To the Editor,

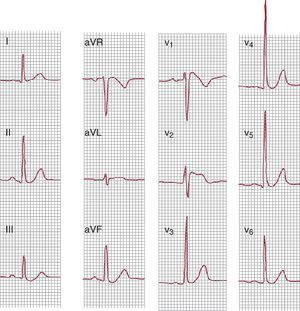

We describe a 42-year-old man with repeated use of cannabis as the only history of interest. He had come to the emergency room twice in 3 months for palpitations immediately after using moderate doses of the drug. An electrocardiogram (ECG) was performed at both visits. On the first occasion, no abnormalities were described; however, on the second, the ECG showed type I Brugada ECG pattern (BEP) (Figure 1, Figure 2) and frequent premature ventricular beats (right ventricular outflow tract morphology). The presence of fever or other situations or substances that could induce BEP was excluded. The patient was advised to cease using the drug and was referred to our clinic. The patient, remaining abstinent, presented a normal ECG in the clinic. When the V1 and V2 leads were placed in the second intercostal space, type III BEP was observed (Figure 2). The previous emergency room ECGs were reviewed, and type I BEP was found on the first occasion. The echocardiogram and Holter recording were normal.

Figure 1. Twelve-lead electrocardiogram showing type I Brugada pattern (obtained when the patient came to the emergency room after cannabis use).

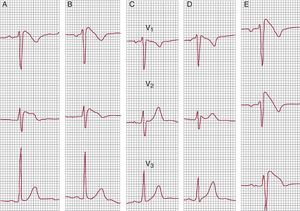

Figure 2. Electrocardiogram (V1-V3 leads). A and B, type I Brugada pattern that appeared at 2 visits in the emergency room after cannabis exposure. C and D, electrocardiogram in the outpatient clinic, no recent use. In D, the V1 and V2 leads were raised to the second intercostal space and type III Brugada pattern was observed. E, V1-V3 leads during flecainide infusion; type I Brugada pattern.

We reviewed the literature to search for any relationship between cannabis and Brugada syndrome.1, 2 We found only 1 case study which described the appearance of BEP after acute cannabis-induced intoxication in a young patient but concluded that the case did not exhibit a true Brugada pattern, as procainamide testing was negative. For this reason, we decided to carry out a flecainide test to exclude that our case was similar.

In the flecainide test, the patient presented type III BEP at baseline. The infusion was prematurely stopped when type I BEP appeared. Therefore, it was concluded that the patient presented asymptomatic BEP (in the absence of syncope, family history of sudden death, or other risk criteria), and that the BEP does not appear spontaneously, but only after cannabis exposure, hence he was a low-risk patient.

The cannabis prohibition was maintained, and at the subsequent follow-up visit, the patient had remained abstinent. There were no clinical manifestations. At a total of 4 visits following cannabis cessation, the patient showed no type I BEP (normal ECG on 2 occasions; type III pattern on 2 occasions).

Our case raises the issue of a possible interaction between cannabis and manifestations of Brugada syndrome.

It could be argued that the patient had intermittent type I BEP and that the relationship between the appearance of this pattern and prior cannabis use was fortuitous, although this is rather unlikely. Hypothetically, reproducibility of the ECG abnormalities could be confirmed by controlled exposure of the patient to cannabis. Because the drug is illegal and potentially addictive, however, the test would raise ethical and legal problems. Moreover, there is a lack of experience with the performance and interpretation of this type of experiment (necessary dose, safety, sensitivity, specificity).

An additional argument is that the literature contains no similar descriptions and the mechanisms of the interaction are unclear. A late vagotonic effect after cannabis exposure has been described, and vagal tone is one of the situations that can unmask BEP.3, 4 Cannabinoids have also been reported to block Kv1.5 cardiac potassium channels,5 although this effect does not appear to explain the appearance of BEP.

In light of the results described and until new evidence is available, we considered prudent to add cannabis to other drugs and toxic substances that should be avoided by patients with BEP at our hospital.

Corresponding author: antoniojoserp@hotmail.com