients,6 as they allow transplantation in patients initially rejected due to pulmonary hypertension. This strategy may be preferable to cardiopulmonary transplantation.