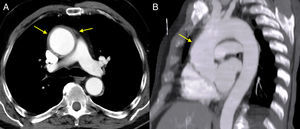

A 71-year-old man with controlled hypertension and no family history of interest presented with a 3-h history of severe central chest pain radiating to his back. He reported having a headache and joint pains, particularly in his shoulders, for the last few days. Two years previously, he had undergone an echocardiogram, exercise testing, and cardiac catheterization for chest pain, with no significant findings. The physical examination was unremarkable. In view of the nature of the pain, we performed computed tomography angiography, which showed an ascending aortic aneurysm with thickening of the aortic wall (Fig. 1). The results of laboratory tests, including D-dimer, were normal, except for an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (91 mm/h) and C-reactive protein (1.8 mg/L). We decided to confirm the suspected diagnosis and rule out intramural hematoma by means of magnetic resonance angiography, which showed a thoracic ascending aortic aneurysm with a maximum diameter of 47mm and wall thickening of 7 mm, without aortic root or arch involvement (Figs. 2A and B). We also performed a single-photon emission computed tomography scan with 99mTc. Delayed imaging showed persistent activity in the thoracic aorta, indicating inflammation.

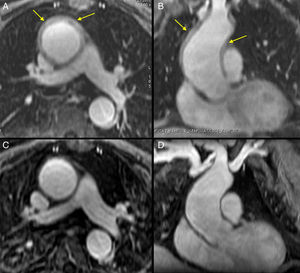

Magnetic resonance image with contrast-enhanced T1-weighted FAME sequences. A (axial image) and B (coronal image): Note the ascending aortic aneurysm, with a maximum diameter of 47 mm before the brachiocephalic trunk and 7-mm thickening of the ascending and descending aortic walls. C and D: Magnetic resonance follow-up 7 months after treatment, with the same slices; note the normal aortic wall thickness and persisting aortic aneurysm.

Aortitis was diagnosed from the clinical, laboratory and imaging findings. Based on the patient's age (> 50 years), clinical features (new-onset headache and symptoms of polymyalgia rheumatica), the elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein, and the aforementioned findings of imaging studies, giant cell arteritis (GCA) was diagnosed. A temporal artery biopsy showed no vasculitis, and corticosteroid therapy was started. When investigating the etiology, we ruled out infectious causes.

During follow-up, the symptoms resolved completely, with a gradual decrease in erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein and return to normal values, and therefore the corticosteroids were reduced. A follow-up magnetic resonance imaging scan was performed after 6 months and showed no thickening of the aortic wall or increased aneurysm size (Figs. 2C and D).

The term aortitis describes inflammation of the aortic wall. The leading causes are of rheumatic origin, in which GCA accounts for over 75% of cases, followed by Takayasu arteritis. Infectious and idiopathic etiologies are much less common.1

Giant cell arteritis is a vasculitis that affects large and medium vessels2,3 with an incidence of 15-30/100 000 population aged more than 50 years.1,4 Vascular inflammation may be focal or widespread, which explains the high rate of false negative results in temporal artery biopsy.3,4 The aortic wall is affected in 15% to 22% of cases, and the risk of aortic aneurysm is 17 times higher than in healthy individuals.1,4,5 The pathogenesis is unknown but is believed to originate in antigen-driven cell-mediated autoimmune processes associated with specific human leukocyte antigens (HLA-DR4). Histopathology shows evidence of an inflammatory infiltrate of the media, adventitia and vasa vasorum, with a predominance of lymphocytes, macrophages, and multinucleated giant cells.1,4

The clinical presentation of aortitis varies across a wide spectrum of signs and symptoms. Classic manifestations are headache, back pain, polymyalgia rheumatica, and fever.5 Aortitis can also present as severe aortic insufficiency or aortic aneurysm. Acute aortic syndrome is a less common manifestation, but it should be noted that patients with GCA are at a higher risk of aortic dissection.6

An initial evaluation of suspected aortitis should include determination of erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, and specific antibodies, blood cultures, tuberculosis testing, and serology for syphilis and other infectious diseases.3

The diagnostic criteria for GCA are: age greater than or equal to 50 years, headache, temporal artery abnormality, erythrocyte sedimentation rate greater than or equal to 50 mm/h and arterial biopsy showing vasculitis. The presence of 3 of these criteria has a sensitivity of 94% and a specificity of 91%.1,3

Diagnostic imaging is essential in aortitis. Computed tomography angiography is the first-line diagnostic approach because it is widely available and can rule out other causes of chest pain. This procedure can reveal changes in the lumen and wall thickening, but other diseases, such as aortic dissection, intramural hematoma and penetrating atherosclerotic ulcer, may mimic acute aortitis, and consequently computed tomography angiography has a lower diagnostic value for GCA.2

Magnetic resonance angiography is more effective and, because it can demonstrate inflammatory activity and vessel wall edema and can also characterize structural changes, is the technique of choice for diagnosis and monitoring.2,3

Nuclear imaging also shows inflammatory activity but is less precise in identifying anatomical location.

Giant cell arteritis is treated with prednisone, with the aim of achieving complete remission.1,4 The relapse rate can be as high as 50%. In these patients and in those who are refractory to treatment, the use of other drugs such as methotrexate, azathioprine, and infliximab has been studied.1,5

Patients with aortitis should be reviewed regularly, with close monitoring of symptoms, vascular signs, inflammatory markers, and imaging studies to monitor treatment response and check for any increase in aortic diameter. The indications for surgical correction are the same as for other aneurysms.

The incidence of aortitis secondary to GCA may be underestimated because it is not systematically considered in all patients with aortic aneurysm and vasculitis. This can have serious consequences, especially considering that GCA is potentially curable or, at the very least, controllable.