Left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) is a common finding after heart transplant (HTx)1 and is associated with a less favorable prognosis. Several variables have been related to a higher risk of severe LVH following transplant, such as patient age, obesity, prior diabetes or hypertension,1 immunosuppressive therapy, and the possible presence of a primary graft disease that manifests after transplant.

Apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy is a relatively uncommon variant, associated with increased wall thickness of the left ventricular apical segments and a reduction in the ventricular cavity.3 The symptoms are nonspecific and diagnosis is often delayed.3,4 The objective of our study was to describe the characteristics and clinical course of a cohort of patients with apical LVH following HTx.

A search was carried out in patients who had undergone HTx since 1988, in active follow-up. Apical LVH was defined by myocardial thickness> 15 mm in the apex of the left ventricle, or> 13 mm with a ratio of basal to apical segments> 1.5.5 Eight cases of apical LVH were identified in the total of 233 transplant recipients alive and under follow-up (prevalence 3.4%). Mean age at diagnosis was 56.4± 8.8 years, and there was a higher percentage of women in this group than among patients without LVH (62.5% vs 26.2%, respectively).

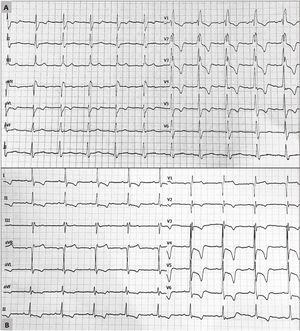

The most common reason for transplant in patients with apical LVH was dilated cardiomyopathy: 5 patients (62.5%) (table 1). None of the donor hearts showed significant LVH (on echocardiography performed in the donor's center of origin), and ventricular function was within the normal limits. Following transplant, all patients received an immunosuppressive regimen that included a calcineurin inhibitor, but in 1 case this was replaced by everolimus before the LVH diagnosis due to graft vascular disease in a patient with renal failure. In 2 other patients a change to everolimus was made after the LVH diagnosis, but no significant regression of the condition has been observed to date (1 and 2 years, respectively, of follow-up). In all cases, electrocardiograms showed a characteristic LVH pattern, with increased voltages and giant negative T waves in the precordial leads (figure 1). Cardiac magnetic resonance confirmed the diagnosis in the 4 patients who underwent this examination. Apical aneurysms were not observed in any of the patients. Two patients had “mixed” septal and apical hypertrophy, with no differences in the form of presentation or clinical course of the condition. In the follow-up endomyocardial biopsy specimens after HTx, there were no features indicating endomyocardial fibrosis, eosinophilia, or significant fibrosis.

Patients with apical ventricular hypertrophy following heart transplant

| Reason for HTx | Age at diagnosis, years | Sex | CVRF | Immunosuppression* | NYHA | GVD | History of acute rejection | Apical LVH, mm | History of atrial arrhythmias | Years since the diagnosis | Cardiac MR | BNP | NT-proBNP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ischemia | 68 | Man | Hypertension dyslipidemia diabetes | Cyclosporine+Azathioprine | II | CAV 1 | No rejection | 15 | No | 13 | — | 145 | 2481 |

| 2 | Peripartum | 46 | Woman | Hypertension | Tacrolimus+mycophenolate | I | CAV 1 | No rejection | 14 | Flutter | 8 | Apical hypertrophy, 14 mm; no delayed gadolinium enhancement | 116 | 269 |

| 3 | Peripartum | 39 | Woman | Hypertension | Tacrolimus+mycophenolate | II | CAV 0 | No rejection | 15 | No | 8 | Apical hypertrophy, 15 mm; delayed enhancement in apical mesocardium | 108 | 483 |

| 4 | Myocarditis | 71 | Man | Hypertension | Everolimus+mycophenolate+prednisone | II-III | CAV 1 | 2R | 19 | No | 3 | Apical hypertrophy up to 20mm; mesocardial enhancement in the area with greatest hypertrophy | 458 | 4390 |

| 5 | Idiopathic dilated | 65 | Man | Hypertension | Tacrolimus+mycophenolate+prednisone | II-III | CAV 0 | 2R | 23 | No | 1 | — | 384 | 17895 |

| 6 | Ischemia | 54 | Woman | Hypertension | Tacrolimus(change to everolimus)+mycophenolate | II | CAV 0 | No rejection | 19 | No | 3 | Apical hypertrophy, 18 mm; inferolateral mesocardial gadolinium enhancement | 145 | 903 |

| 7 | Ischemia | 39 | Woman | No | Tacrolimus(change to everolimus)+mycophenolate+prednisone | II | CAV 3 | No rejection | 18 | Flutter | 14 | — | 254 | 4655 |

| 8 | Idiopathic dilated | 65 | Woman | No | Tacrolimus+mycophenolate | II | CAV 0 | No rejection | 20 | No | 6 | — | 283 | 2930 |

BNP, brain natriuretic propeptide; CAV, cardiac allograft vasculopathy, nomenclature of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: CAV 0 (not significant), CAV 1 (mild), CAV 2 (moderate), and CAV 3 (severe); CVRF, cardiovascular risk factors; GVD, graft vascular disease; HTx, heart transplant; LVH, left ventricular hypertrophy; MR, magnetic resonance; NT-proBNP, amino-terminal fraction of brain natriuretic propeptide; NYHA, New York Heart Association.

Electrocardiograms showing characteristic features of apical ventricular hypertrophy in 2 patients following heart transplant. A: complete right bundle branch block with increased voltages and criteria indicating left ventricular hypertrophy. B: increased voltages with criteria of left ventricular hypertrophy and deep T-wave inversion in the precordial leads.

None of the patients with apical LVH following transplant had to be hospitalized for heart failure, malignant ventricular arrhythmias, or sudden cardiac death. The predominant symptom was exertional dyspnea, (7 patients, 87.5%). One previously reported case of LVH following HTx also had a benign clinical course.6 Among the total, only 1 patient had repeated episodes of syncope; head trauma occurring in 1 of the episodes led to intracranial bleeding and death.

Although LVH was severe in all cases, most patients in our series showed no significant clinical consequences. The most common symptom was functional class deterioration. This outcome is comparable to that of other cohorts with apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, who have shown low mortality and few adverse cardiovascular events.4,5 Although a considerable percentage of our apical LVH patients had a history of hypertension, it is unlikely that hypertension was the cause of the condition given the location of LVH and the cardiac magnetic resonance findings. The specific cause of LVH was not identified after excluding rejection and microbiological causes such as cytomegalovirus infection. Of particular note, an uncommon adverse effect of calcineurin inhibitors is LVH,2 as described in patients receiving these drugs for immunosuppressive therapy in autoimmune diseases, hematologic malignancies, and solid organ transplantation. The origin of apical LVH in our patients would likely be multifactorial, including the action of cytokines, hemodynamic overload, and possible sarcomeric cardiomyopathy in the donor that could develop later. The most important limitations of the present study are the small number of cases of apical LVH and the disparity in the length of follow-up (between 1 and 14 years).

This is the first study to date describing a consecutive series of patients with apical LVH following HTx, which is likely an underdiagnosed condition. The patients’ clinical course was benign in most cases.