Keywords

INTRODUCTION

This article is the customary annual update analysis describing results of heart transplantation carried out in Spain between the first such procedure, performed in May 1984, and December 31, 2007.1-18

The registry includes all heart transplants performed by all teams at all centers in Spain and is therefore an accurate account of the status of heart transplantation in the country. The report's reliability is founded on the nationwide use of a similar database constructed on mutually agreed principles, which standardizes variables and unifies possible responses.

METHODS

Patients and Centers

Nineteen heart transplantation centers supplied the registry with data (Table 1) although only 17 actively performed transplants in 2007.

TABLE 1. Spanish Registry on Heart Transplantation, 1984-2007. Centers Reporting

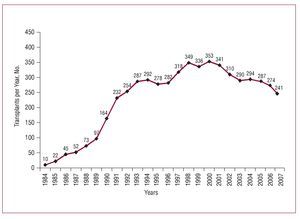

In the 23 years that heart transplantation procedures have been being performed in Spain, the total number of operations has reached 5482. Figure 1 presents the distribution of the number of heart transplants per year. Of these, 94% were isolated orthotopic transplants. Table 2 shows the distribution of transplants by procedure type.

Figure 1. Number of heart transplants per year. Spanish Registry on Heart Transplantation 1984-2007.

Design

The year 2007 has seen the creation of a new database using Access software and the inclusion of as many as 175 clinical variables. The database includes data on recipients, donors, surgery, immunosuppression, and follow-up. Each center sends data to the person responsible for the registry who collates and sends them to the independent statistics company for analysis. This same company is responsible for external monitoring of the data to guarantee their reliability.

This year, we have also sent the registry to the Committee for Clinical Research Ethics of the Hospital Universitario La Fe, Valencia, for approval. At the time of writing, we are in the process of submitting the registry to the Spanish Ministry of Health and Consumer Affairs to guarantee fulfillment of Spanish Data Protection Law 15/1999.

Statistical Analysis

Variables are presented as mean (SD). Data on survival are analyzed in Kaplan-Meier curves and compared using the log rank test. A P value less than .05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Heart Transplant Recipient Profile

In Spain, the profile of the average heart transplant recipient is that of a 52-year-old man diagnosed with ischemic heart disease or idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy and with blood group A or O. Table 3 shows the clinical profile of isolated heart transplant (HT) recipients by age-group; retransplantation recipients appear in a separate column.

Waiting List Mortality and Days-to-Transplant

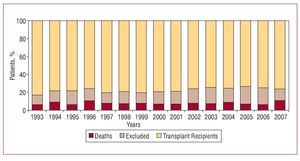

In 2007, waiting list mortality was 10%. The percentage of patients excluded from transplant after inclusion on the waiting list was 18%. Figure 2 shows the annual percentage of waiting list patients who received a transplant, were removed from the list without receiving one, or died before receiving one.

Figure 2. Patient outcomes following inclusion on the heart transplantation waiting list. Spanish Registry on Heart Transplantation 1984-2007.

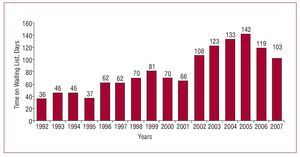

In recent years, mean waiting list time for recipients prior to undergoing HT has been 122 days. Figure 3 shows how this has evolved over the last 16 years.

Figure 3. Year-on-year evolution of mean waiting list to heart transplantation days. Spanish Registry on Heart Transplantation 1984-2007.

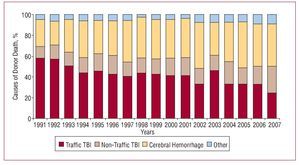

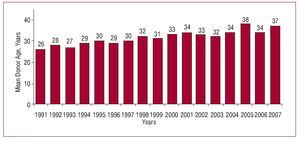

Cause of Death and Mean Donor Age

Most heart transplant donors die of traumatic brain injury. In recent years, mean donor age has been 35 years (Figures 4 and 5).

Figure 4. Year-on-year evolution of causes of heart transplant donor deaths. Spanish Registry on Heart Transplantation 1984-2007. TBI indicates traumatic brain injury.

Figure 5. Year-on-year evolution of mean age of heart transplant donors. Spanish Registry on Heart Transplantation 1984-2007.

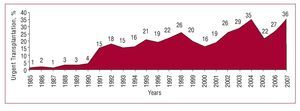

Urgent Transplantation

In 2007, the rate of indications for urgent transplantation was 36%. This was greater than that of recent years (27%). Figure 6 shows the evolution of indications for urgent HT over the years.

Figure 6. Year-on-year evolution of urgent heart transplantations. Spanish Registry on Heart Transplantation 1984-2007.

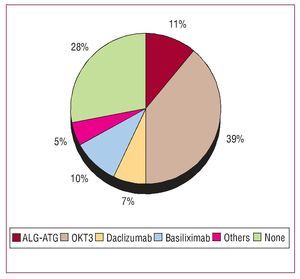

Immunosupression

In Spain, most HT recipients (72%) received induced immunosuppression treatment. The drugs used appear in Figure 7.

Figure 7. Induced immunosuppression. Drugs administered. Spanish Registry on Heart Transplantation 1984-2007.

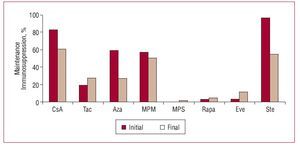

Maintenance immunosuppression treatment administered and changes made during transplant patients' clinical course are shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8. Maintenance immunosuppression. Variations in clinical course by drug type. Spanish Registry on Heart Transplantation 1984-2007. Aza indicates azathioprine; CyA, cyclosporine A; Eve, everolimus; MPM, mycophenolate mofetil; MPS, mycophenolate sodium; Rapa, rapamycin; Ste, steroids; Tac, tacrolimus.

Survival

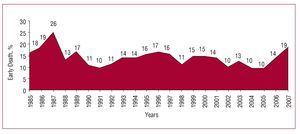

Early mortality (death at the first 30 days post-transplantation) was 19% in 2007. This was greater than the figure for recent years (12%) as Figure 9 shows.

Figure 9. Year on year percentage evolution of early deaths (at the first 30 days). Spanish Registry on Heart Transplantation 1984-2007.

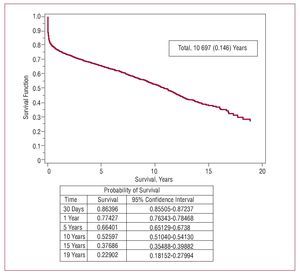

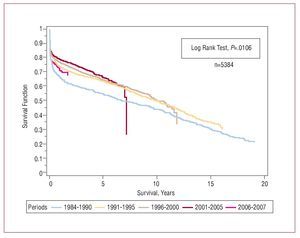

When survival rate data for 2007 were added to those of previous years, we obtained 86% 1-month actuarial survival, and 1-, 5-, 10-, and 15-year rates of 78%, 67%, 53%, and 38%, respectively. Average recipient survival for the entire series was 10.7 years (Figure 10). Survival by periods showed better results in the last stage with 1- and 5-year survival rates of 80% and 75%, respectively, and significant differences between periods (Figure 11).

Figure 10. Actuarial survival curve (Kaplan-Meier) for the entire series. Spanish Registry on Heart Transplantation 1984-2007.

Figure 11. Survival curve by periods. Spanish Registry on Heart Transplantation 1984-2007.

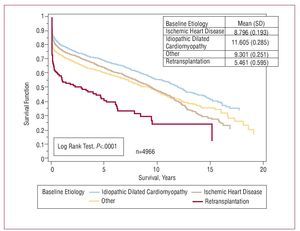

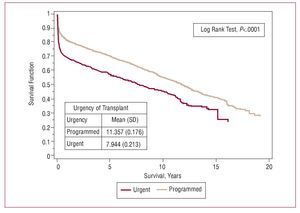

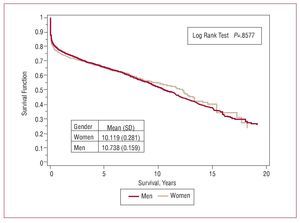

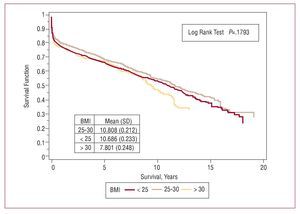

We made univariate comparisons of some variables and found significant differences between HT recipients according to baseline etiology, degree of urgency and age at transplantation (Figures 12-14). We found no differences for gender or body mass index (Figures 15 and 16).

Figure 12. Survival curves according to etiology indicating transplantation. Spanish Registry on Heart Transplantation 1984-2007.

Figure 13. Survival curves by degree of urgency. Spanish Registry on Heart Transplantation 1984-2007.

Figure 14. Survival curves by recipient age. Spanish Registry on Heart Transplantation 1984-2007.

Figure 15. Survival curves by gender. Spanish Registry on Heart Transplantation 1984-2007.

Figure 16. Survival curves by body mass index (BMI). Spanish Registry on Heart Transplantation 1984-2007.

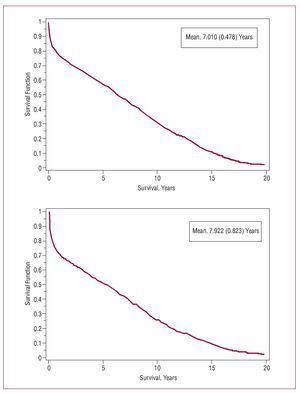

Figure 17 shows rejection- and infection-free survival data.

Figure 17. Rejection-free (above) and infection-free (below) survival. Spanish Registry on Heart Transplantation 1984-2007.

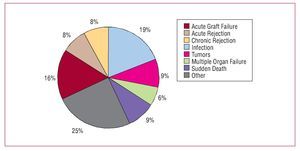

Causes of Death

The most frequent cause of death in the entire series was infection (19%) followed by combined graft vascular disease and sudden death (17%), acute graft failure (16%), tumors (9%), and acute rejection (8%) (Figure 15).

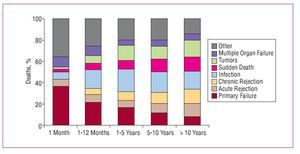

When causes of mortality are analyzed by periods, differences can be seen at the first 30 days (acute graft failure), 1-12 months (infections), and >1 year (tumors and the combination of sudden death with chronic rejection and infection). Figure 19 shows the distribution of causes of death by periods.

Figure 18. Causes of death. Spanish Registry on Heart Transplantation 1984-2007.

Figure 19. Causes of death by periods. Spanish Registry on Heart Transplantation 1984-2007.

DISCUSSION

With 23 years' experience of HT in Spain, and nearly 5500 transplants performed, we would say that this procedure can be offered to the whole population with the certainty that levels of knowledge, control and survival are similar to those of other countries in western Europe and around the world. Analysis of the Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation annual report demonstrates this.19,21

An important advantage of our registry is that it is compiled from a standardized database that only permits a previously agreed range of responses. All teams update results annually and submit figures to the registry coordinator who collates the data and sends them to an independent statistics consultancy for analysis. We believe this method greatly enhances the reliability of our results and avoids errors of the kind so often found in nonstandardized databases. In 2007, we increased the number of variables analyzed for each patient to 175. Furthermore, we sent the registry to a hospital ethics committee and to the Spanish Ministry of Health and

Consumer Affairs to give it legal coverage and ensure adequate protection of patient healthcare data. To attain improved quality and greater data reliability, we contracted an independent external auditor to conduct a study in all transplant centers in order to guarantee data validity to the utmost.

Fortunately, in 2007, the number of active transplantation centers did not vary. Any increase would have worried the majority of the transplant teams because the number of optimal donors has shown a clear tendency to fall whereas the ratio between the number of centers and the number of transplants has increased. The fact that fewer transplant procedures are being performed leads to the under use of resources in hospitals equipped to conduct a great number of transplants, and to a longer learning process needed to achieve adequate results. The only tangible benefit for patients is the convenience of being able to undergo transplantation without having to travel far from home.

In 2007, total transplants performed fell once more (from 274 to 241): 33 fewer than in 2006. This may be purely by chance, but the evident trend towards the performance of fewer transplants is worrying. In fact, since 2000 when 353 transplants were conducted, a gradual though irregular fall has been the trend. There is no single explanation for the reduction in the number of donors, but it seems clear that incidence of death from traumatic brain injury has decreased while care of patients with multiple trauma in specialized units has improved. The scarcity of ideal donors has caused an increase in days waiting to obtain an optimal organ despite the use of older donors. Consequently, death while on the waiting list has increased (10%) although here we should add those patients removed from the list due to severe decompensations and not included again, and who die after their removal from the list. According to Spain's national transplant organization they account for some 9% of deaths.22 Consequently, mortality among patients waiting for a heart is 19%.

The clinical profile of patients has not changed in recent years. We analyzed HT recipients in 3 groups (pediatric, adult, and retransplantation) as each of these is indicated for transplant for very different reasons: pediatric patients are operated for congenital heart disease or idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy; they have slightly higher pulmonary resistances and do not present cardiovascular risk factors. In contrast, patients undergoing retransplantation are usually indicated for graft vascular disease; they present greater organ deterioration and more risk factors. This may be a more accurate explanation for the bad prognosis of these patients than the fact that they undergo a second transplant.

Urgent heart transplantation is somewhat controversial as these operations have specific characteristics (recipients in worse clinical condition, less-than-ideal donors, longer periods of ischemia) that entail a worse prognosis than programmed transplants. In 2007, the percentage of urgent transplants increased (36% in 2007 vs 27% in 2006). This figure is higher than the mean for the last 5 years (28%). The cause of these fluctuations in indication for urgent HT is not wholly clear; nor are the differences in geographical distribution. However, the low number of donors clearly increases the chances of urgent transplantation. Indication for urgent transplantation has been questioned given that it offers poorer results. However, the transplant teams are of the opinion that this option should continue to exist, in a controlled form, as it is the only therapeutic option available to the subgroup of patients with advanced heart failure and uncontrollable acute decompensation. In any event, we must remember that, as European guidelines on acute heart failure recommend, it is better to stabilize heart failure rather than indicate for urgent transplantation and HT should not be considered a treatment for unstable acute heart failure23 (among other things, because of the time taken in locating a donor even in cases as urgent as these).

Most transplant teams use induced immunosuppression (72%). The most frequent treatment is with OKT3 antilymphocyte antibodies (39%), although currently interleukin 2 antagonists are more commonly used, accounting for 17% of the total. The maintenance immunosuppressor treatment most frequently used is cyclosporine, azathioprine/mycophenolate mofetil, and steroids. However, depending on patient clinical course, the introduction of other drugs such as tacrolimus, rapamycin, or everolimus is common.

Incidence of early mortality increased in 2007 with respect to 2006 (19% vs 14%). This may be due to the worse profile of recipients, as well as increased donor age and longer times of ischemia motivated by the increase in urgent transplants. The early period is probably the most important in improving survival, as the survival curve stabilizes after the first months post-transplantation.

Over the years, overall survival has shown a clear trend towards progressive improvement. However, logically, the number of patients added to the Registry each year represents a comparatively smaller percentage of the total. Thus, chances of finding substantial changes in 1 year are very remote and analysis of survival by periods is more illuminating. In recent years, survival has improved significantly by comparison with earlier periods.

Indication for transplantation is clearly linked to survival. Patients diagnosed with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy have a higher survival rate than other

HT recipients because they are younger and present fewer cardiovascular risk factors.

The most frequent cause of death in the entire series is acute graft failure (25%), followed by infection (19%). However, cause of death is usually related to time post-transplantation. Thus, at the first month, the most frequent cause is acute graft failure; at 1-12 months, infection; and then the combination of sudden death and chronic rejection, infection, and tumors.

It is important to note that, especially in recent years, infection seems to be gaining ground as a cause of death, whereas death due to acute rejection is less frequent. This imbalance could be due to the over-administration of immunosuppressor drugs that prevent rejection but favor infection.

CONCLUSIONS

In recent years, the annual volume of heart transplantations has fallen. This has led to high waiting list mortality and the use of increasingly older donors.

In general, (early and late) survival rate figures are similar to those published in international registry reports and have improved year on year, especially in the last 5 years.

We should continue to try to reduce the high incidence of acute graft failure as this would have a particularly good effect on the probability of immediate post-operative and overall survival.

Given that infection is a more frequent cause of morbidity and mortality than rejection, we should pay it more attention and place it among the principle objectives of general studies and of clinical trials of drugs.

Statistical analysis conducted with unconditional financial support from Novartis Trasplante.

Correspondence: Dr. L. Almenar-Bonet.

Avda. Primado Reig, 189-37. 46020 Valencia. España.

E-mail: lu.almenarb5@comv.es

Received June 11, 2008.

Accepted for publication July 8, 2008.