Stenting of ductus arteriosus in patients with congenital heart disease and duct-dependent pulmonary flow has a long history and validated outcomes.1,2

Our objective was to retrospectively review our experience of this technique. We collected cases of patients born between January 2008 and July 2019, who had been discussed at medical-surgical meetings and referred for ductal stenting based on their underlying heart defect, comorbidities, and ductal anatomy. A total of 32 neonates were included.

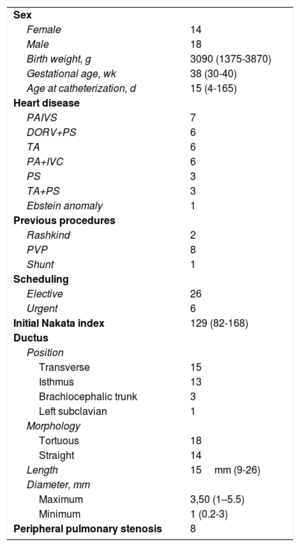

Table 1 shows the patients’ characteristics; the most common defect was pulmonary atresia with intact ventricular septum (PAIVS), with 7 cases.

Patient characteristics

| Sex | |

| Female | 14 |

| Male | 18 |

| Birth weight, g | 3090 (1375-3870) |

| Gestational age, wk | 38 (30-40) |

| Age at catheterization, d | 15 (4-165) |

| Heart disease | |

| PAIVS | 7 |

| DORV+PS | 6 |

| TA | 6 |

| PA+IVC | 6 |

| PS | 3 |

| TA+PS | 3 |

| Ebstein anomaly | 1 |

| Previous procedures | |

| Rashkind | 2 |

| PVP | 8 |

| Shunt | 1 |

| Scheduling | |

| Elective | 26 |

| Urgent | 6 |

| Initial Nakata index | 129 (82-168) |

| Ductus | |

| Position | |

| Transverse | 15 |

| Isthmus | 13 |

| Brachiocephalic trunk | 3 |

| Left subclavian | 1 |

| Morphology | |

| Tortuous | 18 |

| Straight | 14 |

| Length | 15mm (9-26) |

| Diameter, mm | |

| Maximum | 3,50 (1–5.5) |

| Minimum | 1 (0.2-3) |

| Peripheral pulmonary stenosis | 8 |

DORV, double outlet right ventricle; IVC, interventricular communication; PA, pulmonary atresia; PAIVS, pulmonary atresia with intact ventricular septum; PS, pulmonary stenosis; PVP, pulmonary valvuloplasty/valvulotomy; TA, tricuspid atresia; TF, tetralogy of Fallot.

Values are expressed as absolute number of cases or median (range).

We provided prostaglandin E1 at the dose required to achieve preprocedure saturations of 70% to 75%. For patients with possibly transient (days to at least a week) duct dependence (such as PAIVS, pulmonary stenosis following valvuloplasty, or Ebstein anomaly), we waited 2 to 3 weeks before performing the procedure; in all other cases, it was performed within the first 7 to 10 days.

The location and characteristics of the ductus (eg, tortuosity or peripheral pulmonary stenosis) are prognostic factors for procedural success and duration,3 allowing a distinction to be made between complex and relatively noncomplex (normally-positioned and straight) cases.

It is not uncommon to find peripheral pulmonary stenosis (25%) due to the presence of ductal tissue in the branches, which in severe cases requires the placement of longer stents to fully cover the ductus and also treat the peripheral stenosis.4

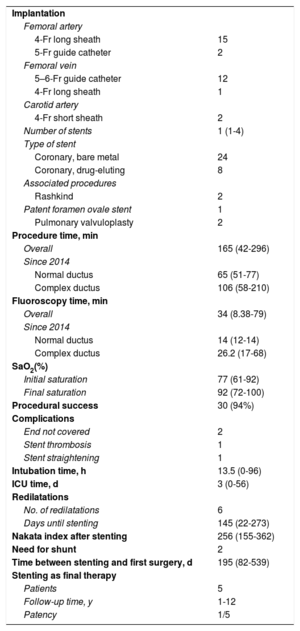

Table 2 provides information on the procedure and follow-up. The procedure was always carried out under general anesthetic. In normally-positioned ductus, access was usually via the femoral artery using a 4-Fr long sheath for implantation. In other locations, access was via the femoral vein with transcardiac passage of a 5–6-Fr guide catheter or a 4-Fr long sheath, plus access via the carotid artery with a 4-Fr short sheath. Fluoroscopy and procedure times decreased with experience, and are currently very short, especially in noncomplex ductus cases; the difference in times between complex and noncomplex cases was not statistically significant, due to the sample size.

Procedure and outcomes

| Implantation | |

| Femoral artery | |

| 4-Fr long sheath | 15 |

| 5-Fr guide catheter | 2 |

| Femoral vein | |

| 5–6-Fr guide catheter | 12 |

| 4-Fr long sheath | 1 |

| Carotid artery | |

| 4-Fr short sheath | 2 |

| Number of stents | 1 (1-4) |

| Type of stent | |

| Coronary, bare metal | 24 |

| Coronary, drug-eluting | 8 |

| Associated procedures | |

| Rashkind | 2 |

| Patent foramen ovale stent | 1 |

| Pulmonary valvuloplasty | 2 |

| Procedure time, min | |

| Overall | 165 (42-296) |

| Since 2014 | |

| Normal ductus | 65 (51-77) |

| Complex ductus | 106 (58-210) |

| Fluoroscopy time, min | |

| Overall | 34 (8.38-79) |

| Since 2014 | |

| Normal ductus | 14 (12-14) |

| Complex ductus | 26.2 (17-68) |

| SaO2(%) | |

| Initial saturation | 77 (61-92) |

| Final saturation | 92 (72-100) |

| Procedural success | 30 (94%) |

| Complications | |

| End not covered | 2 |

| Stent thrombosis | 1 |

| Stent straightening | 1 |

| Intubation time, h | 13.5 (0-96) |

| ICU time, d | 3 (0-56) |

| Redilatations | |

| No. of redilatations | 6 |

| Days until stenting | 145 (22-273) |

| Nakata index after stenting | 256 (155-362) |

| Need for shunt | 2 |

| Time between stenting and first surgery, d | 195 (82-539) |

| Stenting as final therapy | |

| Patients | 5 |

| Follow-up time, y | 1-12 |

| Patency | 1/5 |

ICU, intensive care unit; SaO2, oxygen saturation.

Values are expressed as absolute number of cases or median (range).

Our patients required a median 13 hours’ intubation and 3 days’ stay in the ICU after the procedure.

The overall success rate was 94% but rose to 100% for cases after 2014. The unsuccessful cases (2/32) corresponded to the initial phase of the series and were due to lack of guidewire stability in complex cases.

The stents used were coronary stents, with a median 1 stent per patient; the last 8 stents implanted were drug-eluting stents to reduce neointimal growth.

Initially, as thromboprophylaxis, we used enoxaparin for 48hours, followed by aspirin. Currently, with drug-eluting stents, we use enoxaparin plus aspirin for 48hours and then switch to aspirin plus clopidogrel.

The mortality rate was 0%. There were no significant vascular complications, and the prevalence of complications in the whole series was 13%, which decreased to 8% in procedures performed after 2014. Complications consisted of the following: need for recatheterization in the days after the procedure due to uncovered ductal ends (1 aortic and 1 pulmonary, the first 2 patients in the series), an early stent thrombosis not requiring additional flow (PAIVS with previous valvulotomy, with improvement in pulmonary flow), and 1 case of straightening of the aortic end of the stent, that interfered with the aortic wall and required surgical removal.

Surgical shunts were created in 2 patients with tricuspid atresia who underwent ductus stenting as neonates, because ductal flow remained insufficient, and Glenn procedure was ruled out or delayed. The first of these was in a premature conjoined twin, weighing 1375g at birth, at 3 months after stenting (without previous stent dilatation). The second was in a patient who weighed 2060g at birth, at 1.8 years (after maximal stent dilatation).

Six angioplasties were performed during the period analyzed: in 2 patients with comorbidities causing a progressive increase in pulmonary pressure and consequent reduction in ductal flow, the stents were dilated to adapt to the new hemodynamics; in another, with growth, the ductus had stretched due to traction resulting in the aortic end having incomplete coverage (angioplasty with stent); in the 3 others, during surgical planning, it was decided to postpone the procedure and instead to dilate to maintain saturations in the correct range while waiting.

The median time to surgery was 195 days in the 25 patients who underwent surgery; 5 patients had a stent as their final treatment (2 pulmonary stenosis, 3 PAIVS).

Presurgical pulmonary artery branch growth was favorable, increasing from a Nakata index of 123 to 256 mm2/m2; on bivariate analysis with the Student t-test, the P value was < .01.

In conclusion, stenting of ductus arteriosus in patients with congenital heart disease and duct-dependent pulmonary flow is a safe technique with a success rate in our series of 100% in all situations after 2014. The procedure is well tolerated by patients, has short intubation times and ICU stays, and allows good branch development and the option to adjust flow to the initial situation with subsequently dilatation if the surgical plan or hemodynamic situation changes. Our recent mortality and morbidity (0% and 8%) compare well with the reported rates from the international registry of surgical shunts (7.2% and 13.1%)5 and are in line with publications from other authors.6 Currently, the technical improvements and standardization of the procedure give reproducible results, allowing ductal stenting to be considered as a first-line option for all patients who have congenital heart disease with duct-dependent pulmonary flow and need for additional pulmonary flow.