A 53-year-old Caucasian woman was admitted to hospital for increasing dyspnea on exertion and episodes of near fainting. Echocardiography revealed pericardial effusion with evidence of tamponade. The chylous nature of the fluid was confirmed by the high level of triglycerides and by a cholesterol–triglyceride ratio, which was characteristically less than 1. Cytology demonstrated an abundance of lymphocytes. Surgical pericardial window was performed. Repeat echocardiography revealed recurrent severe effusion, for which a pericardial catheter was kept in place to enable continuous drainage. When the patient was placed on a low fat diet enriched with medium-chain triglycerides, drainage was reduced but was persistent.

The patient underwent extensive evaluation to identify the cause of the chylous pericardium. Routine laboratory tests demonstrated normal blood counts, electrolytes, liver function, lipid profile, serum urea, serum creatinine, serum calcium, and lactate dehydrogenase. There was no sign of systemic inflammatory reaction. Computed tomography (CT) of the chest revealed no obstruction to the thoracic duct. Pericardial fluid cultures were repeatedly negative for a bacterial cause. Tuberculosis was excluded by a negative Mantoux test and by repeat cultures and microscopic examination of specimens from the pericardial effusion.

Unfortunately, severe bilateral pleural effusion developed after withdrawal of the pericardial catheter. After multidisciplinary team discussion, the patient underwent surgical ligation of the thoracic duct. After initial improvement, the patient had persistent bilateral pulmonary effusion and moderate pericardial effusion. Thus, we used a percutaneous approach aiming to reduce the chylopericardial communication by selective embolization.

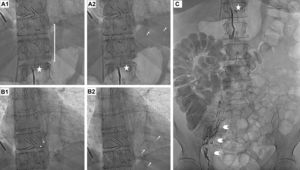

Lymphography was attempted through the right inguinal lymph node, injecting 4 cc of Lipiodol (ethiodized oil, Guerbert USA, Bloomington, IN, USA). We observed peri-iliac and pericaval retroperitoneal lymph node repletion, filling the cisterna chyli and the efferent ducts developing the origin of the thoracic duct, properly ligated by surgical clips. We confirmed a mild contrast extravasation into the pericardium (Figure 1 and Videos 1 and 2 of the supplementary data), demonstrating a leak from the retrocrural lymph nodes. We were able to selectively record the stained microparticles moving through the pericardium, providing in vivo confirmation of the connection, and explaining the continuous recurrent pericardial effusion despite surgical ligation of the thoracic duct.

Lymphography showing ligation of the thoracic duct by surgical clips (A-B-C, stars). A2-B2 show spontaneous extravasation from the iodinated drops from the lymphatic system into the pericardium (arrows) by periiliac and pericava retroperitoneal injection of lymphatic contrast (ethiodized oil; C: arrowheads).

The first embolization procedure was performed after lymphography through the right inguinal lymph node with 4 cc lipiodol (ethiodized oil). We observed repletion of the peri-iliac, pericaval and cisterna chyli lymphatic system, confirming the stoppage at the surgical clips (thoracic duct). We identified a mild leakeage through the retrocrural lymph nodes. Using CT-guided direct puncture, the cisterna chyli was embolized with 2 cc of acrylate comonomer glubran (biodegradable synthetic surgical glue). A repeat procedure was performed 1 month later, through the same access. The cisterna chyli was still patent and thus we confirmed an incomplete previous embolization. We performed a second CT-guided direct puncture of the cisterna, injecting 0.5 cc of glubran.

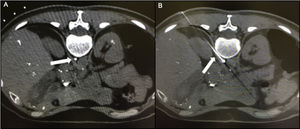

Chylopericardium can be a consequence of thoracic and cardiac surgery, chest trauma, mediastinal tumors, radiotherapy, tuberculosis, and subclavian vein thrombosis.1–6 Primary idiopathic chylopericardium was first described by Groves and Effler in 1954.1 It is a rare clinical entity characterized by the accumulation of chyle within the pericardial cavity without a definitive cause.1–6 Most cases occur in children or young adults, nearly 40% are asymptomatic, and tamponade is uncommon (5%-8%). Although the exact pathophysiology of primary chylopericardium has not been established, reflux of chylous fluid into the pericardial space has been suggested as the etiology.3–5 The cisterna chyli is not easily identified on CT or magnetic resonance images due to its small size and lack of specific position and can be misidentified with lymphatic or venous structures (Figure 2). Damage to the thoracic duct valves and the communication of the thoracic duct to the pericardial lymphatic system or abnormally elevated pressure in the thoracic duct could cause chylous fluid reflux. As described in this patient, conservative treatment of primary chylopericardium is rarely successful. Thus, surgical ligation and excision of the thoracic duct just above the diaphragm is required,4–6 combined with partial pericardiectomy.4–6 However, several patients have recurrent chylopericardium. Nearly 40% of patients have 2 or multiple channels instead of a single thoracic duct.5,6 Moreover, it is sometimes the result of multiple lymphatic connections from retrocrural lymph nodes rather than a single efferent channel from the cisterna chyli,5 as in our patient. This might explain why ligation of the thoracic duct was ineffective.

A: CT scan showing the cisterna chyli. B: Needle puncturing the cisterna chyli. Videos 1 and 2 of the Supplementary data show in vivo lymphographic recording of spontaneous leakage of lymphatic system particles into the pericardium after injection of ethiodized oil contrast into the right inguinal lymph node, demonstrating a connection between both the lymphatic system and the pericardium.

In our case, this might be the result of elevated pressure in the thoracic duct below the surgical ligation and subsequent increased flow through the connections toward the pericardium (and pleura). Percutaneous approaches have been proposed,3–6 as performed in our patient. Since percutaneous treatment does not preclude surgical treatment if it fails, it is reasonable to propose a percutaneous approach as the initial treatment for thoracic duct lesions. This combined approach, percutaneous and surgical, might be necessary in many patients with recurrent chylopericardium or chylothorax. Surgical glue was used to embolize the cisterna chyli as it has been shown to be effective for embolization of small structures. Alternative embolization options could have been the application of microcoils or microspheres.6 They are released through a microcatheter placed in the thoracic duct, sealing while withdrawing the microcatheter from the cranial position toward the cisterna chyli.6 We provide valuable evidence of connections between the chylous system and the pericardium, demonstrated by in vivo fluoroscopy recording in the case of a 53-year-old woman with primary idiopathic chylopericardium presenting as cardiac tamponade.

In conclusion, percutaneous embolization of these connections can be helpful in this complex disease.