Encouraging results at long-term follow-up have been reported from non-randomized registries and randomized trials following percutaneous coronary intervention with drug-eluting stent implantation for unprotected left main stenosis. However, information on very long-term (>5-year) outcomes is limited. The aim of this study was to assess the very long-term outcomes (6-years) following drug-eluting stent implantation for left main disease.

MethodsAll consecutive patients with unprotected left main stenosis electively treated with drug-eluting stent implantation, between March 2002 and May 2005, were analyzed according to the location of the left main lesion (distal bifurcation vs ostial/body).

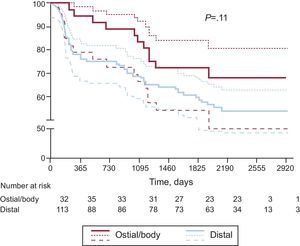

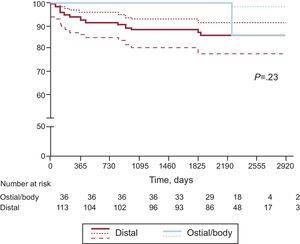

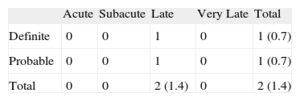

ResultsThe study included 149 patients: 113 with distal bifurcation and 36 with ostial/body lesion. Triple-vessel disease was significantly higher in the distal than in the ostial/body group (52.2% vs 33.2%, P=.05). At 6-years of follow-up, the cumulative major adverse cardiovascular event rate was 41.6% (45.1% distal vs 30.6% ostial/body, P=0.1), including 18.8% any death (22.1% distal vs 8.3% ostial/body, P=.08), 3.4% myocardial infarction (3.5% distal vs 2.8% ostial/body, P=1), and 15.4% target lesion revascularization (18.6% distal vs 5.6% ostial/body, P=.06). The composite of cardiac death and myocardial infarction was 10.7% (13.3% distal vs 2.8% ostial/body, P=.1) while the definite/probable stent thrombosis rate was 1.4% (all in the distal group).

ConclusionsAt 6-year clinical follow-up, percutaneous coronary intervention with drug-eluting stent implantation for unprotected left main disease was associated with acceptable rates of cardiac death, myocardial infarction and stent thrombosis. Favorable long-term outcomes in ostial/body lesions compared to distal bifurcation lesions were confirmed at long-term clinical follow-up.

Keywords

.

IntroductionCoronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) is the standard of care for patients with critical unprotected left main coronary artery (ULMCA) stenosis1 since it was found to improve late survival vs medical therapy.2 Recent advances in technology (such as drug-eluting stent [DES] introduction and intravascular ultrasound [IVUS] use), operator experience, and antiplatelet therapy have led to a wide expansion of the role of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) in selected patients with ULMCA lesions and low-to-moderate SYNTAX (Synergy Between Percutaneous Coronary Intervention With TAXUS and Cardiac Surgery) scores.3 According to current guidelines, the treatment of ULMCA disease with PCI has a class IIb indication.1 Registry data on PCI with DES implantation in ULMCA lesions have demonstrated that this approach is safe and effective at medium-term clinical follow-up.4–8 Although recent reports showed favorable outcomes at medium- and long-term clinical follow-up,9,10 few studies have evaluated the very long term clinical outcomes (>5 years) of this treatment strategy.11,12 The aim of the present study was to report the 6-year clinical outcomes following treatment of ULMCA stenoses with PCI and DES implantation.

MethodsA retrospective cohort analysis was performed of all consecutive patients with ULMCA stenosis treated with either a sirolimus-eluting (SES) (Cypher, Cordis, Johnson and Johnson, Miami Lake, Florida, United States) or paclitaxel-eluting stent (PES) (Boston Scientific, Natick, Massachussets, United States) between March 2002 and May 2005 in a tertiary referral center. The decision to perform PCI rather than CABG was taken in the presence of suitable anatomy and lesion characteristics for stenting, in patients without contraindications to at least 6 months of dual antiplatelet therapy, and 1 of the following conditions: a) high surgical risk defined as EuroSCORE (European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation)≥6; b) patient refusal to undergo CABG, and c) referring physician preference. All patients were carefully informed about the alternative treatment options and PCI-related risks before being asked to give written informed consent to undergo the procedure.

Intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP) and IVUS-guidance left main PCI were decided at the operator's discretion.

In particular, preprocedural factors that were considered to merit prophylactic use of IABP for elective ULMCA PCI included: a) systolic blood pressure≤100mmHg; b) severe left ventricular dysfunction (i.e. ejection fraction [EF]≤35%); c) recent presentation for decompensated heart failure; d) dominant left circumflex or occluded dominant right coronary artery, and e) performance of atherectomy. Clinical follow-up was performed by telephone contact or an office visit at 1, 6, and 12 months and annually after the first year. Patients were analyzed according to the location of the ULMCA lesion: ostial/body vs distal bifurcation.

Angiographic follow-up was scheduled between 4 and 9 months or earlier if non-invasive evaluation or clinical presentation suggested the presence of ischemia. All adverse events were verified by reviewing the medical records of the patients followed at our institution or by contacting the patients’ physicians and reviewing the hospital records of patients followed elsewhere.

All patients were pre-treated with acetylsalicylic acid (100mg/day) and a thienopyridine (ticlopidine 250mg twice daily or clopidogrel 75mg/day) was started at least 5 days before the procedure. At discharge all patients were prescribed life-long acetylsalicylic acid and a thienopyridine for at least 6-12 months irrespective of PES or SES implantation. Dual antiplatelet therapy was prolonged indefinitely in case of ULMCA plus multivessel DES implantation. Detailed information on adherence as well as the reasons for and date of dual antiplatelet therapy discontinuation was obtained in all patients.

DefinitionsThe following major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) were analyzed cumulatively at the 6-year clinical follow-up: any death, myocardial infarction (MI) and any revascularization. Deaths were classified as either cardiac or non-cardiac. Clinical end-points (death, cardiac death, target lesion revascularization [TLR], target vessel revascularization, peri-procedural MI and stent thrombosis [ST]) were defined on the basis of the Academic Research Consortium definitions.13

The EuroSCORE, which is based on patient-, cardiac- and operation-related factors, was used to stratify the risk of death at 30 days. According to the scoring system, patients were stratified as high risk in the presence of a EuroSCORE≥6. The SYNTAX score was also calculated from pre-intervention angiograms to reflect an anatomical assessment with higher scores indicating more complex coronary disease.14 A low score was defined as≤22, an intermediate score from 22-32, and a high score≥33, as described in the SYNTAX trial.14

Statistical AnalysisContinuous variables are presented as mean (standard deviation) or median [interquartile range]. Categorical variables are presented as raw numbers with percentages. The normality of the distribution of all the continuous variables was assessed by the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Continuous variables were compared by the independent sample t-test or Mann-Whitney U-test. Categorical variables were compared by the Chi-square statistic or Fisher's exact test. Time-to-event data were analyzed with the Kaplan-Meier method and groups were compared with the log rank test. Multivariable Cox proportional-hazards regression modeling was performed to determine the independent predictors of MACE, using purposeful selection of covariates. Variables associated at univariate analysis with MACE (all with a P-value<.1) and those judged to be of clinical importance from previously published literature were eligible for inclusion into the multivariable model-building process. Candidate variables included age, sex, stent type, diabetes, hypertension, EF, distal ULMCA lesion, peripheral artery disease, significant cardiac valve disease, glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors, number of stents per lesion, stent diameter, stent length, final maximum atmosphere of stent implantation, use of rotablator, SYNTAX score, and EuroSCORE. The goodness-of-fit of the Cox multivariable model was assessed with the Grønnesby-Borgan-May test.15,16 The results of the Cox proportional-hazards analyses are reported as adjusted hazard ratios with associated 95% confidence intervals and P-value. A P-value of<.05 was considered to be statistically significant and all reported P-values are 2 sided. The statistical analysis was performed using STATA 9.0 (Stata Corporation, College Station, Texas, United States).

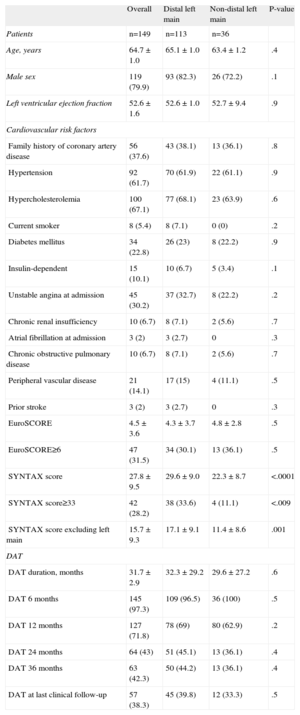

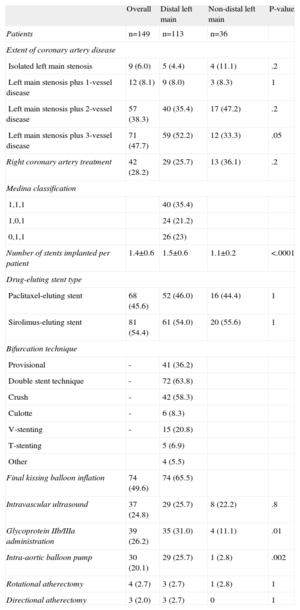

ResultsBaseline clinical, lesion and procedural characteristics are summarized in Tables 1 and 2. The comparison of the 113 patients with distal bifurcation and 36 patients with ostial/body lesions showed no significant differences in baseline clinical characteristics, except for the presence of triple-vessel disease (52.2% vs 33.2%; P=.05), SYNTAX score (29.6 [9.0] vs 22.3 [8.7]; P<.001), the use of an IABP (25.7% vs 2.8%; P<.001), the administration of glycoprotein IIb-IIIa inhibitors (31.0% vs 11.1%; P=.01), and the number of stents implanted for the treatment of the ULMCA lesion (1.5 [0.6] vs 1.1 [0.2]; P<.0001) which were higher in the distal group (Table 2).

Patients’ Clinical Characteristics

| Overall | Distal left main | Non-distal left main | P-value | |

| Patients | n=149 | n=113 | n=36 | |

| Age, years | 64.7 ± 1.0 | 65.1 ± 1.0 | 63.4 ± 1.2 | .4 |

| Male sex | 119 (79.9) | 93 (82.3) | 26 (72.2) | .1 |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction | 52.6 ± 1.6 | 52.6 ± 1.0 | 52.7 ± 9.4 | .9 |

| Cardiovascular risk factors | ||||

| Family history of coronary artery disease | 56 (37.6) | 43 (38.1) | 13 (36.1) | .8 |

| Hypertension | 92 (61.7) | 70 (61.9) | 22 (61.1) | .9 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 100 (67.1) | 77 (68.1) | 23 (63.9) | .6 |

| Current smoker | 8 (5.4) | 8 (7.1) | 0 (0) | .2 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 34 (22.8) | 26 (23) | 8 (22.2) | .9 |

| Insulin-dependent | 15 (10.1) | 10 (6.7) | 5 (3.4) | .1 |

| Unstable angina at admission | 45 (30.2) | 37 (32.7) | 8 (22.2) | .2 |

| Chronic renal insufficiency | 10 (6.7) | 8 (7.1) | 2 (5.6) | .7 |

| Atrial fibrillation at admission | 3 (2) | 3 (2.7) | 0 | .3 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 10 (6.7) | 8 (7.1) | 2 (5.6) | .7 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 21 (14.1) | 17 (15) | 4 (11.1) | .5 |

| Prior stroke | 3 (2) | 3 (2.7) | 0 | .3 |

| EuroSCORE | 4.5 ± 3.6 | 4.3 ± 3.7 | 4.8 ± 2.8 | .5 |

| EuroSCORE≥6 | 47 (31.5) | 34 (30.1) | 13 (36.1) | .5 |

| SYNTAX score | 27.8 ± 9.5 | 29.6 ± 9.0 | 22.3 ± 8.7 | <.0001 |

| SYNTAX score≥33 | 42 (28.2) | 38 (33.6) | 4 (11.1) | <.009 |

| SYNTAX score excluding left main | 15.7 ± 9.3 | 17.1 ± 9.1 | 11.4 ± 8.6 | .001 |

| DAT | ||||

| DAT duration, months | 31.7 ± 2.9 | 32.3 ± 29.2 | 29.6 ± 27.2 | .6 |

| DAT 6 months | 145 (97.3) | 109 (96.5) | 36 (100) | .5 |

| DAT 12 months | 127 (71.8) | 78 (69) | 80 (62.9) | .2 |

| DAT 24 months | 64 (43) | 51 (45.1) | 13 (36.1) | .4 |

| DAT 36 months | 63 (42.3) | 50 (44.2) | 13 (36.1) | .4 |

| DAT at last clinical follow-up | 57 (38.3) | 45 (39.8) | 12 (33.3) | .5 |

DAT, dual antiplatelet therapy; EuroSCORE, European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation; SYNTAX, Synergy Between Percutaneous Coronary Intervention With TAXUS and Cardiac Surgery.

Chronic renal insufficiency was defined as serum creatinine≥2.0mg/dL.

Data are expressed as mean±standard deviation or no. (%).

Lesion and Procedural Characteristics

| Overall | Distal left main | Non-distal left main | P-value | |

| Patients | n=149 | n=113 | n=36 | |

| Extent of coronary artery disease | ||||

| Isolated left main stenosis | 9 (6.0) | 5 (4.4) | 4 (11.1) | .2 |

| Left main stenosis plus 1-vessel disease | 12 (8.1) | 9 (8.0) | 3 (8.3) | 1 |

| Left main stenosis plus 2-vessel disease | 57 (38.3) | 40 (35.4) | 17 (47.2) | .2 |

| Left main stenosis plus 3-vessel disease | 71 (47.7) | 59 (52.2) | 12 (33.3) | .05 |

| Right coronary artery treatment | 42 (28.2) | 29 (25.7) | 13 (36.1) | .2 |

| Medina classification | ||||

| 1,1,1 | 40 (35.4) | |||

| 1,0,1 | 24 (21.2) | |||

| 0,1,1 | 26 (23) | |||

| Number of stents implanted per patient | 1.4±0.6 | 1.5±0.6 | 1.1±0.2 | <.0001 |

| Drug-eluting stent type | ||||

| Paclitaxel-eluting stent | 68 (45.6) | 52 (46.0) | 16 (44.4) | 1 |

| Sirolimus-eluting stent | 81 (54.4) | 61 (54.0) | 20 (55.6) | 1 |

| Bifurcation technique | ||||

| Provisional | - | 41 (36.2) | ||

| Double stent technique | - | 72 (63.8) | ||

| Crush | - | 42 (58.3) | ||

| Culotte | - | 6 (8.3) | ||

| V-stenting | - | 15 (20.8) | ||

| T-stenting | 5 (6.9) | |||

| Other | 4 (5.5) | |||

| Final kissing balloon inflation | 74 (49.6) | 74 (65.5) | ||

| Intravascular ultrasound | 37 (24.8) | 29 (25.7) | 8 (22.2) | .8 |

| Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa administration | 39 (26.2) | 35 (31.0) | 4 (11.1) | .01 |

| Intra-aortic balloon pump | 30 (20.1) | 29 (25.7) | 1 (2.8) | .002 |

| Rotational atherectomy | 4 (2.7) | 3 (2.7) | 1 (2.8) | 1 |

| Directional atherectomy | 3 (2.0) | 3 (2.7) | 0 | 1 |

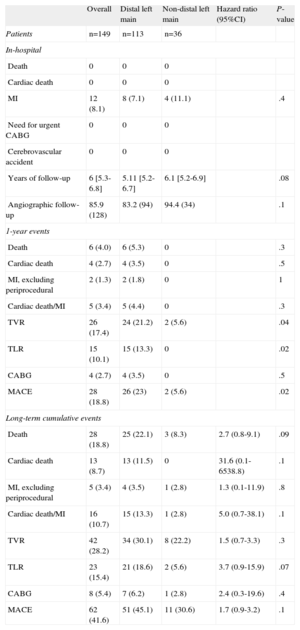

Clinical follow-up information beyond 5-years was obtained in 148 eligible patients (99.3%). Table 3 illustrates the in-hospital, 1-year and cumulative long-term clinical outcomes. No in-hospital deaths, ST or need for an emergency CABG were reported, while the incidence of peri-procedural MI was 8.1% of the overall population without significant differences between distal and ostial/body ULMCA disease (7.1% vs 11.1%; P=.4).

In-hospital, 1-Year and Long-term Outcomes

| Overall | Distal left main | Non-distal left main | Hazard ratio (95%CI) | P-value | |

| Patients | n=149 | n=113 | n=36 | ||

| In-hospital | |||||

| Death | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Cardiac death | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| MI | 12 (8.1) | 8 (7.1) | 4 (11.1) | .4 | |

| Need for urgent CABG | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Cerebrovascular accident | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Years of follow-up | 6 [5.3-6.8] | 5.11 [5.2-6.7] | 6.1 [5.2-6.9] | .08 | |

| Angiographic follow-up | 85.9 (128) | 83.2 (94) | 94.4 (34) | .1 | |

| 1-year events | |||||

| Death | 6 (4.0) | 6 (5.3) | 0 | .3 | |

| Cardiac death | 4 (2.7) | 4 (3.5) | 0 | .5 | |

| MI, excluding periprocedural | 2 (1.3) | 2 (1.8) | 0 | 1 | |

| Cardiac death/MI | 5 (3.4) | 5 (4.4) | 0 | .3 | |

| TVR | 26 (17.4) | 24 (21.2) | 2 (5.6) | .04 | |

| TLR | 15 (10.1) | 15 (13.3) | 0 | .02 | |

| CABG | 4 (2.7) | 4 (3.5) | 0 | .5 | |

| MACE | 28 (18.8) | 26 (23) | 2 (5.6) | .02 | |

| Long-term cumulative events | |||||

| Death | 28 (18.8) | 25 (22.1) | 3 (8.3) | 2.7 (0.8-9.1) | .09 |

| Cardiac death | 13 (8.7) | 13 (11.5) | 0 | 31.6 (0.1-6538.8) | .1 |

| MI, excluding periprocedural | 5 (3.4) | 4 (3.5) | 1 (2.8) | 1.3 (0.1-11.9) | .8 |

| Cardiac death/MI | 16 (10.7) | 15 (13.3) | 1 (2.8) | 5.0 (0.7-38.1) | .1 |

| TVR | 42 (28.2) | 34 (30.1) | 8 (22.2) | 1.5 (0.7-3.3) | .3 |

| TLR | 23 (15.4) | 21 (18.6) | 2 (5.6) | 3.7 (0.9-15.9) | .07 |

| CABG | 8 (5.4) | 7 (6.2) | 1 (2.8) | 2.4 (0.3-19.6) | .4 |

| MACE | 62 (41.6) | 51 (45.1) | 11 (30.6) | 1.7 (0.9-3.2) | .1 |

CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; 95%CI, 95% confidence interval; MACE, major adverse cardiovascular events; MI, myocardial infarction; TLR, target lesion revascularization; TVR, target vessel revascularization.

Data are expressed as no. (%) or median [interquartile range].

At 1-year follow-up, 6 patients died (4%), 4 of them from cardiac causes (2.7%), while 2 patients experienced a MI (1.3%). Target vessel revascularization occurred overall in 26 (17.4%) patients with a significant difference between distal and ostial/body ULMCA (21.2% vs 5.6%; P=.02). TLR was required in 15 patients (10.1%) and all of these were in the distal ULMCA group (13.3% vs 0%; P=.02). On the basis of these events, MACE at 1-year occurred in 28 patients (18.8%) of the overall population with a higher frequency in the distal ULMCA group (23% vs 5.6%; P=.02).

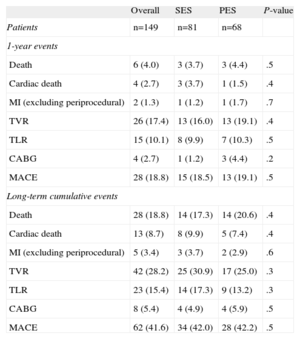

Similar results without significant differences in peri-procedural and 1-year clinical outcomes were obtained in the comparison between ULMCA patients treated with SES vs PES (Table 4).

Sirolimus-eluting Stent vs Paclitaxel-eluting Stent in Unprotected Left Main Stenosis

| Overall | SES | PES | P-value | |

| Patients | n=149 | n=81 | n=68 | |

| 1-year events | ||||

| Death | 6 (4.0) | 3 (3.7) | 3 (4.4) | .5 |

| Cardiac death | 4 (2.7) | 3 (3.7) | 1 (1.5) | .4 |

| MI (excluding periprocedural) | 2 (1.3) | 1 (1.2) | 1 (1.7) | .7 |

| TVR | 26 (17.4) | 13 (16.0) | 13 (19.1) | .4 |

| TLR | 15 (10.1) | 8 (9.9) | 7 (10.3) | .5 |

| CABG | 4 (2.7) | 1 (1.2) | 3 (4.4) | .2 |

| MACE | 28 (18.8) | 15 (18.5) | 13 (19.1) | .5 |

| Long-term cumulative events | ||||

| Death | 28 (18.8) | 14 (17.3) | 14 (20.6) | .4 |

| Cardiac death | 13 (8.7) | 8 (9.9) | 5 (7.4) | .4 |

| MI (excluding periprocedural) | 5 (3.4) | 3 (3.7) | 2 (2.9) | .6 |

| TVR | 42 (28.2) | 25 (30.9) | 17 (25.0) | .3 |

| TLR | 23 (15.4) | 14 (17.3) | 9 (13.2) | .3 |

| CABG | 8 (5.4) | 4 (4.9) | 4 (5.9) | .5 |

| MACE | 62 (41.6) | 34 (42.0) | 28 (42.2) | .5 |

CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; MACE, major adverse cardiovascular events; MI, myocardial infarction; PES, paclitaxel-eluting stent; SES, sirolimus-eluting stent; TLR, target lesion revascularization; TVR, target vessel revascularization.

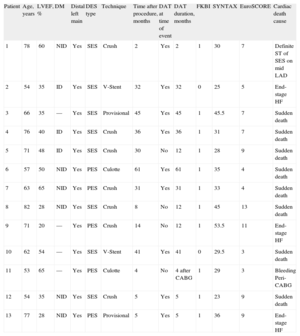

Data are expressed as no. (%).

At a median follow-up 6-years (interquartile range 5.3–7.8), 28 patients (18.8%) had died. Among them, 13 (8.7%) were adjudicated as cardiac deaths and all of these were in the distal ULMCA cohort. Table 5 illustrates the characteristics of patients who died from a cardiac cause during the follow-up period. Interestingly, no patient in the ostial/body group died from a cardiac cause. Five (3.4%) patients experienced an MI and no differences were found between the distal vs ostial/body lesions (3.5% vs 2.8%; P=1).

Main Clinical and Procedural Characteristics of Patients That Experienced Cardiac Death at Long-term Follow-up

| Patient | Age, years | LVEF, % | DM | Distal left main | DES type | Technique | Time after procedure, months | DAT at time of event | DAT duration, months | FKBI | SYNTAX | EuroSCORE | Cardiac death cause |

| 1 | 78 | 60 | NID | Yes | SES | Crush | 2 | Yes | 2 | 1 | 30 | 7 | Definite ST of SES on mid LAD |

| 2 | 54 | 35 | ID | Yes | SES | V-Stent | 32 | Yes | 32 | 0 | 25 | 5 | End-stage HF |

| 3 | 66 | 35 | — | Yes | SES | Provisional | 45 | Yes | 45 | 1 | 45.5 | 7 | Sudden death |

| 4 | 76 | 40 | ID | Yes | SES | Crush | 36 | Yes | 36 | 1 | 31 | 7 | Sudden death |

| 5 | 71 | 48 | ID | Yes | SES | Crush | 30 | No | 12 | 1 | 28 | 9 | Sudden death |

| 6 | 57 | 50 | NID | Yes | PES | Culotte | 61 | Yes | 61 | 1 | 35 | 4 | Sudden death |

| 7 | 63 | 65 | NID | Yes | PES | Crush | 31 | Yes | 31 | 1 | 33 | 4 | Sudden death |

| 8 | 82 | 28 | NID | Yes | SES | Crush | 8 | No | 12 | 1 | 45 | 13 | Sudden death |

| 9 | 71 | 20 | — | Yes | PES | Crush | 14 | No | 12 | 1 | 53.5 | 11 | End-stage HF |

| 10 | 62 | 54 | — | Yes | SES | V-Stent | 41 | Yes | 41 | 0 | 29.5 | 3 | Sudden death |

| 11 | 53 | 65 | — | Yes | PES | Culotte | 4 | No | 4 after CABG | 1 | 29 | 3 | Bleeding Peri-CABG |

| 12 | 54 | 35 | NID | Yes | SES | Crush | 5 | Yes | 5 | 1 | 23 | 9 | Sudden death |

| 13 | 77 | 28 | NID | Yes | PES | Provisional | 5 | Yes | 5 | 1 | 36 | 9 | End-stage HF |

CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; DAT, dual antiplatelet therapy; DES, drug-eluting-stent; DM, diabetes mellitus; EuroSCORE, European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation; FKBI, final kissing balloon inflation; HF, heart failure; ID, insulin-dependent; LAD, left anterior descending artery; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; NID, non-insulin-dependent; PES, paclitaxel-eluting stent; SES, sirolimus-eluting stent; ST, stent thrombosis; SYNTAX, Synergy Between Percutaneous Coronary Intervention With TAXUS and Cardiac Surgery.

Of interest, the Kaplan-Meier curves for cardiac death/MI remained fairly flat after the third year and there were only 2 cardiac events during the last year.

Throughout the entire follow-up period, TLR was performed in 23 patients (15.4%), of whom 21 (18.6%) were in the distal and 2 (5.6%; P=.06) were in the ostial/body group; 14 patients (17.3%) were in the SES and 9 (13.2) were in the PES group (P=.3) (Table 4). Among the 23 patients who underwent TLR, 8 (34.7%) needed surgical revascularization and 7 of these were in the distal group. Among the 8 patients that required CABG at follow-up, 7 had a multivessel with distal ULMCA bifurcation disease treated with 4.7 (2.6) DES implantations. Of the patients with distal ULMCA disease, 2/7 had a trifurcation involvement and both were treated with 3 DES implantations at the trifurcation site. Half (4/8) of the patients undergoing CABG during follow-up were asymptomatic with evidence of diffuse restenosis at routine follow-up angiography, while the remaining patients underwent angiography because of unstable angina. All the CABGs were performed electively. One peri-CABG death was reported because of bleeding complications while 1 patient experienced a stroke. At the last clinical contact, 6/7 patients who survived CABG were still alive and of these, 4 out of 6 were free from angina. Target vessel revascularization occurred in 42 (28.2%) patients in the overall population (30.1% distal vs 22.2% ostial/body; P=.4).

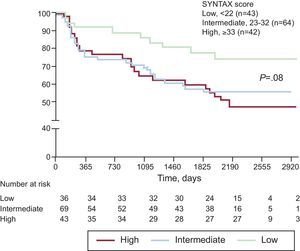

Kaplan-Meier survival curves for MACE and cardiac death/MI are presented for the distal and ostial/body ULMCA groups in Figures 1 and 2, respectively. A trend was observed for a lower 6-year MACE rate in patients with low SYNTAX score (≤22) as compared to intermediate (23-32) and high (≥33) scores (74% low vs 56% intermediate vs 48% high; P=.08), as shown in Figure 3.

Academic Research Consortium definite and/or probable ST was adjudicated in 2 (1.3%) patients (1 definite and 1 probable ST). The definite ST was a late ST (3.9 months after the index procedure) and occurred in a distal ULMCA lesion treated with PES implantation utilizing the crush technique. The ST presented as an anterior MI successfully treated with repeat PCI. Probable late ST was adjudicated in a patient who presented with a fatal MI, 3 months after crush stenting with SES on the distal ULMCA. Both the definite and the probable ST occurred while the patients were on dual antiplatelet therapy. Possible ST at 6-year follow-up was adjudicated in 8 patients (5.4%). Notably, only 38.3% of the patients were still taking dual antiplatelet therapy at the time of last clinical follow-up. Definite and probable ST are reported in Table 6.

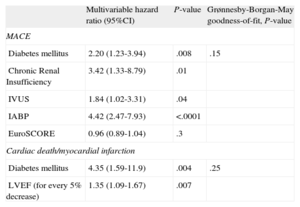

Table 7 shows the results of the Cox multivariable analysis to identify the predictors for MACE and for cardiac death and MI. At a median of 6-years’ follow-up, diabetes, chronic renal insufficiency, IVUS and IABP were independent predictors for MACE, while diabetes and EF were identified as predictors for cardiac death and MI.

Multivariable Analysis for Predictors of Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events and Cardiac Death/Myocardial Infarction After Drug-eluting Stent Implantation in Unprotected Left Main Coronary Artery Disease

| Multivariable hazard ratio (95%CI) | P-value | Grønnesby-Borgan-May goodness-of-fit, P-value | |

| MACE | |||

| Diabetes mellitus | 2.20 (1.23-3.94) | .008 | .15 |

| Chronic Renal Insufficiency | 3.42 (1.33-8.79) | .01 | |

| IVUS | 1.84 (1.02-3.31) | .04 | |

| IABP | 4.42 (2.47-7.93) | <.0001 | |

| EuroSCORE | 0.96 (0.89-1.04) | .3 | |

| Cardiac death/myocardial infarction | |||

| Diabetes mellitus | 4.35 (1.59-11.9) | .004 | .25 |

| LVEF (for every 5% decrease) | 1.35 (1.09-1.67) | .007 | |

95%CI, 95% confidence interval; EuroSCORE, European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation; IABP, intra-aortic balloon-pump; IVUS, intravascular ultrasound; LVEF, left ventricle ejection fraction; MACE, major adverse cardiovascular events.

The main findings of this report of long-term outcomes following DES implantation for ULMCA are as follows: a) long-term safety was maintained with low rates of cardiac death and MI, as well as definite/probable ST; b) long-term outcomes were favorable in ostial and mid-shaft ULMCA lesions compared to distal bifurcation lesions; c) the TLR rate was satisfactory in a cohort predominantly composed of patients with distal ULMCA lesions associated with multivessel disease; d) implantation of PES or SES in ULMCA lesions was safe and effective, providing comparable long-term clinical outcomes, and e) diabetes and EF were independent predictors of cardiac death and MI at very long-term follow-up.

According to current American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association and European Society of Cardiology guidelines, CABG is the recommended treatment for ULMCA.1,17 However, in European daily practice, 4.6% of patients undergoing coronary angiography have ULMCA disease and 58% of these are treated by PCI.18 In Spain, the significant increase in PCIs for ULMCA disease continued, now standing at 2271 interventions. This is 15% more than last year, representing 3.5% of all PCIs (3.1% in 2009).19 Encouraging results have been recently reported for the ULMCA subgroup analysis of the randomized SYNTAX trial, especially in patients with isolated ostial or mid-shaft ULMCA stenosis or ostial/body ULMCA disease associated with single-vessel disease.3,20 As reported at 1-year follow-up, PCI with PES implantation resulted in similar major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular event rates as compared to CABG for patients with low and intermediate SYNTAX scores, whereas event rates were significantly higher for PCI in the high score (>32) group.3,20 However, because of the hypothesis-generating nature of subgroup analysis, these results cannot be considered to be clinically directive. In this context, recent data from the PRE-COMBAT (PREmier of Randomized COMparison of Bypass Surgery Versus AngioplasTy Using Sirolimus-Eluting Stent in Patients With Left Main Coronary Artery Disease),21 randomized trial involving Korean patients with ULMCA stenosis showed that PCI with SES was non-inferior to CABG with respect to the primary end-point of MACE and cerebrovascular event (a composite of death from any cause, MI, stroke, or ischemia-driven target vessel revascularization at 1 year). However, because the power of the trial was lower than expected and because the non-inferiority margin was wide, other results from adequately powered trials are still needed.21

In addition to subgroup analysis of randomized trials, data from non-randomized comparative studies of PCI vs CABG in ULMCA disease have nevertheless consistently demonstrated similar risk-adjusted event rates for hard clinical endpoints, such as death and MI up to 5 years of clinical follow-up.11,12

The currently available evidence gave sufficient support for the European guidelines to change the indication to class IIa for PCI in ostial or shaft ULMCA lesions that are isolated or associated with single-vessel disease.17 The data we report, at a median of 6-years’ follow-up, show a cumulative cardiac death and MI rate of 10.7%. These results are comparable to those obtained from other registries of ULMCA stenting with similar sample sizes but shorter follow-up periods.8,22,23 In the DES cohort of the LE MANS (Left Main Coronary Artery Stenting) Registry (94 patients with distal ULMCA involvement in 72.8% of cases), Buszman et al. reported an incidence of death and MI of 9.6% and 13.8% respectively at a median follow-up of 3.8 years.

The RESEARCH and T-SEARCH registries showed that ULMCA PCI with DES was associated with death and MI rates of 33.1% and 2% respectively, at 4-years’ follow-up. Recent data from a Spanish registry of 226 patients with ULMCA stenosis not suitable for CABG and treated with PCI showed cardiac death and MI rates of 19.2% and 8.4% at a median of 3-years of follow-up.8

The long-term safety of ULMCA PCI with DES was also suggested by the definite/probable ST rate of 1.3% reported in this registry. This incidence is consistent with published results from registries of ULMCA treated with DES. In a multicenter international registry of 731 patients, a cumulative incidence of 0.95% of definite ST was reported at 29 months of follow-up whereas a 1.7% rate of definite ST was recently reported in a Korean registry at 5 years’ follow-up.24,25 Even if our population was smaller than the aforementioned studies, the low ST rates are quite reassuring considering the longer clinical follow-up and the clinical and angiographic risk profile of the patients included in the analysis (EuroSCORE>6 in 31.5%, distal lesion in 75.8% and multivessel disease in 47%).

Lesion location appeared to have a strong influence on medium- and long-term outcomes following ULMCA PCI with DES. It is known from the literature that ULMCA lesions not involving the distal bifurcation are associated with favorable outcomes in terms of death, MI and repeat revascularization as compared to the more common ULMCA bifurcation lesions.26,27 Our study confirms that even at long-term follow-up, clinical outcomes were better following PCI for ostial and mid-shaft lesions as compared to distal bifurcation lesions (6-year cardiac death: 0% ostial/body vs 11.5% distal; TLR: 18.6% vs 5.6%). Among ULMCA PCI studies, the stenting approach for bifurcation disease has varied widely according to the operators’ discretion and institutional standards, making comparison difficult. However, an important caveat that needs to be taken into account when interpreting these data is the complexity of the bifurcation lesions treated in our cohort: 79.6% of bifurcations had significant disease in both branches requiring a 2-stent approach in 63.8%, of which the “early” crush technique was performed in 58.3% of these cases.

Although previous data showed that the use of an “early” crush technique in non-ULMCA bifurcation lesions was associated with an increased risk of restenosis when compared with a “modern” crush approach with less stent protrusion,28,29 double-step kissing balloon optimization (only 65.5% in this series) or high pressure post-dilatation of the side branch. Unfortunately no randomized data are currently available regarding the best stenting approach in complex ULMCA distal bifurcation.

An additional factor which needs to be considered is that most patients with distal ULMCA lesions have more associated multivessel disease, as shown by a higher SYNTAX score after exclusion of the ULMCA lesion (Table 1). Furthermore, the TLR rate of 15.4% in this study may have been influenced by our initial protocol of routine angiographic follow-up to detect early ULMCA stent restenosis, which was performed in 85.9% of patients. Indeed, many of the early TLR may have been angiographically rather than clinically driven. However, it is interesting to note that there were only 9 new TLR from 1-6 years, suggesting that at least in this preliminary experience, a late catch-up phenomenon was not observed.

Regarding the impact of DES selection, we found no differences in the long-term need for TLR between PES vs SES (13.3% vs 17.2%; P=.3). This finding is consistent with the results of the randomized ISAR-LEFT MAIN trial which showed that ULMCA PCI with either PES or SES was associated with similar rates of TLR through 2-years of follow-up (9.2% PES vs 10.7% SES; P=.47).30

Despite the favorable results with first-generation DES in the ULMCA setting, the need for reintervention as well as ST remains unresolved. In this context the use of a newer generation everolimus-eluting stent has recently been shown to be safe, with a 1-year cardiac death and definite/probable ST rates of 1.2% and 0.6%, and effective, with TLR and target vessel revascularization rates of 2.9% and 7% respectively.31 Randomized clinical trials with prolonged follow-up comparing PCI with new generation DES vs CABG are warranted to establish the role of these new devices in the ULMCA subset.

Finally, the low rate of IVUS guidance in this study may also negatively impact on outcomes. However, these data are a reflection of our initial experience of treating ULMCA with DES implantation prior to the publication of studies such as the MAIN COMPARE sub-analysis,32 which suggested that IVUS-guided ULMCA PCI improves outcomes, reducing 3-year mortality. Although randomized data showing an impact of IVUS-guidance in reducing TLR are currently unavailable, we strongly believe in recommending that ULMCA stenting should be performed under IVUS guidance and we currently do so in the majority of patients with ULMCA disease treated in our center.

Regarding the findings that IVUS and IABP were predictors of MACE, we believe that these 2 parameters are likely to be confounders because they were more frequently associated with high-risk patients (complicated PCIs, distal ULMCA bifurcation/trifurcation lesions, EF≤40%, long lesions [>40mm] involving bifurcations on left anterior descending artery, and ULMCA disease associated with chronic total occlusions of other vessels). Indeed, in the present study, IABP was utilized in patients with worse clinical and angiographic characteristics (left main coronary artery plus 3-vessel disease: 26.8% IABP vs 14.1% no-IABP; P=.04; SYNTAX score>33: 37.2% vs 13.2%; P=.001; EF≤40%: 50% vs 15%; P=.001; 2-stent approach: 29.2% vs 11.7%; P=.007) compared with the no-IABP group, which probably impacted negatively on long-term outcomes.

Diabetes and low left ventricular EF are known to be predictors of cardiac death and MI after PCI33,34 even for ULMCA disease.35 Similarly, in our study, diabetes and EF predicted cardiac death and MI at longer-term follow-up and these variables should be taken into account when choosing a revascularization strategy in patients with ULMCA and multivessel disease.

LimitationsThis was a retrospective, observational, single-center study that represents an experience of unselected consecutive patients with ULMCA disease undergoing PCI with DES, reflective of everyday clinical practice. Despite the promising results, definitive conclusions cannot be drawn on the best revascularization option in ULMCA disease. Furthermore, the small number of patients analyzed and the low percentage (25%) of IVUS-guidance may have influenced the results.

ConclusionsThe results of this study show that PCI for ULMCA stenosis with first generation DES was associated with low cardiac death, MI and ST rates at a median of 6-years’ follow-up in patients with lesions located at ostial/body of the ULMCA. The TLR rate suggests that procedural (such as IVUS-guided stent optimization, better lesion preparation and post-dilatation or other technical approaches to distal ULMCA stenting), technological improvements (such as “new generation” DES or stent platform) and more effective pharmacology (new antiplatelet drugs) are still needed to reduce event rates, particularly in more severe lesions such as complex distal ULMCA bifurcation associated with triple-vessel disease, in which CABG still remains the standard of care for most of the patients.

Conflicts of interestNone declared.