After an in-hospital cardiorespiratory arrest, fewer than 25% of patients survive until hospital discharge, and substantial neurological sequelae are present in around 30% of survivors.1 Patients’ preferences regarding cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) are tied to their perception of the chances of a successful outcome.2,3 An excessive optimism in our patients with regard to maneuvers such as CPR in the context of cardiovascular disease may have an impact on their expectations, thereby influencing whether they opt for do not resuscitate orders or advance directives.

Our main objective was to determine the prognosis of cardiology patients after cardiorespiratory arrest and to assess whether this may have an impact on their desire for resuscitation. To this end, we conducted a descriptive study based on a voluntary and anonymous survey (Figure), administered during a private face-to-face interview with a single cardiologist (J. Ruiz-García) in a consecutive series of patients after their visit to the cardiologist in a general hospital.

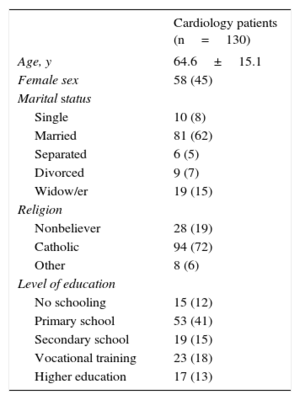

In total, 130 consecutive cardiology patients were included in the study (Table). No patient refused to participate and only 2 preferred not to answer a question about do not resuscitate orders.

Demographic Characteristics of Patients Included in the Study

| Cardiology patients (n=130) | |

|---|---|

| Age, y | 64.6±15.1 |

| Female sex | 58 (45) |

| Marital status | |

| Single | 10 (8) |

| Married | 81 (62) |

| Separated | 6 (5) |

| Divorced | 9 (7) |

| Widow/er | 19 (15) |

| Religion | |

| Nonbeliever | 28 (19) |

| Catholic | 94 (72) |

| Other | 8 (6) |

| Level of education | |

| No schooling | 15 (12) |

| Primary school | 53 (41) |

| Secondary school | 19 (15) |

| Vocational training | 23 (18) |

| Higher education | 17 (13) |

Data are expressed as n (%) or mean±standard deviation.

The predicted mean survival at hospital discharge (question 1A) according to the responses of our group of patients was 75.6%±23.0% (median 80%, interquartile range 60%-94%). The predicted mean survival free of substantial neurological deterioration (question 1B) was 64.5%±26.2% (median 70%, interquartile range 50%-86%).

With these expectations, 116 patients (89%) wished to be resuscitated in their current state, 1 would refuse CPR, and 12 (9%) had never considered this question. In the event of a change in their clinical condition and diagnosis with a chronic disease with a life expectancy less than 12 months, this number was significantly reduced (71 patients, 55%; P<.01) while the number of patients who would refuse CPR or who had never considered this question increased to 22 (17%; P<.01) and 34 (26%; P<.01), respectively.

Twenty-eight patients (22%) reported never having seen or been present at a CPR; of those who had, most (86%) had seen it in a film or television series.

Only 1 patient had deposited an advanced directives document or living will. However, 89 (69%) wanted to be the ones who took the decision about end-of-life care, compared with 28 (22%) and 12 (9%) who wanted the physician or a family member, respectively, to take that decision.

The cardiology patients interviewed have a highly optimistic outlook of the outcomes of CPR in the context of in-hospital cardiorespiratory arrest. It is highly likely that these expectations so far removed from reality have influenced the desire of the majority to be resuscitated in their current clinical conditions, and even in the case of a disease that would significantly shorten their life expectancy.

The professionals who treat cardiology patients should be conscious of this situation and encourage decision-making based on desired, objective, real, and current information. If we do not provide appropriate information, patients may make their decisions based on false expectations and a much more hopeful outlook than is actually the case, thereby detracting from their right to provide an informed consent. Of particular note is that the optimism shown by our cardiology patients, which although common to most patients, exceeds that observed in another analyses. For example, in the study by Jones et al,4 the overall survival rate was cited as 65%. More recently, the mean survival at discharge after cardiorespiratory arrest in a healthier and younger population than ours was 54%,5 still rather distant from reality but closer to the 76% survival predicted by our cardiology patients.

Overestimation of the chances of survival and recovery after CPR is relevant, as it may lead many patients to decide to refuse, for example, a do not resuscitate order in situations in which the chances of survival are low or the risk of neurological complications is high, thereby often hindering fluid dialogue between cardiologist and patient about the end of life. It is known that when patients are actually aware of the chances of successful CPR, many change their wish and give a do not resuscitate order. In fact, when a group of patients was questioned about their wishes after a cardiorespiratory arrest, 41% opted for resuscitation before knowing the probability of survival on discharge after CPR, whereas after being made aware of the prognosis, the percentage of patients who still wished to be resuscitated decreased to 22%.2

Our findings show that, for the first time, the predicted survival after in-hospital CPR in Spanish cardiology patients differs significantly from reality. With these expectations, a large majority would wish in their current medical condition to be resuscitated in the event of cardiorespiratory arrest. Many of these would not change their wishes even if they had a disease that clearly limited their life expectancy.