Dextro-transposition of the large arteries is a cyanotic congenital heart defect characterized by ventriculoarterial discordance (the aorta is connected to the right ventricle and the pulmonary artery is connected to the left ventricle). Atrial switch surgery, described by Mustard, redirects blood flow from the venae cavae to the mitral valve and from the pulmonary veins to the tricuspid valve by means of pericardial patches. However, venous baffle stenosis and dehiscence have been observed during surgical follow-up.1

We describe our experience with the percutaneous treatment of follow-up lesions after a Mustard operation. We analyzed our patients’ general and hemodynamic variables and the percutaneous techniques used. Qualitative variables are expressed as frequency distribution and quantitative variables as mean ± standard deviation or median [interquartile range]. The corresponding statistical tests were applied (Pearson's correlation coefficient and chi-square, or Fisher exact test and Student t test).

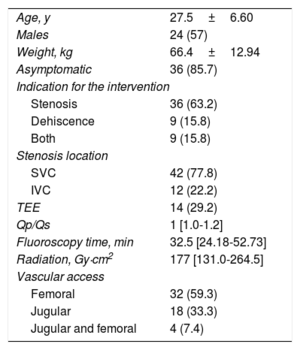

Between November 2008 and February 2017, 54 percutaneous interventions were performed in 42 patients. The patients’ general characteristics are described in Table.

Demographic Characteristics (54 Interventions in 42 Patients)

| Age, y | 27.5±6.60 |

| Males | 24 (57) |

| Weight, kg | 66.4±12.94 |

| Asymptomatic | 36 (85.7) |

| Indication for the intervention | |

| Stenosis | 36 (63.2) |

| Dehiscence | 9 (15.8) |

| Both | 9 (15.8) |

| Stenosis location | |

| SVC | 42 (77.8) |

| IVC | 12 (22.2) |

| TEE | 14 (29.2) |

| Qp/Qs | 1 [1.0-1.2] |

| Fluoroscopy time, min | 32.5 [24.18-52.73] |

| Radiation, Gy·cm2 | 177 [131.0-264.5] |

| Vascular access | |

| Femoral | 32 (59.3) |

| Jugular | 18 (33.3) |

| Jugular and femoral | 4 (7.4) |

IVC, inferior vena cava; SVC, superior vena cava; TEE, transesophageal echocardiography.

Data are expressed as No. (%), mean±standard deviation or median [interquartile range].

Reperfusion was achieved in 9 out of the 11 baffles with complete obstruction (8 in the superior vena cava [72.7%], 2 in the inferior vena cava, and 1 in both) (see video in the supplementary material). Transhepatic access was required to facilitate the intervention in 3 patients with bilateral femoral venous thrombosis. The baffle was perforated with the stiff end of a coronary guidewire (n=8) or a Nykanen radiofrequency guidewire (n=3). Sequential dilatation was then performed with angioplasty balloons and a stent was implanted (9 CP stents).

The fluoroscopy time was 58.2±24.88minutes and the radiation dose was 251 [159.0-365.0] Gy cm2.

Stenosis was observed in venous baffles in 44 patients (33 in the superior vena cava, 10 in the inferior vena cava, and 1 in both). A total of 42 stents were implanted (28 CP, 10 coated CP, and Intrastent Max, LD Max, and EV3 stents). Stent length ranged from 26mm to 45mm. The baffle lumen increased from 7±3.3mm to 14±5.7mm (P < .001). The fluoroscopy time was 32.9 [24.33-52.73] minutes and the radiation dose was 187 [131.0-264.5] Gy cm2.

We found 18 cases of baffle dehiscence, 5 of which had bidirectional shunt, but all patients had exercise-induced hypoxia. Treatment was successful in 13 cases (72.2%) and consisted of 7 coated CP stents, 5 atrial septal defect closure devices, and 1 ductus arteriosus closure device. The fluoroscopy time was 32.9 [24.45-50.30] minutes and the radiation dose was 179 [133.0-270.8] Gy cm2.

There were 9 complications: atrial flutter (n=2), pacemaker lead dysfunction after stent implantation (n=3), and minor complications (pseudoaneurysm, femoral arteriovenous fistula, neuroapraxia, mild pleural effusion, and inguinal hematoma). All complications were resolved satisfactorily and there was no procedural mortality.

The follow-up time was 2.8±1.84 (maximum, 8.4) years, and no baffle restenosis or stent fractures were observed on X-ray or echocardiography during follow-up. All patients received antiplatelet therapy with aspirin, without complications.

A total of 14 patients (33.3%) had pacemakers: 9 had stenosis of the superior baffle that required stent implantation jailing of the pacemaker leads; in 3 patients a lead dysfunction was observed, and a replacement was required in 1 patient.

Our study is the largest series of percutaneous interventions in patients with Mustard operations published to date. In 2012, Hill et al.2 described 29 interventions in 22 patients with Mustard operations and found superior vena cava obstruction in 72%, including 5 patients who had complete superior venous canal obstruction and underwent perforation with the stiff end of a guide or with a transseptal needle. Patients with pacemakers had the lead extracted before the stent was implanted in the superior vena cava.

Another recent study has described interventions performed in a series of 20 patients with atrial switch.3 A radiofrequency guidewire was used in 2 patients with complete obstruction where dehiscence was a complication. In 2 patients, a stent was implanted by jailing the pacemaker lead, and preserved lead function was observed postprocedurally.

In our setting, and considering that 85% of our patients were asymptomatic, cardiovascular magnetic resonance is routinely used for the early detection of venous baffle lesions. Patients with pacemakers (contraindicated for cardiovascular magnetic resonance) and suspected obstruction undergo diagnostic catheterization or computed tomography angiography.

Radiofrequency guidewires is a new technique in complete obstruction that has been used for the past 2 years without complications.4 Guidewire perforation requires optimal anatomical references to avoid complications. Biplane imaging is recommended, with simultaneous injection of contrast from the distal and proximal portions of the obstruction. In some patients with bilateral femoral obstruction, transhepatic access is chosen, because it allows retrograde angiographic access to the obstruction.

The high prevalence of intravenous pacemakers and the frequent need for lectrophysiological studies require adequate patency of vascular accesses. The presence of pacemaker leads in superior venous baffles accelerates stenosis. Therefore, stent implantation in the superior vena cava should be considered before pacemaker insertion.

The percutaneous treatment of follow-up lesions after Mustard operations is feasible and safe. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance is the diagnostic technique of choice for asymptomatic patients. Radiofrequency perforation may be a safe and effective option in patients with complete obstruction. The transhepatic approach is feasible and necessary in some patients to ensure a successful outcome.

We are grateful to everyone who has worked in medical-surgical pediatric cardiology at Hospital Ramón y Cajal for the benefit of these patients over the last 40 years, with special thanks to Dr. Bermúdez Cañete and Dr. Herráiz, who pioneered these procedures at our hospital.