To the Editor,

Cardiac perforation is rare after implantation of pacing or defibrillation wires and mainly occurs when the leads are inserted into the myocardial wall. Perforation is increasingly common, is usually associated with the use of small-caliber active fixation leads, and can occur beyond the first few days (subacute) or even more than a month after implantation (late).1 The most common clinical manifestations are cardiac tamponade, hemopericardium, pneumothorax or hemothorax, or diaphragmatic or pectoral stimulation, always accompanied by data indicating lead malfunction. Radiology and echocardiography can confirm the perforation by revealing progression of the lead beyond the cardiac silhouette or indirectly visualizing the presence of pericardial or pleural effusion. On occasion, the clinical presentation may be atypical and the most common diagnostic techniques do not confirm an accurate diagnosis that would help the clinician make the safest, most appropriate therapeutic decision.

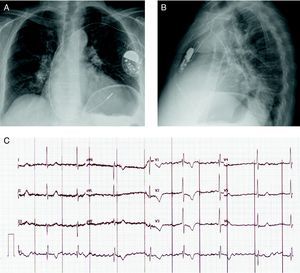

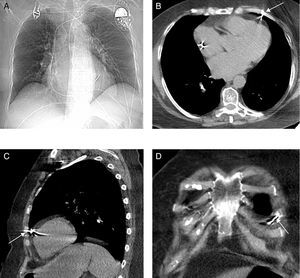

A 72-year-old woman with hypertension and chronic atrial fibrillation was admitted for a heart failure syndrome in relation to slow ventricular response (40 bpm) in the absence of secondary causes. Ten years earlier, the patient had been treated by surgery and radiotherapy for breast cancer. Echocardiography revealed mild left ventricular hypertrophy with preserved systolic function, as well as moderate degenerative mitral regurgitation with pulmonary hypertension. A single-chamber pacemaker system was implanted, with the generator placed at the left prepectoral subcutaneous level (Identity™ ADx SR 5180, St. Jude Medical) with a 6-French active fixation lead (Tendril™ ST 1888TC, St. Jude Medical) implanted in the right ventricular free wall (Figure 1), where the best parameters were achieved (threshold, 1 V×0.5 ms; impedance, 1196 ohms; R wave, 8.6 mV). The pacemaker was programmed in VVIR mode with a lower threshold of 60 bpm. The patient remained asymptomatic with continuous pacemaker capture. Five days after the procedure, the patient consulted for the sudden onset of focal chest pain in the precordial region, which she described as repetitive stabbing; there was no hemodynamic deterioration. However, the electrocardiogram showed pacemaker capture and sensing failure, with a decrease in the impedance measured (Figure 1C). An emergency echocardiography ruled out pericardial effusion but failed to visualize the tip of the lead. The chest X-ray ruled out pleural effusion or pneumothorax and showed the ventricular lead in an apparently normal position (Figure 2A). Despite the findings of the chest X-ray and the echocardiogram, a multislice computed tomography (16 detector rows) study was performed to define the actual position of the ventricular lead prior to surgery. The study revealed that the lead perforated the myocardium, crossed the pericardial fat, pericardium and epicardial fat, and pulmonary parenchyma, and impacted against the periosteum of a rib (Figure 2B-D) but did not cause pleural or pericardial effusion. Due to the possibility of late development of one of these manifestations, a decision was made to withdraw the lead. Based on the tomography findings, the lead was removed in the cardiac surgery operating theater under transesophageal echocardiography control; no pericardial effusion or other sequelae were observed. Several days later, a new pacemaker system was implanted in the right ventricular apex without incident.

Figure 1. Chest X-ray after implantation in posteroanterior position (A) and lateral position (B). C: 12-lead electrocardiogram at the onset of chest pain, showing failure of pacemaker capture and sensing (asynchronous at 60 bpm with no ventricular capture).

Figure 2. A: chest X-ray following the onset of pain and the evidence of pacemaker malfunction; note the similar position of the lead compared to postimplantation. B, C, and D: computed tomography of the thorax in which no signs of pericardial effusion, pleural effusion, or pneumothorax are observed; the right ventricular free wall is perforated by the lead, which crosses the pericardial fat, pericardium and epicardial fat, makes contact with the pulmonary parenchyma (lingula), and remains lodged next to the costal arch.

In this clinical case, the absence of pleural or pericardial effusion could have been favored by rapid detection of the problem and the potential influence of the radiotherapeutic treatment received by the patient years earlier. The case underscores the usefulness of computed tomography to define lead location accurately, particularly in patients with an atypical presentation and in whom the usual techniques cannot confirm or define cardiac perforation and the potential seriousness of the process could be underestimated. In addition, because contrast studies are not needed to obtain the information required, the lower radiation dose received by the patient is compensated by the potential benefits of its diagnostic capacity.

Corresponding author: maapalomares@secardiologia.es