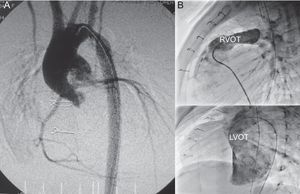

Aortic valve atresia, or severe hypoplasia associated with ventricular septal defect and normal-sized ventricles, is an exceptional entity in neonates. Biventricular correction is feasible in a single intervention (described by Yasui in 1987)1 or in 2 stages, using a Norwood procedure followed by a Rastelli operation in order to subsequently establish biventricular physiology (successfully used in 1981).2 This approach involves reconstructing the ascending aorta by using the Damus-Kaye-Stansel technique (Figure A) and closing the septal defect and the conduit between the right ventricle and the pulmonary artery (Figure B), sometimes combined with reconstruction of the aortic arch. We present the results of the medium-term follow-up in our series.

A: Angiography; ascending aorta reconstructed with the pulmonary trunk (Damus-Kaye-Stansel). B: Right catheterization, outflow tract of the right ventricle with contrast flow through the right ventricle-pulmonary artery duct; left catheterization, outflow tract of the left ventricle with contrast flow toward the neoaorta. RVOT, right ventricle outflow tract; LVOT, left ventricle outflow tract.

Between 1990 and 2013, 27 patients (mean age, 19 [2-112] days; mean weight, 3.25 [2.1-5.2] kg) with this diagnosis (aortic valve atresia in 18 and severe hypoplasia in 9, defined as ring diameter < 3mm) underwent biventricular repair (interrupted aortic arch in 14 and aortic coarctation in 7). Primary repair (Yasui surgery)1 was performed in 19 patients (70.4%), and the 2 -stage approach in 8 (29.6%), using the Norwood2 technique followed by a Rastelli operation at 9.6 (0.3-29.2) months.

The inclusion criteria (based on 2-dimensional echocardiography) for choosing this repair technique were lack of fibroelastosis in the left ventricle, good ventricular function, mitral ring z-score > -2, left ventricle quotient (long axis) > 0.8, left ventricle ≥ 20mL/m2 and nonrestrictive ventricular septal defect. The staged approach was implemented as standard in 2008.

Data were extracted from our database (HeartSuite, Systeria, Inc, Glasgow, United Kingdom) and from medical records. The analysis was performed using R software v3.0.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). The Kaplan-Meier (log-rank test) was used for the survival analysis. A P-value of < .05 was considered statistically significant.

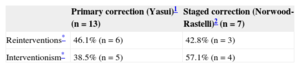

Overall 30-day mortality was 25.9% (n = 7), and operative mortality was 7.4% (n = 2, both following Yasui1 surgery with failure of extracorporeal circulation during the interval before the implantation of a longer-term circulatory support technique). The remaining causes of early death were of non-cardiac origin. There were no deaths between the stages of the 2-stage approach. Mortality during follow-up (mean [standard deviation], 8.4 [5.3] [0.9 to 23] years) was 10.5% (n = 2, both following primary correction: sudden death of undetermined origin, episodes of ventricular tachycardia, and irreversible cardiac arrest). Of the 20 survivors, 9 (45%) required intervention (arch stenosis or recoarctation in 5, and conduit stenosis in 9), and 9 underwent surgery again for conduit replacement (pacemaker implantation in 1 patient after obstructive resection of the left outflow tract). Of the initial survivors (n = 20) 95%, 85%, 50% and 35% had not required reintervention after 1, 2, 5, and 10 years, and 70%, 65%, and 55% were without percutaneous procedures after 1, 2, and 5 years. The incidence of reinterventions and interventionism in each group according to the surgical technique used is shown in the Table. Overall survival during follow-up (n = 20) was 95% at 10 years.

Primary correction and 2-stage surgery are 2 options with very similar results for biventricular correction in this context,3,4 representing a safe and effective strategy with excellent medium-term survival, although with a high rate of reintervention/interventionism.

Yasui surgery1 (a high-risk procedure for neonates, who are occasionally underweight), avoids provisional univentricular physiology and allows complete correction. The Norwood technique2 avoids the initial complexity of corrective surgery, involves 2 normal ventricles contributing to cardiac output, and allows a period of growth prior to final biventricular correction. This may facilitate better selection of candidates, as there may be some patients who will benefit from a univentricular physiology and who could not otherwise have been identified, which is especially important in the case of impaired left ventricular function.

A study by the Congenital Heart Surgeons’ Society Data Center (Toronto) showed that primary biventricular repair in neonates in cases of critical aortic stenosis led to a high reintervention rate (50% at 3 years). This resulted in a 30-day mortality of 60%, which could reflect an inadequate initial indication,5,6 possibly due to a belief that early septation must be achieved. However, the rationale for choosing one or other surgical option remains controversial and will continue to be debated.