In recent years, Catalonia has experienced a considerable increase in immigration from South Asia.1 This trend has been associated with a rise in hospital admissions for acute myocardial infarction (AMI) in South Asian patients, whose demographic characteristics, risk profile, and the extent of coronary disease seem to differ from that of individuals of European origin.

The aim of our study was to analyze the differences between South Asian and white Spanish patients admitted for a first AMI in a Catalonian reference hospital. This is a retrospective study including all South Asian patients (n=76) and white Spanish patients (n=1253) consecutively hospitalized for a first AMI in our coronary unit between 2002 and 2011. The demographic characteristics of the 2 groups were compared. South Asian and Spanish patient pairs were then matched for age (±2 years), sex, and year of presentation (±2 years), and comparisons were performed for coronary risk factors, clinical presentation, coronary anatomy, and in-hospital clinical course. Because of difficulties in matching South Asians and Spanish patients by age, the ratio ultimately defined was 1:1.6 (76 South Asian patients:127 Spanish patients). Data on the variables studied were obtained from the hospital admission records. Comparisons between the two groups were performed with the chi-square test for categorical variables and the Student t test or Mann Whitney U test for continuous variables, depending on whether or not they followed a normal distribution.

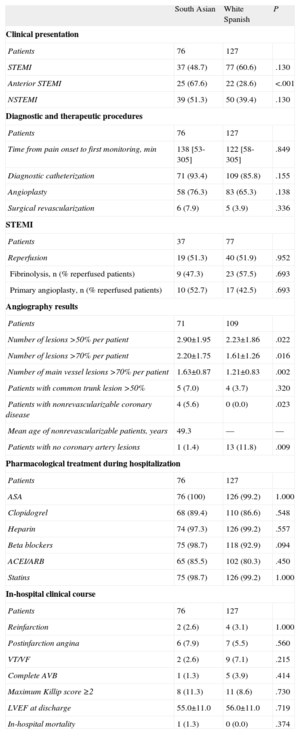

The majority of patients in the South Asian group were from Pakistan (78.9%), followed by India and Bangladesh (10.5%, respectively). As compared to the white Spanish population, South Asians were younger (47.5±8.7 vs 65.1±12.7 years; P<.001) and there was a higher percentage of men (92.1% vs 72.1%; P<.001). The prevalence of risk factors, comorbidities, and previous treatments in the two groups is shown in Table 1. The clinical presentation, results of angiography study, treatments, and in-hospital clinical course are summarized in Table 2.

Differences in Coronary Risk Factors, Biochemical Parameters, Associated Comorbidity, and Pharmacological Treatment Before Hospitalization Between Age- and Sex-Matched South Asian and White Spanish Patients.

| South Asian (n=76) | White Spanish (n=127) | P | |

| Age and sex after matching | |||

| Age, years | 47.5±8.7 | 48.6±8.1 | .400 |

| Men | 70 (92.1) | 117 (92.1) | .792 |

| Coronary risk factors | |||

| Diabetes mellitus | 22 (28.9) | 25 (19.7) | .180 |

| Hypertension | 21 (27.6) | 54 (42.5) | .048 |

| Active smoker/ex-smoker | 49 (64.5) | 106 (83.5) | .002 |

| Smokers, cigarettes/day | 20.8±9.8 | 26.6±11.0 | .011 |

| Cocaine use | 1 (1.3) | 12 (9.4) | .034 |

| Biochemical parameters | |||

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 181±46.9 | 196±46.3 | .032 |

| HDL-C, mg/dL | 35.5±8.9 | 42.3±10.8 | <.001 |

| LDL-C, mg/dL | 115±34.2 | 124±38.3 | .097 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL | 171 [129-234] | 158 [124-233] | .454 |

| HbA1c, % | 5.6 [5.0-8.3] | 5.2 [4.8-5.8] | .003 |

| Other comorbidities | |||

| Peripheral vasculopathy | 1 (1.3) | 5 (3.9) | .414 |

| Chronic renal failure | 0 (0.0) | 4 (3.1) | .299 |

| Thrombophilia | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.7) | 1.000 |

| HIV infection | 0 (0.0) | 4 (3.1) | .299 |

| Previous treatments | |||

| ASA | 3 (3.9) | 6 (4.7) | 1.000 |

| Clopidogrel | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.6) | .529 |

| Beta blockers | 3 (3.9) | 10 (7.9) | .378 |

| ACEI/ARB | 4 (5.3) | 23 (18.1) | .010 |

| Statins | 5 (6.5) | 31 (24.4) | .001 |

| Insulin/oral lipid lowering drugs | 15 (19.7) | 11 (8.7) | .039 |

ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; ASA, acetylsalicylic acid; HbA1c, glycohemoglobin; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol.

Data are expressed as n (%), mean± standard deviation, or median [interquartile range].

Differences in the Clinical Presentation of Acute Myocardial Infarction, Diagnostic and Therapeutic Procedures Performed, Angiography Results, Pharmacological Treatment During Hospitalization, and In-Hospital Clinical Course Between South Asian and White Spanish Patients Matched for Sex And Age.

| South Asian | White Spanish | P | |

| Clinical presentation | |||

| Patients | 76 | 127 | |

| STEMI | 37 (48.7) | 77 (60.6) | .130 |

| Anterior STEMI | 25 (67.6) | 22 (28.6) | <.001 |

| NSTEMI | 39 (51.3) | 50 (39.4) | .130 |

| Diagnostic and therapeutic procedures | |||

| Patients | 76 | 127 | |

| Time from pain onset to first monitoring, min | 138 [53-305] | 122 [58-305] | .849 |

| Diagnostic catheterization | 71 (93.4) | 109 (85.8) | .155 |

| Angioplasty | 58 (76.3) | 83 (65.3) | .138 |

| Surgical revascularization | 6 (7.9) | 5 (3.9) | .336 |

| STEMI | |||

| Patients | 37 | 77 | |

| Reperfusion | 19 (51.3) | 40 (51.9) | .952 |

| Fibrinolysis, n (% reperfused patients) | 9 (47.3) | 23 (57.5) | .693 |

| Primary angioplasty, n (% reperfused patients) | 10 (52.7) | 17 (42.5) | .693 |

| Angiography results | |||

| Patients | 71 | 109 | |

| Number of lesions >50% per patient | 2.90±1.95 | 2.23±1.86 | .022 |

| Number of lesions >70% per patient | 2.20±1.75 | 1.61±1.26 | .016 |

| Number of main vessel lesions >70% per patient | 1.63±0.87 | 1.21±0.83 | .002 |

| Patients with common trunk lesion >50% | 5 (7.0) | 4 (3.7) | .320 |

| Patients with nonrevascularizable coronary disease | 4 (5.6) | 0 (0.0) | .023 |

| Mean age of nonrevascularizable patients, years | 49.3 | — | — |

| Patients with no coronary artery lesions | 1 (1.4) | 13 (11.8) | .009 |

| Pharmacological treatment during hospitalization | |||

| Patients | 76 | 127 | |

| ASA | 76 (100) | 126 (99.2) | 1.000 |

| Clopidogrel | 68 (89.4) | 110 (86.6) | .548 |

| Heparin | 74 (97.3) | 126 (99.2) | .557 |

| Beta blockers | 75 (98.7) | 118 (92.9) | .094 |

| ACEI/ARB | 65 (85.5) | 102 (80.3) | .450 |

| Statins | 75 (98.7) | 126 (99.2) | 1.000 |

| In-hospital clinical course | |||

| Patients | 76 | 127 | |

| Reinfarction | 2 (2.6) | 4 (3.1) | 1.000 |

| Postinfarction angina | 6 (7.9) | 7 (5.5) | .560 |

| VT/VF | 2 (2.6) | 9 (7.1) | .215 |

| Complete AVB | 1 (1.3) | 5 (3.9) | .414 |

| Maximum Killip score ≥2 | 8 (11.3) | 11 (8.6) | .730 |

| LVEF at discharge | 55.0±11.0 | 56.0±11.0 | .719 |

| In-hospital mortality | 1 (1.3) | 0 (0.0) | .374 |

ACEI, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; ASA, acetylsalicylic acid; AVB, atrioventricular block; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; NSTEMI, non-ST-elevation acute myocardial infarction; STEMI, ST-elevation acute myocardial infarction; VF, ventricular fibrillation; VT, ventricular tachycardia.

Data are expressed as n (%), mean± standard deviation, or median [interquartile range].

The analysis of our series showed that South Asians admitted for a first AMI in our setting are a young, mainly male population, with glucose metabolism alterations, and low concentrations of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol. Although the demographic characteristics observed can be explained in part by the phenomenon of migration selection, the results in our series are in keeping with findings from multinational studies as well as those performed in other host countries (United States, Canada), where the South Asian ethnic group was seen to be the youngest population experiencing a first AMI.2

It has been proposed that this group may have accelerated atherosclerotic disease resulting from a strong genetic predisposition enhanced by high rates of consanguinity, with insulin resistance as the main pathophysiological mechanism.3 The genetic-metabolic hypothesis concurs with the observations in South Asians in our study. Coronary risk in these patients was notable for abnormalities in glucose metabolism (a larger percentage of patients had previous diabetes mellitus treatment and higher glycohemoglobin concentrations) and in lipid metabolism (lower high-density lipoprotein cholesterol values, which have a recognized anti-inflammatory and antithrombotic action).

Furthermore, South Asians in our series presented a significantly lower prevalence of hypertension, smoking, and cocaine abuse than the white Spanish population, with similar values of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, but a lower prevalence of previous treatments with statins. Studies performed in Britain have reported contradictory results regarding the presence of these risk factors in South Asian patients, and this has been related to the heterogeneity of the subgroups analyzed,4 which makes extrapolation to our setting difficult. For its part, the risk profile observed among the young Spaniards in our series is in keeping with previous findings,5 in which early infarction has been associated with high rates of smoking and hypercholesterolemia, and glucose metabolism disorders have a smaller role. Our study highlights the specific features of cardiovascular risk in South Asians in our setting and the differences with respect to the young Spanish population.

There were no significant differences between the 2 groups in the clinical presentation of AMI (with or without ST elevation). Nonetheless, among patients with ST elevation AMI, there was a significantly higher percentage of anterior AMI in South Asian patients. In addition, coronary angiography showed more severe disease in these patients, and a larger number were considered to have nonrevascularizable lesions. AMI without coronary lesions was more common in the white Spanish population. These observations indicate that coronary disease in South Asians is related more to accelerated atherosclerosis than to predominantly thrombotic or vasospastic processes.

Despite the differences described, the 2 groups presented a similar in-hospital clinical course with low complication rates and mortality, which was likely due to the young age of the patients, low prevalence of comorbidities, absence of significant differences in the treatment received, and the improved in-hospital prognosis of AMI observed in our setting.6

This series is the first in Spain to address ischemic heart disease in South Asian immigrant patients. Knowledge of the differential characteristics of this ethnic group can facilitate the development of primary and secondary prevention strategies adapted to their risk profile.

.