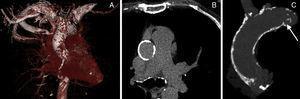

Thoracic aorta calcification is associated with coronary and valvular calcification and increased risk of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events.1 Porcelain aorta represents excessive calcification of the thoracic ascending aorta (Figure) and is a challenging substrate for cardiac surgeons because aortic cross-clamping and aortotomy may cause excessive aortic injury and/or release of thromboembolic material that may cause periprocedural stroke.2 Aortic valve replacement in patients with a porcelain aorta may mandate advanced surgical techniques including replacement of the ascending aorta under deep hypothermic circulatory arrest, endarterectomy, or balloon-assisted endovascular clamping to minimize manipulation of the heavily calcified aorta. The apicoaortic conduit is a technique to bypass an excessively calcified ascending thoracic aorta, but this technique can be hampered by concomitant aortic regurgitation and more generalized calcifications that complicate the distal anastomosis of the conduit.3 Transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) represents a highly attractive “no-touch” alternative for patients with severe aortic stenosis and porcelain aorta. The emergence of TAVI has revolutionized the treatment of aortic stenosis in patients at (very) high risk for operative mortality. In truly inoperable patients, TAVI is the only life-prolonging treatment option with a stunning 25% absolute reduction in 2-year mortality compared with medical therapy and balloon valvuloplasty.4 Based on the favorable PARTNER (Placement of Aortic Transcatheter Valves) Cohort A and B data, the recently updated European Society of Cardiology and the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery guidelines on the management of valvular heart disease strongly recommend TAVI as the treatment option of choice in inoperable aortic stenosis patients with a reasonable life expectancy and suggest that TAVI is a reasonable alternative to surgical aortic valve replacement in aortic stenosis patients at high operative risk.5,6 With the expanding treatment armamentarium, meticulous risk stratification is clearly essential to select the best treatment modality for each patient with aortic stenosis. The Society of Thoracic Surgeons and the logistic EuroSCORE were validated and calibrated in relatively large surgical databases but tend to lose accuracy in the higher risk cohorts.7 Not surprisingly, these established surgical risk models perform poorly in the contemporary TAVI patient population, which consists of older persons who often have multiple comorbidities. Furthermore, particular risk variables have emerged, such as frailty, chest deformity, and porcelain aorta that are not considered in the above-mentioned models.

In an article published in Revista Española de Cardiología, Pascual et al.8 report on the short- and longer-term outcomes after TAVI with the Medtronic CoreValve System in patients with porcelain aorta. A total of 449 patients were included from 3 academic institutions. The prevalence of porcelain aorta was 8.0%. Bearing in mind the nonuniformity in the definitions used, atherosclerosis of the aorta is reported in up to one-third of octogenarians undergoing cardiac surgery and true porcelain aorta in 1% to 5%.9–11 The incidence of porcelain aorta in large national TAVI registries varies, being 5% in the FRANCE-2 Registry and 11% in a German Registry.12–14

In the studied patient population with porcelain aorta, the prevalence of typical risk factors for atherosclerotic disease, a history of peripheral arterial disease, and coronary revascularization was high. The overall calculated logistic EuroSCORE was no different from that in patients without porcelain aorta. Consequently, the patient cohort with porcelain aorta may in reality have been at even higher operative risk, given that porcelain aorta per se is not considered in the logistic EuroSCORE. It would have been interesting to know how many patients with porcelain aorta had a low calculated logistic EuroSCORE, yet were still considered to be at high operative risk. Moreover, one may wonder whether porcelain aorta per se indicates high operative risk, regardless of the presence of significant comorbidities, and whether it might only impact procedural outcome rather than long-term outcome. In this regard, it is striking that porcelain aorta per se did not impose insurmountable procedural/technical hurdles to these TAVI-experienced heart teams. Of note, proportionally more patients in the porcelain aorta cohort were treated using the axillary/subclavian access route. Since a “transfemoral-first” strategy was applied, this illustrates that porcelain aorta was associated with less favorable iliofemoral trajectories due to small size, tortuosity, calcification and/or atherosclerotic disease. The primary endpoint of all-cause mortality at 2 years did not differ between patients with or without porcelain aorta.

Porcelain aorta is a generic entity with generalized and circumferential calcification of the thoracic ascending aorta and thus needs to be considered separately from other risk variables or comorbidities. It is typically characterized by excessive calcium in the aortic wall, which can be–but is not exclusively–associated with adluminal atherosclerotic plaque. Aortic calcification can be located within the tunica intima, eccentric, and initiated at the base of necrotic fibrofatty plaques (atherosclerotic type) or can be located within the tunica media (nonatherosclerotic). This is an important nuance, because the absence of protruding atherosclerosis excludes a significant source for cerebral embolization. The finding that TAVI with porcelain aorta was not associated with an increased stroke rate in the study of Pascual et al.8 may indeed suggest that porcelain aorta and protruding atheromatosis are not interrelated. Therefore, alternative access strategies do not seem to have a particular advantage over the (routine) transfemoral route in patients with porcelain aorta provided the iliofemoral arterial tree is accessible.

Porcelain aorta does not necessarily share the exact same pathophysiological mechanisms with atherosclerosis. It can appear in distinct phenotypes with different underlying mechanisms. Basic concepts in aging, radiation, and chronic kidney disease may illustrate the following: a) Aging evokes paracrine osteogenic signals that are regulated by fibrofatty expansion via apoptotic vesicles arising from dead and dying vascular smooth muscle cells. This process promotes aortic calcium deposition, inducing specific changes in the vessel wall of larger arteries, including collagen and calcium deposition and loss of elastic fibers in the medial layer, causing stiffening of the arterial tree;15b) Mediastinal radiation may cause aortitis, which generates calcium salt deposits as a sequel of scarred intima or media,16 and c) Patients with chronic kidney disease demonstrate not only accelerated atherosclerosis but also diffuse calcification of the media of large arteries (so called Monckeberg sclerosis). Excessive media calcification is the result of osteoblastic transformation of vascular smooth muscle cells, which leads to the formation of hydroxyapatite in a milieu of excessive calcium and phosphate.17

So far, there is no uniformly accepted definition of porcelain aorta. In the study by Pascual et al.8 the diagnosis of porcelain aorta was established when 2 cardiac surgeons agreed that the patient was not a suitable candidate for surgical aortic valve replacement based on the identification of unfavorable aortic calcification with computed tomography scan or conventional invasive angiography. Clearly, the absence of computed tomography information in all patients is a limitation to this study and may lead to under- or overreporting of its actual prevalence. This is further underscored by the fact that 2 patients in the study eventually crossed over from surgical aortic valve replacement to TAVI because the porcelain aorta was only identified after sternotomy. The Valve Academic Research Consortium is an international collaboration of representatives from clinical research organizations, academic institutions and competent authorities that has recently issued its second consensus document on TAVI endpoint definitions.18 This document defines porcelain aorta as “heavy circumferential calcification or severe atheromatous plaques of the entire ascending aorta extending to the arch such that aortic cross-clamping is not feasible”. Furthermore, the Valve Academic Research Consortium proposes noncontrast axial computed tomography scan as the imaging tool of first choice to assess calcification at the level of the sinotubular junction, ascending thoracic aorta, innominate artery, and transverse arch. In this spirit, all patients who are eligible for the currently ongoing trials randomizing to surgical aortic valve replacement or TAVI undergo multislice computed tomography scan to assess the aorta and the peripheral arterial vasculature. Incorporation of multislice computed tomography and this uniform definition in a routine work-up for all patients may further elucidate the true frequency and implications of porcelain aorta.

Not all calcifications in the thoracic aorta are equally important or are likely to impair aortic cross-clamping. The Leipzig Heart Center has proposed a refined classification of porcelain aorta based on the extent and localization of the calcium in the thoracic aorta, which could serve as a uniform guide during the (local) heart team discussion among cardiac surgeons, cardiologists, imaging specialists, and anesthesiologists.19 Furthermore, Bapat et al.20 evaluated a series of calcified ascending aortas and reported that, in the majority of patients, the upper outer quadrant of the distal ascending aorta, the so called transaortic access zone, remained accessible to instrumentation and a direct aortic (or transaortic) TAVI approach, clearly putting the issue of porcelain aorta in a different perspective. Not all porcelain aortas should not be touched.

With improved overall life expectancies and as a result of the aging of Western societies, one can expect an epidemic of patients with calcified degenerative aortic valve disease and concomitant porcelain aorta in the near future. The study by Pascual et al.8 demonstrates that porcelain aorta does not affect procedural outcome with TAVI unlike its significant technical implications for surgical aortic valve replacement. A logical conclusion is that TAVI is becoming the standard of care for patients with aortic stenosis and porcelain aorta.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTNone declared.