Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT) or Rendu-Osler-Weber syndrome is a rare autosomal dominant vascular disorder caused by mutations in the endoglin, ACVRL1 or SMAD4 genes that encode proteins involved in the transforming growth factor-beta superfamily, resulting in multiorgan vascular dysplasia. Clinical manifestations include spontaneous epistaxis, gastrointestinal bleeding, anemia, mucocutaneous telangiectasia, and multiorgan arteriovenous malformations.1

Cardiovascular involvement encompasses high-output heart failure, paradoxical emboli, and venous thromboembolism. Arrhythmias are common, whereas myocardial infarction rates appear to be low.1,2

Coronary angiography (CA) and percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) in patients with HHT can be challenging in terms of the underlying coronary anatomy (atheromatosis, spontaneous coronary artery dissection [SCAD], and spasm), technical aspects, antithrombotic therapy, and increased bleeding risk.2–4 We sought to assess the potential risks of CA and PCI in HHT patients by identifying retrospectively all HHT patients undergoing CA in the University Hospitals of Leuven between January 2002 and July 2017.

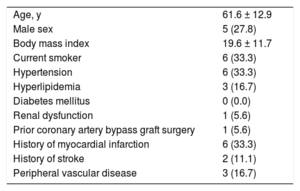

During this 15-year period, 655 HHT patients were followed up in our tertiary referral center and 18 underwent a CA. A full list of baseline characteristics is summarized in the Table. Six patients (33.3%) underwent CA due to an acute coronary syndrome (ACS), 2 patients (11.1%) due to stable angina, 5 (27.7%) due to heart failure, 3 (16.6%) due to valvular disease, and 2 (11.1%) as part of pretransplant work-up. Thirteen patients (72.2%) had normal coronaries whereas 5 (27.8%) had abnormal findings. Coronary artery disease was noted in 2 patients (11.1%), 1 presenting with a ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) treated with a bare-metal stent in the left anterior descending (LAD) and 1 with unstable angina treated with a bare-metal stent in the right coronary artery. Three patients (16.7%) exhibited SCAD of the LAD, 1 presenting as a STEMI treated with a drug-eluting stent and 2 as a non-STEMI treated conservatively. One ACS presenter had normal coronaries. Periprocedural complications occurred in 3 patients (16.6%), all ACS presenters. Accordingly, 3 out of 6 HHT patients (50%) undergoing CA in the context of an ACS had a major periprocedural complication, 2 of which occurred during PCI.

Baseline Characteristics (n = 18)

| Age, y | 61.6 ± 12.9 |

| Male sex | 5 (27.8) |

| Body mass index | 19.6 ± 11.7 |

| Current smoker | 6 (33.3) |

| Hypertension | 6 (33.3) |

| Hyperlipidemia | 3 (16.7) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0 (0.0) |

| Renal dysfunction | 1 (5.6) |

| Prior coronary artery bypass graft surgery | 1 (5.6) |

| History of myocardial infarction | 6 (33.3) |

| History of stroke | 2 (11.1) |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 3 (16.7) |

Values are expressed as mean ± standard deviation or No. (%). Renal dysfunction was defined as serum glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) < 60mL/min/1.73 m2.

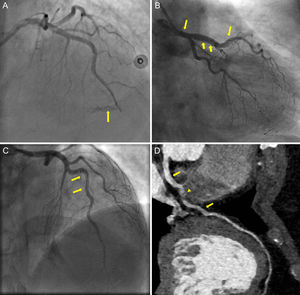

The first patient, a 67-year old man presenting with unstable angina, experienced a type-D dissection with a spiral luminal filling defect during PCI of the right coronary artery, which was treated with a bare-metal stent. The second patient, a 73-year old woman, presented with a STEMI and CA showed SCAD with TIMI flow 0 in the LAD. Predilatation with an undersized balloon, resulted in mid-LAD perforation (Figure A, arrow), which was successfully sealed with prolonged balloon inflation and was subsequently stented with a drug-eluting stent. The patient was treated with aspirin and ticagrelor. A few hours later, she showed massive gastrointestinal and pericardial bleeding leading to death. The third patient, a 47-year old woman, presented with a non-STEMI and urgent CA revealed a SCAD in the mid-LAD. With contrast injections, the dissection propagated retrograde to involve the left main (Figure B and C, arrows). As the patient remained hemodynamically stable, we opted for conservative medical treatment with dual antiplatelet therapy. During follow-up, she was asymptomatic, although a computed tomography CA at 3-months demonstrated a residual intimal flap extending from the left main to mid-LAD (Figure D, arrows) with intramural hematoma causing minimal stenosis in mid-LAD (Figure D, arrowhead).

Coronary angiography showing mid-LAD perforation (panel A, arrow). Dissection flap extending from mid-LAD up to the left main illustrated in CA (panel B, C, arrows) and in computed tomography CA (panel D, arrows), with intramural hematoma causing minimal stenosis in mid-LAD (panel D, arrowhead). CA, coronary angiography; LAD, left anterior descending.

Our data stress that CA is rarely needed in HHT patients (2.7%). In a population of 1025 HHT patients, Shovlin et al.1 reported a low rate of myocardial infarction and abnormal CA of 2.2% and < 54%, respectively, while our data demonstrate even lower rates of 0.9% and 27.8%, respectively. Nevertheless, reports have suggested that the underlying coronary anatomy and the procedural hazards can complicate CA and PCI in these patients.2–4 In particular, apart from atherosclerotic lesions, other causes of myocardial infarction have been reported, such as SCAD, endothelial dysfunction, and emboli.2–4 In our study, 50% of HHT patients presenting with an ACS had a SCAD. Additionally, 50% of ACS presenters experienced a major periprocedural complication, most of them during PCI.

Endothelial damage in HHT patients is attributed to mutations causing endothelial nitric oxide synthase uncoupling and generation of reactive oxygen species, while impaired transforming growth factor-beta signaling induces cytoskeleton disorganization and fragility of the vessel wall.5,6 Vessel wall fragility could be further aggravated by the proinflammatory milieu during an ACS, making HHT patients more vulnerable to complications during urgent CA and PCI. Additionally, such patients bear a substantial bleeding risk associated with PCI antithrombotic treatment and their inherent bleeding predisposition.1 Additional research is essential to clarify the underlying pathophysiology.

In conclusion, physicians must be alert for periprocedural pitfalls during CA and PCI in HHT patients presenting with an ACS and these should be taken into consideration in decision-making and interventional planning.