There have been no studies conducted in the past that focus on the significance of congestive heart failure in patients with prosthetic valve endocarditis. We studied the incidence of congestive heart failure in patients with prosthetic valve endocarditis and analyzed its profile. In this study, we addressed the prognostic significance of heart failure in patients with prosthetic valve endocarditis and analyzed its outcome based on chosen therapeutic strategies.

MethodsA total of 639 episodes of definite left-sided endocarditis were prospectively enrolled. Of them, 257 were prosthetic. Of the 257 episodes, 145 (56%) were diagnosed with heart failure. We compared the profiles of patients with prosthetic valve endocarditis based on the presence of heart failure, and performed a multivariate logistic regression model to establish the prognostic significance of heart failure in patients with prosthetic valve endocarditis and identified the prognostic factors of in-hospital mortality in these patients.

ResultsPersistent infection (odds ratio=3.6; 95% confidence interval, 1.9-6.9) and heart failure (odds ratio=3; 95% confidence interval, 1.5-5.8) are the strongest predictive factors of in-hospital mortality in patients with prosthetic valve endocarditis. The short-term determinants of prognosis in patients with prosthetic valve endocarditis and heart failure are persistent infection (odds ratio=2.8; 95% confidence interval, 1.2-6.5), aortic involvement (odds ratio=2.5; 95% confidence interval, 1.1-5.8), abscess (odds ratio=3.6; 95% confidence interval, 1.4-9.5), diabetes mellitus (odds ratio=2.9; 95% confidence interval, 1.1-7.7), and cardiac surgery (odds ratio=0.2; 95% confidence interval, 0.1-0.5).

ConclusionsThe incidence of heart failure in patients with prosthetic valve endocarditis is very high. Heart failure increases the risk of in-hospital mortality by threefold in patients with prosthetic valve endocarditis. Persistent infection, aortic involvement, abscess, and diabetes mellitus are the independent risk factors associated with mortality in patients with prosthetic valve endocarditis and heart failure; however, cardiac surgery is shown to decrease mortality in these patients.

Keywords

.

INTRODUCTIONDespite major advances in cardiovascular surgical techniques and the routine use of prophylactic antimicrobial agents, prosthetic valve endocarditis (PVE) continues to complicate the course of a small percentage of patients after cardiac valve replacement. The prognosis of PVE is grim, especially when cardiac and extracardiac complications occur.1,2 One of the most dreaded complications arising from PVE is congestive heart failure (CHF), which is the most frequent indication for early surgery3 and has been identified as an independent risk factor for early and late mortality in patients with native valve endocarditis4 and PVE.2,5,6

There is scant data in past literature that specifically addresses the significance of CHF in PVE. The importance of CHF as a prognostic factor and the identification of the best therapeutic approach towards its treatment are key issues for clinicians involved in the management of patients diagnosed with this challenging condition.

This study represents the widest series to date with the largest study population, which specifically analyzes the incidence and causes of CHF in patients with PVE. The study describes the profile of CHF in these patients, identifies prognostic factors associated with its development, addresses its prognostic significance, and analyzes clinical outcomes based on chosen therapeutic strategies.

Definitions of TermsCHF was diagnosed by a team of experts in accordance with the Framingham criteria7; its severity was assessed according to the New York Heart Association (NYHA) classification.

Our methodology and the definitions of terms used in this study have already been explained in previous manuscripts.8–10 Surgical indications were agreed upon by a common consensus among the researchers and included CHF refractory to medical treatment, fungal endocarditis, recurrent embolism with persistent vegetations in the echocardiogram, and uncontrolled infection defined as “persistent bacteremia or fever persisting for more than 7 days despite appropriate antibiotic treatment, once other foci of infection have been ruled out”. The clinical criteria to operate or not to operate, was the same in all groups. When a patient with surgical criteria did not undergo surgery, it was either because the patient rejected the intervention, the surgical risk was too high, or because the patient was too fragile. In all cases, the final decision was made by a multidisciplinary team of cardiologists, cardiac surgeons, microbiologists, and specialists in infective diseases. Early PVE was defined as that which occurred less than 1 year after surgery.10

METHODSPatients included in the analysis were enrolled from 3 university-affiliated tertiary care hospitals; these were the referral centers for their regions on infective endocarditis. All the hospitals worked together using standardized protocols, uniform data collection, and uniform diagnostic and therapeutic criteria from the beginning of the study.

From 1996 to 2009, 639 episodes of definite left-sided infective endocarditis in 619 patients were prospectively enrolled for the study; Duke criteria were applied until the year 200211 and modified Duke criteria were applied thereafter.12 Of these 639 episodes, 257 (40%) were PVE and constituted the study group.

Statistical AnalysisCategorical variables are reported as absolute values and percentages. Continuous variables are expressed as mean (standard deviation) or median [interquartile range]. Normal distribution of quantitative variables was verified with the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Qualitative variables were compared with the chi-square test and Fisher's exact test. Continuous variables were compared with Student t test or its equivalent for nonparametric tests, and Mann-Whitney's U test was used for variables that were not normally distributed.

To identify factors that were predictive of mortality, we constructed a logistic regression model with the maximum likelihood method using backwards stepwise selection, which included the variables that were statistically significant in the bivariate analysis. No more than 1 variable per 10 outcome events was entered in the logistic model to avoid overfitting. For the final model, we calculated odds ratios (OR) adjusted for each of the variables included, along with their 95% confidence intervals (95%CI). Goodness of fit for each model was determined with the Hosmer-Lemershow test and C-index.

A P<.05 was used as a cutoff for statistical significance. Data was analyzed using the SPSS V15.0 software package (SPSS; Chicago, Illinois, United States).

The authors have full access to and take full responsibility for the integrity of the data reported in this manuscript. All authors have read the manuscript and mutually agree with the format in which the manuscript has been written.

RESULTSAmong 257 patients with PVE in our series, 145 patients (56%) were diagnosed of CHF: 115 patients (79%) had CHF at the time of admission, (58% patients from NYHA functional class III or IV) and the remaining 30 patients (21%) developed CHF during their hospital stay.

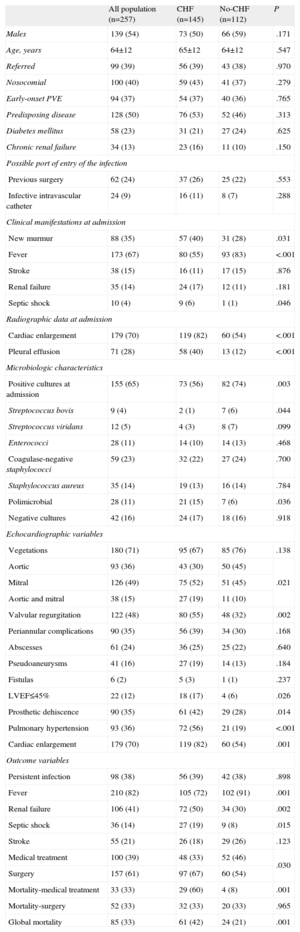

Baseline CharacteristicsA total of 96 variables were recorded in every patient (Appendix). The results from this analysis are summarized in Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Patients With Prosthetic Valve Endocarditis Complicated With Congestive Heart Failure Compared to Patients Without Congestive Heart Failure

| All population (n=257) | CHF (n=145) | No-CHF (n=112) | P | |

| Males | 139 (54) | 73 (50) | 66 (59) | .171 |

| Age, years | 64±12 | 65±12 | 64±12 | .547 |

| Referred | 99 (39) | 56 (39) | 43 (38) | .970 |

| Nosocomial | 100 (40) | 59 (43) | 41 (37) | .279 |

| Early-onset PVE | 94 (37) | 54 (37) | 40 (36) | .765 |

| Predisposing disease | 128 (50) | 76 (53) | 52 (46) | .313 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 58 (23) | 31 (21) | 27 (24) | .625 |

| Chronic renal failure | 34 (13) | 23 (16) | 11 (10) | .150 |

| Possible port of entry of the infection | ||||

| Previous surgery | 62 (24) | 37 (26) | 25 (22) | .553 |

| Infective intravascular catheter | 24 (9) | 16 (11) | 8 (7) | .288 |

| Clinical manifestations at admission | ||||

| New murmur | 88 (35) | 57 (40) | 31 (28) | .031 |

| Fever | 173 (67) | 80 (55) | 93 (83) | <.001 |

| Stroke | 38 (15) | 16 (11) | 17 (15) | .876 |

| Renal failure | 35 (14) | 24 (17) | 12 (11) | .181 |

| Septic shock | 10 (4) | 9 (6) | 1 (1) | .046 |

| Radiographic data at admission | ||||

| Cardiac enlargement | 179 (70) | 119 (82) | 60 (54) | <.001 |

| Pleural effusion | 71 (28) | 58 (40) | 13 (12) | <.001 |

| Microbiologic characteristics | ||||

| Positive cultures at admission | 155 (65) | 73 (56) | 82 (74) | .003 |

| Streptococcus bovis | 9 (4) | 2 (1) | 7 (6) | .044 |

| Streptococcus viridans | 12 (5) | 4 (3) | 8 (7) | .099 |

| Enterococci | 28 (11) | 14 (10) | 14 (13) | .468 |

| Coagulase-negative staphylococci | 59 (23) | 32 (22) | 27 (24) | .700 |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 35 (14) | 19 (13) | 16 (14) | .784 |

| Polimicrobial | 28 (11) | 21 (15) | 7 (6) | .036 |

| Negative cultures | 42 (16) | 24 (17) | 18 (16) | .918 |

| Echocardiographic variables | ||||

| Vegetations | 180 (71) | 95 (67) | 85 (76) | .138 |

| Aortic | 93 (36) | 43 (30) | 50 (45) | .021 |

| Mitral | 126 (49) | 75 (52) | 51 (45) | |

| Aortic and mitral | 38 (15) | 27 (19) | 11 (10) | |

| Valvular regurgitation | 122 (48) | 80 (55) | 48 (32) | .002 |

| Periannular complications | 90 (35) | 56 (39) | 34 (30) | .168 |

| Abscesses | 61 (24) | 36 (25) | 25 (22) | .640 |

| Pseudoaneurysms | 41 (16) | 27 (19) | 14 (13) | .184 |

| Fistulas | 6 (2) | 5 (3) | 1 (1) | .237 |

| LVEF≤45% | 22 (12) | 18 (17) | 4 (6) | .026 |

| Prosthetic dehiscence | 90 (35) | 61 (42) | 29 (28) | .014 |

| Pulmonary hypertension | 93 (36) | 72 (56) | 21 (19) | <.001 |

| Cardiac enlargement | 179 (70) | 119 (82) | 60 (54) | .001 |

| Outcome variables | ||||

| Persistent infection | 98 (38) | 56 (39) | 42 (38) | .898 |

| Fever | 210 (82) | 105 (72) | 102 (91) | .001 |

| Renal failure | 106 (41) | 72 (50) | 34 (30) | .002 |

| Septic shock | 36 (14) | 27 (19) | 9 (8) | .015 |

| Stroke | 55 (21) | 26 (18) | 29 (26) | .123 |

| Medical treatment | 100 (39) | 48 (33) | 52 (46) | .030 |

| Surgery | 157 (61) | 97 (67) | 60 (54) | |

| Mortality-medical treatment | 33 (33) | 29 (60) | 4 (8) | .001 |

| Mortality-surgery | 52 (33) | 32 (33) | 20 (33) | .965 |

| Global mortality | 85 (33) | 61 (42) | 24 (21) | .001 |

CHF, congestive heart failure; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; PVE, prosthetic valve endocarditis.

Data are expressed as no. (%) or mean±standard deviation.

Table 1 shows the results of univariate analyses, comparing the main characteristics of patients with and without CHF during hospitalization for infective endocarditis. The presence of new murmur, septic shock, renal failure, polimicrobial endocarditis, multivalvular and mitral involvement, left-ventricular dysfunction, pulmonary hypertension, prosthetic dehiscence, moderate or severe regurgitation, cardiac enlargement, and pleural effusion were more frequently observed in patients with CHF, whereas streptococcus bovis, fever, and positive cultures at admission were less frequent in this group of patients. Besides, patients with CHF underwent surgery more frequently. In-hospital mortality was higher in those patients who received isolated antibiotic treatment.

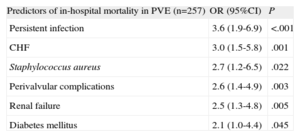

Prognostic Factors of In-hospital Mortality in Patients With Prosthetic Valve EndocarditisTo determine the influence of CHF in the prognosis of patients with PVE, we performed a univariate and a multivariate logistic regression model. The results from the multivariate analysis are summarized in Table 2. Patients with PVE complicated with CHF showed a threefold increase in the risk of mortality as compared to PVE patients without CHF. The Hosmer–Lemershow goodness-of-fit test yielded a P=.57. Calculation of model discrimination by using the concordance index was 0.80 (C-index 95%, 0.75-0.86).

Logistic Regression Model to Determine Predictors of Mortality in Patients With Prosthetic Valve Endocarditis

| Predictors of in-hospital mortality in PVE (n=257) | OR (95%CI) | P |

| Persistent infection | 3.6 (1.9-6.9) | <.001 |

| CHF | 3.0 (1.5-5.8) | .001 |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 2.7 (1.2-6.5) | .022 |

| Perivalvular complications | 2.6 (1.4-4.9) | .003 |

| Renal failure | 2.5 (1.3-4.8) | .005 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 2.1 (1.0-4.4) | .045 |

95%CI, 95% confidence interval; CHF, congestive heart failure; OR, odds ratio; PVE, prosthetic valve endocarditis.

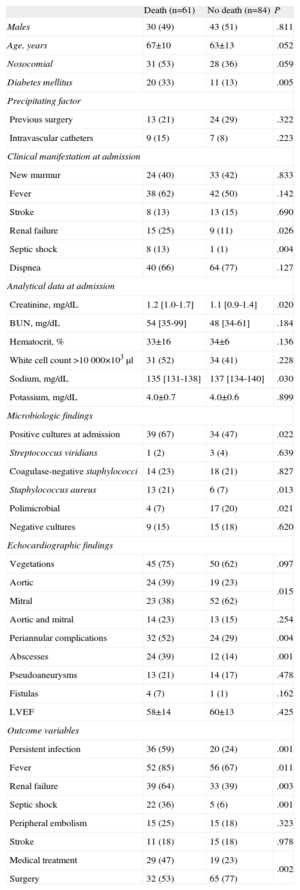

We analyzed a total of 96 variables to determine the risk factors associated with mortality in patients with PVE and CHF. The results from the univariate analysis are summarized in Table 3. Renal failure, fever, persistent infection, creatinine and sodium levels at admission, septic shock, positive blood cultures at admission, Staphylococcus aureus, diabetes mellitus, aortic involvement, and abscess were associated with higher mortality in patients with PVE and CHF. In contrast, cardiac surgery, valvular estenosis, and polimicrobial infection were associated with a better clinical outcome.

Association Between Baseline Characteristics of Congestive Heart Failure Patients and In-hospital Mortality

| Death (n=61) | No death (n=84) | P | |

| Males | 30 (49) | 43 (51) | .811 |

| Age, years | 67±10 | 63±13 | .052 |

| Nosocomial | 31 (53) | 28 (36) | .059 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 20 (33) | 11 (13) | .005 |

| Precipitating factor | |||

| Previous surgery | 13 (21) | 24 (29) | .322 |

| Intravascular catheters | 9 (15) | 7 (8) | .223 |

| Clinical manifestation at admission | |||

| New murmur | 24 (40) | 33 (42) | .833 |

| Fever | 38 (62) | 42 (50) | .142 |

| Stroke | 8 (13) | 13 (15) | .690 |

| Renal failure | 15 (25) | 9 (11) | .026 |

| Septic shock | 8 (13) | 1 (1) | .004 |

| Dispnea | 40 (66) | 64 (77) | .127 |

| Analytical data at admission | |||

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 1.2 [1.0-1.7] | 1.1 [0.9-1.4] | .020 |

| BUN, mg/dL | 54 [35-99] | 48 [34-61] | .184 |

| Hematocrit, % | 33±16 | 34±6 | .136 |

| White cell count >10 000×103μl | 31 (52) | 34 (41) | .228 |

| Sodium, mg/dL | 135 [131-138] | 137 [134-140] | .030 |

| Potassium, mg/dL | 4.0±0.7 | 4.0±0.6 | .899 |

| Microbiologic findings | |||

| Positive cultures at admission | 39 (67) | 34 (47) | .022 |

| Streptococcus viridians | 1 (2) | 3 (4) | .639 |

| Coagulase-negative staphylococci | 14 (23) | 18 (21) | .827 |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 13 (21) | 6 (7) | .013 |

| Polimicrobial | 4 (7) | 17 (20) | .021 |

| Negative cultures | 9 (15) | 15 (18) | .620 |

| Echocardiographic findings | |||

| Vegetations | 45 (75) | 50 (62) | .097 |

| Aortic | 24 (39) | 19 (23) | .015 |

| Mitral | 23 (38) | 52 (62) | |

| Aortic and mitral | 14 (23) | 13 (15) | .254 |

| Periannular complications | 32 (52) | 24 (29) | .004 |

| Abscesses | 24 (39) | 12 (14) | .001 |

| Pseudoaneurysms | 13 (21) | 14 (17) | .478 |

| Fistulas | 4 (7) | 1 (1) | .162 |

| LVEF | 58±14 | 60±13 | .425 |

| Outcome variables | |||

| Persistent infection | 36 (59) | 20 (24) | .001 |

| Fever | 52 (85) | 56 (67) | .011 |

| Renal failure | 39 (64) | 33 (39) | .003 |

| Septic shock | 22 (36) | 5 (6) | .001 |

| Peripheral embolism | 15 (25) | 15 (18) | .323 |

| Stroke | 11 (18) | 15 (18) | .978 |

| Medical treatment | 29 (47) | 19 (23) | .002 |

| Surgery | 32 (53) | 65 (77) | |

BUN, blood urea nitrogen; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction.

Data are expressed as no. (%), mean±standard deviation or median [interquartile range].

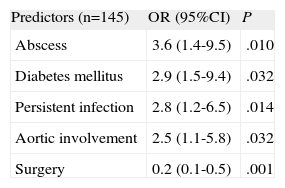

The results of multivariate analysis are summarized in Table 4. Abscess (OR=3.6; 95%CI, 1.4-9.5), diabetes mellitus (OR=2.9; 95%CI, 1.1-7.7), aortic involvement (OR=2.5; 95%CI, 1.1-5.8), and persistent infection (OR=2.8; 95%CI, 1.2-6.5) were independent predictors of in-hospital mortality in patients with PVE. On the other hand, cardiac surgery was shown to decrease mortality in these patients (OR=0.2; 95%CI, 0.1-0.5) The Hosmer–Lemershow goodness-of-fit test yielded a P=.94. Calculation of model discrimination by using the concordance index was 0.82 (C-index 95%, 0.75-0.89).

Logistic Regression Model to Determine Predictors of Mortality in Patients With Prosthetic Valve Endocarditis Complicated With Congestive Heart Failure

| Predictors (n=145) | OR (95%CI) | P |

| Abscess | 3.6 (1.4-9.5) | .010 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 2.9 (1.5-9.4) | .032 |

| Persistent infection | 2.8 (1.2-6.5) | .014 |

| Aortic involvement | 2.5 (1.1-5.8) | .032 |

| Surgery | 0.2 (0.1-0.5) | .001 |

95%CI, 95% confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

Despite the fact that the development of CHF in patients with PVE is a crucial aspect in the prognosis of these patients, there is a lack of studies in previous literature that specifically address this issue. Very important aspects of this entity, as its incidence and its influence on the prognosis or predictors of mortality, remain unknown. This study, that represents the widest series to date which specifically analyzes CHF in patients with PVE, has shed some light on these unknown aspects.

Several consequences can be drawn from this study. First, the incidence of CHF among patients with PVE is very high, accounting for more than 50% of these patients. Second, the mortality of PVE complicated with CHF is very high, especially in patients who receive medical treatment alone. Third, CHF is an independent risk factor associated with PVE, which increases the risk of in-hospital mortality in patients by threefold. And fourth, persistent infection, aortic involvement, abscess, and diabetes mellitus are the independent risk factors associated with mortality in patients with PVE and CHF. On the other hand, cardiac surgery is shown to decrease mortality in patients with PVE and CHF.

To the best of our knowledge, the incidence of CHF is the highest in our series of patients with PVE. Several reasons might explain this finding: expert teams on heart failure were responsible for these patients and these teams followed the most universally accepted criteria for the diagnosis of CHF-the Framingham criteria. Also, the aggressive microbiological profile of our series, with a high proportion of infections caused by staphylococci species may explain the high incidence of CHF in this study. Finally, in contrast to other studies, we included patients with CHF from all NYHA functional classes, not just NYHA functional classes III and IV.13

Our results suggest that cardiac surgery decreases mortality in patients with PVE and CHF. This finding must be interpreted with some caution, as surgery is very often denied in these patients because of the high operative risk involved in cardiac surgery and also because this subgroup of patients has the worst prognosis.14 This phenomenon is probably more frequent in PVE than in native valve endocarditis, as the patients are usually older in PVE cases and have at least 1 previous cardiac intervention. Only randomized studies can demonstrate whether early surgery actually improves the prognosis of these patients.15 Nonetheless, our data reinforces what the guidelines recommend; that the best therapeutic option for patients with PVE and CHF is cardiac surgery.13–16

From a clinical point of view, the identification of high-risk subgroups of patients based on the presence of prognostic markers is very important in both native valve endocarditis and PVE, because it helps us to decide the best therapeutic approach for these patients. Several predictive factors of mortality in patients with PVE have been identified in previous studies17: increasing age, severe comorbidity, persistent bacteremia, health care associated infection, S. aureus, early onset PVE, renal failure, mediastinitis, complicated PVE, abscesses, cerebral complications, CHF, and septic shock. Among them, staphylococcal infections and CHF are the most constant variables. Our results corroborate these findings, and include diabetes mellitus as an important prognostic marker of in-hospital mortality in PVE. Some previous studies that have attempted to identify risk factors in patients with PVE are now outdated,18–20 as these studies analyzed only a specific subgroup of patients with PVE,18–21 included only a few patients,19,21 or came from single institutions.18–22 The international-collaboration-on-endocarditis group reported 556 patients with PVE from 63 centers in 28 countries.2 They reported older age, health care-associated infection, S. aureus, CHF, stroke, intracardiac abscesses, and persistent bacteremia as predictive factors of in-hospital mortality in patients with PVE. In their study, diabetes mellitus did not reach statistically significant differences and renal failure was not analyzed.

Once it was established that CHF worsens the prognosis of patients with PVE, we further investigated what factors help in identifying high-risk patients with PVE and CHF. The 4 independent risk factors identified in our series have already been described in previous studies.2,5,23,24 The most powerful predictor of mortality in our series was persisting infection, which was in consonance with previous findings of our group.25 It is important to highlight that more than 70% of the PVE cases caused by S. aureus were associated with persistent infection, which explains why this microorganism did not reach significance in the multivariate analysis. The role of perivalvular complications in the prognosis of infective endocarditis has been largely studied in detail and is well established.2,10 However, less uniformity in data is found regarding diabetes mellitus. In some series, diabetes mellitus was shown to increase the risk of mortality in patients with infective endocarditis,26 however, these results are not consistent with findings from other authors.27 Our results suggest that diabetes mellitus may be associated with increased risk when the infectious process affects prosthesis. Mechanisms proposed in previous literature relate to depression in the leukocyte chemotaxis, adherence, phagocytosis, intracellular killing, and opsonization.26

LimitationsWe are aware of several limitations of our work. We did not use biochemical markers such as brain natriuretic peptide or the amino terminal portion of the pro-hormone in the diagnostic and prognostic evaluation of patients with CHF because it was not available throughout the study in our hospitals. Increased plasma levels of natriuretic peptide and the amino terminal portion of the pro-hormone have been identified as predictors of cardiac dysfunction and death in many critical care settings, including heart failure, myocardial infarction, and septic shock. There is only 1 small study in which increased levels of natriuretic peptide hormones at admission were found to be predictive of in-hospital mortality or urgent surgery in patients with infective endocarditis.28 Nonetheless, these findings need to be validated in larger cohorts of patients.

We did not record, in our database, possible precipitants of heart failure different from those related to the infection itself (ie, arrhythmias, acute coronary syndromes, and hypertensive emergency) or conditions prone to the development of CHF (ie, coronary heart disease, left ventricular hypertrophy, etc.).

CONCLUSIONSFinally, this study was done at tertiary hospitals, a setting that biases the type of patients included in our database. Our sample does not reflect the characteristics of all patients with infective endocarditis in the general population, but rather the population of patients with PVE admitted to dedicated hospitals. Accordingly, our conclusions are applicable to reference hospitals equipped and staffed to perform heart surgery. All observational studies, as well as many randomized studies, have built-in bias.29 Effects of referral bias in tertiary care centers have been previously acknowledged in endocarditis30 and in surgical outcomes.31 It cannot be avoided but it must be recognized. In our population of patients with PVE, mortality may be higher than that observed in a population-based cohort because patients may have died before they are sent to our hospital. On the contrary, mortality may be lower because patients with a favourable clinical course may not be sent to our hospital. However, our results are comparable to other series coming from tertiary centers, where majority of the research in infective endocarditis has been performed.

FundingThe present study was partly financed by the Cooperative Cardiovascular Disease Research Network and was supported by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III in Spain.

Conflicts of InterestNone declared.

We thank Ana Puerto for her statistical advice.

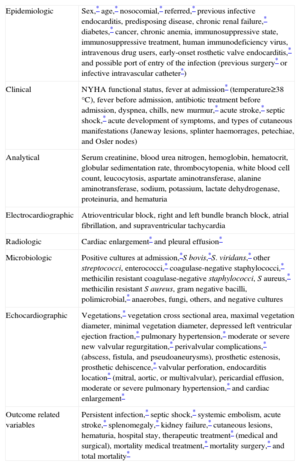

| Epidemiologic | Sex,* age,* nosocomial,* referred,* previous infective endocarditis, predisposing disease, chronic renal failure,* diabetes,* cancer, chronic anemia, immunosuppressive state, immunosuppressive treatment, human immunodeficiency virus, intravenous drug users, early-onset rosthetic valve endocarditis,* and possible port of entry of the infection (previous surgery* or infective intravascular catheter*) |

| Clinical | NYHA functional status, fever at admission* (temperature≥38°C), fever before admission, antibiotic treatment before admission, dyspnea, chills, new murmur,* acute stroke,* septic shock,* acute development of symptoms, and types of cutaneous manifestations (Janeway lesions, splinter haemorrages, petechiae, and Osler nodes) |

| Analytical | Serum creatinine, blood urea nitrogen, hemoglobin, hematocrit, globular sedimentation rate, thrombocytopenia, white blood cell count, leucocytosis, aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, sodium, potassium, lactate dehydrogenase, proteinuria, and hematuria |

| Electrocardiographic | Atrioventricular block, right and left bundle branch block, atrial fibrillation, and supraventricular tachycardia |

| Radiologic | Cardiac enlargement* and pleural effusion* |

| Microbiologic | Positive cultures at admission,*S bovis,*S. viridans,* other streptococci, enterococci,* coagulase-negative staphylococci,* methicilin resistant coagulase-negative staphylococci, S aureus,* methicilin resistant S aureus, gram negative bacilli, polimicrobial,* anaerobes, fungi, others, and negative cultures |

| Echocardiographic | Vegetations,* vegetation cross sectional area, maximal vegetation diameter, minimal vegetation diameter, depressed left ventricular ejection fraction,* pulmonary hypertension,* moderate or severe new valvular regurgitation,* perivalvular complications,* (abscess, fistula, and pseudoaneurysms), prosthetic estenosis, prosthetic dehiscence,* valvular perforation, endocarditis location* (mitral, aortic, or multivalvular), pericardial effusion, moderate or severe pulmonary hypertension,* and cardiac enlargement* |

| Outcome related variables | Persistent infection,* septic shock,* systemic embolism, acute stroke,* splenomegaly,* kidney failure,* cutaneous lesions, hematuria, hospital stay, therapeutic treatment* (medical and surgical), mortality medical treatment,* mortality surgery,* and total mortality* |

NYHA, New York Heart Association.