Although cardiovascular (CV) mortality has declined in recent years, it remains the leading cause of death and accounts for 29.66% of all mortality in Spain.1 However, mortality rates are not the same in the different regions of Spain. For example, Andalusia has the highest mortality rate (33.16%) and the Canary Islands the lowest (24.34%). The differences in prevalence, degree of control and prevention of CV risk factors, and socioeconomic status are the proposed main drivers behind these differences.2

The objective of this study was to analyze CV mortality and other CV indicators and to establish their relationship with gross domestic product (GDP) per capita (indicator of wealth) in the different regions of Spain between 2005 and 2014. The variables collected are shown in Table 1, Table 2, and Table 3 of the supplementary material. The data were derived from the mean values for each year of the 10-year study period, expressed per million inhabitants and standardized by age and sex.

Mortality data and GDP per Capita were obtained from the Spanish National Statistics Institute. CV interventions were taken from the Spanish Society of Cardiology, the Andalusian Society of Cardiology, and the Spanish Society of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery.

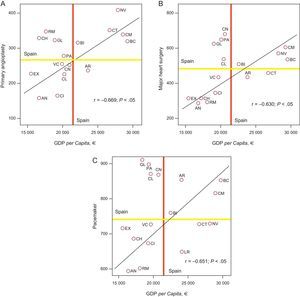

The GDP per Capita data can be found in Table 1 of the supplementary material. The analysis showed a significant correlation between lower GDP and higher CV mortality in general, mortality associated with ischemic heart disease, and mortality associated with cerebrovascular disease (Figure 1), and between lower GDP and a lower number of primary angioplasty procedures, major cardiac surgery, and pacemaker placement (Figure 2). The remaining variables were not significant.

Correlation between gross domestic product per capita of the different regions of Spain and overall cardiovascular mortality (A), ischemic heart disease (B), and stroke (C). The regions are identified with initials and mortality data are expressed as the number of deaths and gross domestic product per capita in € (mean data from 2005 to 2014 per million inhabitants and standardized for age and sex). AN, Andalusia; AR, Aragon; BC, Basque Country; BI, Balearic Islands; CI, Canary Islands; CH, Castile-La Mancha; CL, Castile and Léon; CM, Community of Madrid; CN, Cantabria; CT, Catalonia; EX, Extremadura; GDP, gross domestic product; GL, Galicia; LR, La Rioja; NV, Navarre; PA, Principality of Asturias; RM, Region of Murcia; VC, Valencian Community.

Correlation between gross domestic product per Capita of the different regions of Spain and rate of primary angioplasty (A), major cardiac surgery (B), and pacemakers (C). The regions are identified with initials. The gross domestic product per capita is expressed in €. The data were derived from the mean values for each year of the period 2005 to 2014, expressed per million inhabitants and standardized by age and sex. AN, Andalusia; AR, Aragon; BC, Basque Country; BI, Balearic Islands; CI, Canary Islands; CH, Castile-La Mancha; CL, Castile and Léon; CM, Community of Madrid; CN, Cantabria; CT, Catalonia; EX, Extremadura; GDP, gross domestic product; GL, Galicia; LR, La Rioja; NV, Navarre; PA, Principality of Asturias; RM, Region of Murcia; VC, Valencian Community.

It is known that the prevalence of the main CV risk factors differ from region to region within a country and between countries. The regions in the south of Spain have the highest prevalence. The prevalences of obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus, among other conditions, appear to be the main drivers of these differences. Both these factors are closely associated with lifestyle and socioeconomic factors.1,3 This suggests that regions with a lower socioeconomic status may be at greater CV risk, not only because of higher prevalence of CV risk factors but also because of a lower degree of control and prevention of these factors and greater barriers to accessing the health system.4 In this study, Andalusia is particularly noteworthy. This is one of the poorest regions and has the highest rates of mortality and, paradoxically, the highest rates of CV procedures. There are other regions with the same unfavorable factors as Andalusia in terms of the deviation from the national means (Figure 1 and Figure 2).

The CV health of a region does not just depend on socioeconomic status, given that unmodifiable factors also have an impact. However, this factor does appear to play a major role in the presence of CV risk factors and their degree of control and prevention. Wealthy societies with well-developed health services have extensive health coverage and ready access to all levels of health care. This favors the development of policies aimed at lifestyle interventions that can impact the cardiometabolic risk of the population.4

The results of this study, although subject to certain limitations given that data collection was voluntary in the centers, show that the wealth of a region should be taken into account when estimating CV risk because a correlation was found between lower GDP of a Spanish region and higher CV mortality with a lower number of procedures. These indicators could be used to help ensure appropriate resource assignment and to evaluate the success or failure of health policies.

FUNDINGL.M. Pérez-Belmonte has a Jordi Soler postqualification grant from the Cardiovascular Research Network (RIC).