Keywords

INTRODUCTION

The use of implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICD) has proven to be effective for the primary and secondary prevention of sudden cardiac death (SCD). The results of numerous published studies have allowed the principal indications for ICD use to be established in the clinical guidelines for management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias or at risk for SCD.1,2 However, the increased use of ICDs has raised questions about their efficacy outside of the context of clinical trials, as well as about appropriate selection of patients for ICD placement, access to treatment, safety, and cost-effectiveness.3 Patient registries may help to fill gaps in the literature to address these issues or to assess the applicability of the clinical guidelines to nonselected patient populations.

In this report, we present the data available on ICD placement from the Spanish ICD Registry for 2008. Data for the registry were collected from the majority of hospitals in Spain that implant ICDs. As for previous official reports,4-7 this report was prepared by the Working Group on ICDs (WGICD) within the Electrophysiology and Arrhythmia Section of the Spanish Society of Cardiology (SEC).

The main aim of the registry is to determine how ICDs are currently used in Spain in terms of indications, clinical characteristics of the patients, implant parameters, types of device, device programming, and complications associated with the procedure.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

The registry data were obtained using a data collection form available on the SEC web page (http://profesionales. secardiologia.es/seccionesy-grupos/electrofisiologia-y-arritmias.html). This form was completed directly and voluntarily by each implant team, during or after ICD placement, with the collaboration of staff from the manufacturer of the ICD, and was sent to SEC by fax or e-mail. This year, as in the first 4 years of the registry, all data used to prepare the report were collected prospectively, since in previous reports retrospective data collection provided little additional data (1.8% additional data in 2007) and lower quality information (a larger number of incomplete fields in retrospectively completed forms).

Members of the SEC staff entered the data into the database of the Spanish ICD Registry. The data were cleaned by a SEC computer specialist and a member of the WG-ICD. The authors of this article were responsible for analyzing the data and preparing the manuscript.

The population data, both for the country as a whole and according to autonomous community and province, that were used to calculate rates per million population were obtained from the estimates reported for the period up to January 1, 2008, by the Spanish National Institute of Statistics (http://www.ine.es).8

To calculate the representativeness of the registry, we estimated the proportion of all the implants and replacement procedures performed in Spain in 2008 that had been reported. The total number was based on data provided by the device manufacturers to the European Confederation of Medical Suppliers Associations (EUCOMED).9

Where different medical conditions or clinical arrhythmias were reported for the same patient, only the most serious condition was included for analysis.

The percentages calculated for each variable analyzed were based on the total number of implants for which information on that variable was available.

Statistical Analysis

The numerical results were expressed as means (SD) or median (interquartile range), according to the distribution of the data. Continuous variables were compared by analysis of variance (ANOVA) or Kruskal-Wallis test. Qualitative variables were compared using the c2 test. The relationship between number of implants and implanting hospitals per million inhabitants and between the total number of implants and the number of implants for primary prevention in each hospital were assessed by linear regression analysis. The statistical significance of the trend towards use of ICDs in primary rather than secondary prevention was assessed by Mantel-Haenszel c2 test. Statistical significance was set at P less than .05. The statistical analysis was carried out using the JMP statistical software program (version 5.0.1).

RESULTS

Response rates for the different fields of the data collection form ranged from 60% (functioning of the original electrodes in the case of ICD replacement) to 97.7% (name of implanting hospital), although in most fields the response rate was in excess of 80%.

Implanting Hospitals

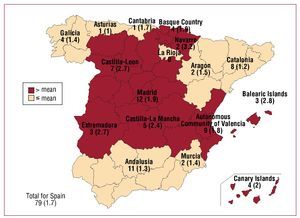

A total of 117 hospitals that performed ICD placement contributed data to the registry (29 more than in 2007) (Table 1). Of those, 79 were public hospitals (11 more than in 2007). Figure 1 shows the total number of public hospitals and the number of public hospitals per million inhabitants that contributed data to the registry in each autonomous community.

Figure 1. Number of Spanish public implanting hospitals (rate per million population) according to autonomous community in 2008. Four public-private hospitals are included.

Total Number of Implants

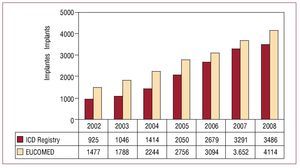

In total, 3486 implants (first implantations and replacements) were included in the registry for 2008. Based on a total of 4114 implants performed in that year (according to data from EUCOMED), this represents 84.7% of all ICD implants performed in Spain. Figure 2 shows the total number of implants included in the registry alongside those estimated by EUCOMED for the last 7 years.

Figure. 2. Total number of implants reported to the registry and estimated by the European Confederation of Medical Suppliers Associations (EUCOMED) from 2002 to 2008. ICD indicates implantable cardioverter-defibrillator.

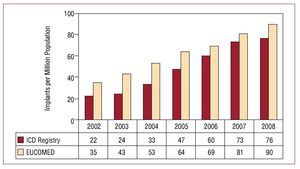

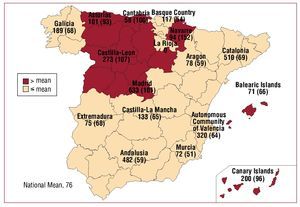

The total number of implants included in the registry per million inhabitants was 76. The total number of implants per million inhabitants according to EUCOMED data was 90. Figure 3 shows the increase in the number of implants per million inhabitants reported to the registry and that estimated by the EUCOMED for the last 7 years. Table 1 shows the number of implants reported to the registry by each implanting hospital. Figure 4 shows the number of implants performed in each autonomous community and reported to the registry in 2008, along with the number of implants reported per million inhabitants. Table 2 shows the number of implants reported to the registry according to province and autonomous community in which the patient resided and the number per million population.

Figure. 3. Total number of implants per million population reported to the registry and estimated by the European Confederation of Medical Suppliers Associations (EUCOMED) from 2002 to 2008. ICD indicates implantable cardioverter-defibrillator.

Figure 4.Implants reported to the registry in 2008 (rate per million population), according to autonomous community. Both first implants and replacements are included.

Most of the implants reported were performed in public hospitals (3252), representing 95.5% of the 3406 reports included in the registry for which data on implanting hospital were available.

There was a trend towards a weak correlation between the number of implanting hospitals per million population and the number of ICDs implanted per million population in each autonomous community (r2=0.22; P=.07).

First Implants Versus Replacements

Information on whether ICD placement corresponded to a first implant or a replacement was available in 3170 of the forms received (90.9%). The number of first implants was 2477, representing 78.1% of all implants reported. A total of 54 first implants per million population were reported to the registry. The number of replacements performed was 693 (21.9%).

Age and Sex

The mean (SD) age of the patients who received either first ICD implants or replacements was 61.7 (12) years (range, 5-89 years). When only first implants were considered, the mean (SD) age was 61.4 (12) years (range, 5-89 years). The majority of implants were performed in male patients, who accounted for 82.9% of all implants and 81.3% of first implants.

Underlying Heart Disease, Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction, Functional Class, and Baseline Rhythm

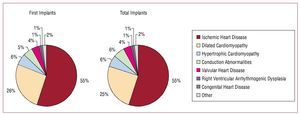

The proportions of patients with different underlying heart diseases were very similar in both the patients who received first implants and in the group as a whole (Figure 5). The most common condition was ischemic heart disease, followed by dilated cardiomyopathy, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, and primary conduction abnormalities (Brugada syndrome, idiopathic ventricular fibrillation, and long QT syndrome). These were followed by valvular heart disease and arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. Few cases of ICD placement were recorded in patients with idiopathic ventricular tachycardia, noncompaction cardiomyopathy, sarcoidosis, or other rare forms of heart disease.

Figure. 5.Underlying heart diseases reported to the registry (first implants and total implants).

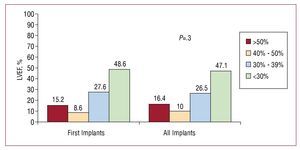

In terms of left ventricular systolic function, 48.6% of patients who received a first ICD had a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) less than 30%. A LVEF between 30% and 39% was reported for 27.6% of patients. The least numerous patients were those with mild dysfunction, with LVEF between 40% and 49%. Similar proportions were observed for the total number of implants performed (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of the patients in the registry (first implants and total implants).

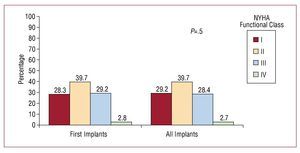

Almost 40% of patients were in New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class II. They were followed in number by the group of patients in NYHA functional classes III and I, whereas only a very small number of patients were in functional class IV. There were no significant differences between all implants performed and first implants considered alone (Figure 7).

Figure 7. New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class of the patients in the registry (first implants and total implants).

The majority of the patients in the first implant group (81.2%) were in sinus rhythm, whereas 14.5% had atrial fibrillation, 2.7% had pacemaker rhythm, and the rest exhibited other rhythms (atrial flutter or other atrial arrhythmias). The percentages for the overall group were 79.3%, 14.5%, and 4.5%, respectively.

Clinical Arrhythmia Necessitating ICD Placement, Presentation, and Laboratory-Induced Arrhythmia

The most common group of patients among those who received a first implant were those without documented clinical arrhythmia (41.7%). They were followed in number by those with sustained monomorphic ventricular tachycardia (SMVT) and nonsustained ventricular tachycardia. In the overall group, 37.2% of patients had no documented arrhythmia, as a result of the larger proportion of patients with sustained arrhythmias. The differences in the type of arrhythmias in the group of patients with first implants compared with the overall group were statistically significant (P<.01) (Figure 8).

Figure 8. Clinical arrhythmia in the patients included in the registry (first implants and total implants). VF/ MVT indicates ventricular fibrillation/ monomorphic ventricular tachycardia; SMVT, sustained monomorphic tachycardia; NSVT, nonsustained ventricular tachycardia.

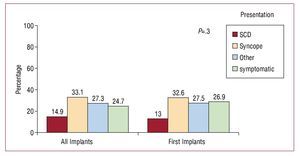

The most common clinical presentation, both in the overall group and in the group of patients who received first implants, was syncope, followed by "other symptoms" and the absence of symptomatic arrhythmias. There were no statistically significant differences in the clinical presentation between patients receiving first implants and the overall group (Figure 9).

Figure 9. Clinical presentation of arrhythmia in the patients included in the registry (first implants and total implants). SCD indicates sudden cardiac death.

Information on the use of an electrophysiology study was provided in 70% of patients receiving first implants. An electrophysiology study was performed in 578 of the 1731 first implants (33.4%) for which this information was provided. In most cases it was performed in patients with prior history of infarction or dilated cardiomyopathy and SMVT, and in patients with previous infarction and syncope; SMVT was the most commonly induced arrhythmia (43%). In 33% of cases, no sustained arrhythmia was induced.

Indications

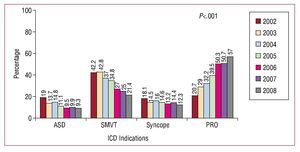

In 57% of first implants, the indication for ICD placement was primary prevention. There has been an increasing trend in ICD placement for primary prevention since the beginning of the second phase of the registry, increasing from 20.7% of the indications reported to the registry in 2002 to 57% in 2008. The progressive increase in use for primary prevention and the gradual reduction in implantation for secondary prevention between 2002 and 2008 was statistically significant (P<.001) (Figure 10).

Figure 10. Changes in the major indications for implantable cardioverterdefibrillators (first implants) between 2002 and 2008. ASD indicates aborted sudden death; PRO, prophylactic indication; Syncope, syncope without electrocardiographic documentation of arrhythmia; SMVT, sustained monomorphic ventricular tachycardia.

Patients with ischemic heart disease represented the largest group. In those patients, primary prevention accounted for almost half of all indications (49.3%), representing a clear increase over the previous year (41.8%). In 32.6% of cases in which implantation was carried out for primary prevention, ICD placement involved a device with CRT capability (ICD-CRT).

The next most frequent indication was for primary prevention in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy (58.3% of implants in patients with this condition were for primary prevention, also representing an increase over the percentage in 2007 [55.2%]). Of those, 64% of cases involved ICD-CRT placement.

In patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, Brugada syndrome, long QT syndrome, or congenital heart disease, more than 50% of implantations were for primary prevention. In contrast, in patients with valve disease and arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy, ICD placement was more commonly performed for secondary prevention.

There was a statistically significant correlation between the total number of first implants in a hospital and the number that were performed for primary prevention (r2=0.58; P<.01).

Table 3 details the changes in the indications associated with the principal types of heart disease over the last 4 years (those with the largest representation in the registry).

Setting and Personnel

Information on setting and personnel was available for 92.3% and 93.2%, respectively, of the implants reported to the registry. In 67.7% of cases, ICD placement was performed in an electrophysiology laboratory and in 32.3% of cases in the operating theater. There were no reports of implants performed in other settings.

The intervention was performed by a cardiac electrophysiologist in 73.6% of cases. In 21.3% of cases it was performed by a heart surgeon and in 5.1% by another specialist. ICD placement was performed by cardiac electrophysiologists in 49 public hospitals (62%), by heart surgeons in 13 (16.4%), by other specialists (principally internal medicine) in 8, by surgeons and electrophysiologists in 7, and by electrophysiologists and other specialists in 2.

Positioning of the Generator

In the majority of cases, the generator was implanted in a subcutaneous pectoral position (88.7% of all implants and 91.7% of first implants). Submuscular pectoral placement was employed in 11% of all implants and in 8.2% of first implants. Abdominal placement was used in 2 first implants and 11 replacements (<0.1% of first implants and 0.3% of all implants).

Device Type

When all the implants (first implants and replacements) were analyzed, the percentages of single-chamber ICDs, dual-chamber ICDs, and ICD-CRT devices were 48.1%, 23.8%, and 28.1%, respectively. When only primary implants were evaluated, these proportions were 46.6%, 24.1%, and 29.3%, respectively.

According to data provided by the EUCOMED, in 2008, 1971 single-chamber ICDs (47.9%), 899 dual-chamber ICDs (21.9%), and 1244 ICD-CRT devices (30.2%) were implanted.

Reasons for Replacement. Substitution of Electrodes in Replacement Generators and Use of Additional Electrodes

Of the reported replacements, information on the reason for replacement was available in 70% of cases. Of these, 84.7% were due to battery depletion and the remainder were due to complications. Of the 74 replacements due to complications, 76.5% took place within the first 6 months after implantation.

Of the original electrodes, 14.5% were nonfunctioning. Of those, 76% were explanted.

ICD Programming

The most commonly employed antibradycardia pacing was VVI mode (50%). VVIR mode was used in 9% of the cases, DDD in 28%, DDDR in 9%, and other pacing modes in 4% of the cases (mainly modes selected to reduce the percentage of ventricular pacing in dual-chamber devices).

The device was programmed for ventricular antitachycardia pacing in 86% of cases, with a combination of ventricular and atrial pacing in 5%. Antitachycardia pacing was not programmed in 9% of implants.

Both ventricular and atrial defibrillation or cardioversion therapies were programmed in 7% of cases.

Complications

Three deaths during implantation (0.8/1000 procedures) were reported. Nine complications occurring during implantation were reported: 2 cases of cardiac tamponade and 7 unspecified.

DISCUSSION

The Spanish ICD Registry continues to maintain an acceptable representativeness (>84% in the last 3 years), and the data contained can therefore be considered a good reflection of the indications, clinical characteristics of the patients, implant parameters, types of device, programming, and complications associated with ICD placement in Spain, and a good indicator of the real-world situation relating to these factors.

Comparison with Previous Years. Increased Use for Primary Prevention

The most noteworthy finding in 2008 is the increase in the number of implants used for primary prevention compared with 2007, especially in the 2 largest groups of patients: in those with ischemic heart disease, for whom the proportion of implants for primary prevention has increased from 41% to almost 50%, and to a lesser degree in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy, for whom a greater increase had already been observed in the previous 2 years. The increase in use of ICDs for primary prevention has occurred progressively over the last 7 years, although with 3 significant steps. The first occurred between 2002 and 2003, probably due to the publication of the Multicenter Autonomic Defibrillator Implantation Trial II (MADIT II) study.10 The second, between 2005 and 2006, was largely related to the results of the Comparison of Medical Therapy, Pacing and Defibrillation in Heart Failure (COMPANION)11 and Sudden Cardiac Death in Heart Failure Trial (SCDHeFT)12 studies. Finally, the slightly less marked increase in 2008 is not associated with the publication of any significant studies. The impact of clinical trials and adherence to recommendations in clinical practice guidelines have been more gradual in Spain than in other countries in the European Union or in the United States, where the increase in the number of implants has been more rapid, especially for use in primary prevention.

The total number of implants reported to the registry and the number of implants per million population have continued to increase due to an increase in the total number of implants performed. In contrast, the percentage of the total number of implants estimated by EUCOMED that were reported to the registry was reduced from 90% in 2007 (similar to the Italian registry of the same year) to 84.7%.

The number of implanting hospitals also increased, whereas this number remained stable in 2007. This is explained by the increased number of arrhythmia units in Spain along with an increase in available personnel and resources.

There have been no significant changes in the epidemiologic characteristics of the patients, who remained similar in terms of mean age and the marked predominance of male patients. There were also no notable changes in terms of the type of heart disease leading to the decision to implant an ICD. Patients with severe or moderate-to-severe ventricular dysfunction and NYHA functional class II and III continue to be in the majority, with the gradual increase of previous years being maintained as a consequence of the increase in the number of prophylactic procedures.

In terms of the type of device, the proportion of single-chamber ICDs, dual-chamber ICDs, and ICD-CRT devices was similar to that found in 2007. There were no significant changes in terms of programming of antitachycardia pacing functions or the antibradycardia pacing mode.

Finally, there was a slight increase in the number of implants performed by electrophysiologists, who were responsible for almost three quarters of the procedures carried out.

Comparison With Other Countries

The EUCOMED data for 2008 include ICD and ICD-CRT implants for Austria, Belgium and Luxembourg, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom. The mean number of implants (ICD and ICD-CRT) per million population was 174, ranging from 90 in Spain to 367 in Germany. In addition to Germany, above average rates were reported for Italy (301), the Netherlands (288), Denmark (239), and Austria (204). Spain (90), Portugal (99), Greece (109), Norway (113), Sweden (113), and Finland (114) had the lowest number of implants per million population. Taking into account only ICDs with CRT, the mean number per million population was 53. Italy (134), Germany (103), the Netherlands (93), Austria (68), and Denmark (59) had above average rates, whereas Norway (22), Finland (25), Spain (27), Greece (28), and Portugal (31) were below average. The mean proportion of all ICDs that had CRT function was 30.5%; in Spain the percentage was 30% and ranged from 19.5% in Norway to 44.5% in Italy.

In September of 2008, the second report of the United States National ICD Registry was published, covering the period from 2006 to 2007.13 Although reporting of implants is obligatory for primary prevention but voluntary for other indications, 88% of implants are performed in hospitals that also report use for secondary prevention. Between January of 2006 and December of 2007, a total of 206 604 implants were reported. Of those, 78% were first implants, a proportion similar to that observed in the Spanish registry. The main difference compared with other registries is the high proportion of implants performed for primary prevention: 78.7% in the US registry compared with 57% in the Spanish registry. The mean age of patients was 68.1 (12.7) years, which is higher than observed in the Spanish registry, but with a slightly lower proportion of male patients (74%). The most frequent underlying condition was ischemic heart disease with prior history of infarction, which accounted for 54.9% of implants, followed by dilated cardiomyopathy (30.6%), both of which were quite similar to the percentages observed in the Spanish registry. Forty-six percent of patients had NYHA functional class III and the mean LVEF was 27.8% (11.1%). Of the devices implanted, 38.3% had CRT function and 39% were dual chamber, proportions that are higher than those observed in Spain. The implantation procedures were performed by electrophysiologists in 82.8% of cases, also a greater proportion than in the Spanish registry.

This year has seen the publication of the Italian registry for the period 2005 to 2007, which prospectively collects data from the EURID card.14 A total of 221 ICDs and ICD-CRTs were implanted per million population in 2007, a rate that is much higher than that observed in the Spanish registry. The rate of implantation for primary prevention was 55.7%, slightly lower than that observed for Spain in 2008 but higher than for 2007 (50.7%). The mean age of the patients (69 years) was also higher than in the Spanish registry. The underlying disease was ischemic heart disease in 37.7% of patients, dilated cardiomyopathy in 35.4%, myocardial hypertrophy in 2.6%, and valve disease in 1.6%. There was a noticeably higher rate of ischemic heart disease in the Italian registry compared with both the Spanish and US registries. In terms of the type of device implanted, 39.8% were ICDs with CRT, 31.7% were dual-chamber ICDs (both notably higher than in the Spanish registry), and 28.5% were single-chamber ICDs.

The most recent data published from the Danish registry are for 2007.15 In that year, 783 implants were performed (153 per million population) in the 5 implanting hospitals in Denmark. The mean age was 65.2 years and 82.3% of implants were performed in male patients.

The indication was ventricular tachycardia in 36.8% of cases and ventricular fibrillation in 22.2%. The most common underlying condition was ischemic heart disease in 32.7% and dilated cardiomyopathy in 18.3%. The most recent data published from the Portuguese registry were for 2006 and do not reflect the current situation in Portugal.16 The Latin American ICD Registry includes 507 patients in whom ICD devices from the same manufacturer were implanted in different Latin American countries.17 It includes data on mortality and hospital admissions over a mean follow-up period of 11 months. Finally, the design and preliminary data for the Ontario ICD Registry were also recently published.18 It is an obligatory longitudinal registry that prospectively includes not only the clinical characteristics of the patients and implants but also clinical course, and includes data on appropriate and inappropriate discharges, complications, and mortality. Sixty-three percent of implants were for primary prevention, 21.6% for secondary prevention, and 15.1% were replacements. The most common underlying condition was ischemic heart disease (66%), followed by dilated cardiomyopathy (23%).

Differences Between Autonomous Communities. Possible Reasons for Geographic Variation

The information in the registry reveals year after year that there are geographic differences in the availability of resources, indications for implantation, and the number of ICDs implanted in Spain. In 2008, the following 5 autonomous communities were above the national average for the number of implants reported to the registry: Navarre, the Canary Islands, Madrid, Castile and Leon, and Asturias.

There are many reasons for these regional differences, and for the national differences mentioned earlier, and not all of them are well understood.19 One of the characteristics that is common to countries with higher rates of ICD placement is the high number of implanting hospitals, as in the case of Germany and Italy.14 This may facilitate greater access to treatment and a greater ability to deal with the service overload created by increasing numbers of implants being performed. In Spain, in 2007 and 2008 there was a trend towards a weak correlation between the number of implanting hospitals per million population and the number of implants per million population in the different autonomous communities, highlighting the influence of health care availability on the variation in the use of cardiovascular technology.

Another possible explanation is a difference in the adherence to clinical practice guidelines or differences in their recommendations. The latter situation is apparent in the United Kingdom, where the indications for ICD placement provided in the guidelines of the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence,20 especially in relation to primary prevention, are more restrictive than those found in clinical practice guidelines from the American societies and the European Society of Cardiology. Other explanations for this variability include differences in the clinical presentation of the patients and in the prevalence of cardiovascular diseases, or in the economic restrictions associated with ICD placement.

A study has recently been published describing variations in the ICD implants performed in patients with heart failure in different hospitals in the United States and the factors associated with adherence to guidelines on ICD placement.21 ICDs were implanted in 20% of patients, but there was wide unexplained variation between hospitals (between tertiles of 1% and 35%). The hospitals with the highest numbers of ICD implants had more rapidly adopted other new evidence-based therapies for heart failure. They performed a greater number of percutaneous and surgical coronary revascularization procedures, had facilities for heart transplant, a greater number of hospital beds, and reported more extensive use of beta blockers and aldosterone antagonists. In the Spanish registry there was a correlation between higher numbers of implants and a higher percentage of implants for primary prevention.

Limitations

The number of implants reported to the registry constitutes almost 85% of the implants performed in Spain, according to data provided by the device manufacturers. That figure is lower than the 90% achieved in 2007, although it can be considered reasonably representative of the true situation in Spain. In addition, the information on the variables included in the data collection form was complete to a lesser extent than in previous years, particularly in the fields that generally receive the lowest number of responses. Both observations should be kept in mind when interpreting results from the registry, especially in relation to the differences in the number of implants performed between the different autonomous communities, since as in previous years the proportion of implants reported by some hospitals performing a large number of implants has been low. Nevertheless, the number of hospitals in which this was the case remains low.

The use of ICD placement for primary prevention in patients with ischemic heart disease and dilated cardiomyopathy, as in previous years, has not been detailed according to indication (MADIT II, SCDHeF, COMPANION, etc), given that not all the information necessary for such a subdivision is available.

Finally, the complications reported only correspond to those occurring during the procedure itself, and those that may occur or be detected shortly afterwards, such as heart failure, hematomas, electrode displacements, and many instances of pneumothorax, are not included.

Future Perspectives for the Spanish ICD Registry

The slight reduction in the number of implants reported and the lower quality of the information received (number of fields completed) is worthy of some consideration. Despite having eliminated the retrospective reporting of data, a slight reduction was observed in the proportion of completed fields for each category in the data collection form. Both factors, along with the reduction in the reporting of data from major implanting hospitals in Spain, may reveal a certain degree of fatigue associated with a voluntary registry that is maintained as a result of significant effort on the part of many individuals, including not only healthcare professionals but also staff from the ICD manufacturers and members of SEC, who are central to this endeavor.

It may now be time to consider changes in the registry to allow direct completion of web-based forms along with direct access to and analysis of data. It would also be very useful to include some basic but nevertheless relevant information for an ongoing evaluation of the results, such as mortality, device discharges during follow-up, and complications. This has been shown to be possible in some registries, such as the Ontario registry,18 and it has recently been employed, although only partially, in the United States13 and United Kingdom22 registries. In Spain, given the legal obligation to report implants, efforts should be made to reach agreements between health authorities, professionals, industry, and SEC to attempt to comply with current legislation and to professionalize and improve the quality of the registry, since the information it collects is important not only for health authorities but also for the implanting hospitals themselves.18,23

CONCLUSIONS

The 2008 Spanish ICD Registry recorded 84.7% of the ICD implants performed in Spain, and although this figure is slightly lower than in 2007, the registry continues to be representative of the number of procedures and indications for ICD placement employed in Spain. The number of implants reported to the registry has continued to increase, now reaching 76 implants per million population. The proportion of ICD implants performed for primary prevention has increased significantly and now represents 57% of all first implants. As in previous years, the number of implants in Spain continues to be clearly below the mean of more developed countries within the European Union and there continue to be marked differences in the implants reported among the different autonomous communities.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to all of the health care professionals involved in performing ICD implants in Spain who have voluntarily and unselfishly reported data to the registry.

We also thank the individuals from the ICD manufacturers (Medtronic, Boston Scientific, St. Jude Medical, Biotronik, and Sorin Group) for their collaboration in data collection and for returning data collection forms to SEC in the majority of implants carried out.

Finally, we thank SEC for the invaluable work done to input data and maintain the registry database; in particular we are grateful to Gonzalo Justes and José María Naranjo.

ABBREVIATIONS

CRT: cardiac resynchronization therapy

ICD: implantable cardioverter-defibrillator

LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction

NYHA: New York Heart Association

SCD: sudden cardiac death

SMVT: sustained monomorphic ventricular tachycardia

WG-ICD: working group on implantable cardioverter-defibrillators

Correspondence: Dr. R. Peinado Peinado. Sección de Arritmias. Servicio de Cardiología. Hospital Universitario La Paz.

P.o de la Castellana, 261. 28046 Madrid. España.

E-mail: rpeinado@secardiologia.es