In acute myocardial infarction (MI), novel highly deliverable drug-eluting stents (DES) may be particularly valuable as their flexible stent designs might reduce device-induced traumas to culprit lesions. The aim of the study was to assess the safety and efficacy of percutaneous coronary interventions with 2 novel durable polymer-coated DES in patients with acute MI.

MethodsThe prospective, randomized DUTCH PEERS (TWENTE II) multicenter trial compares Resolute Integrity and Promus Element stents in 1811 all-comer patients, of whom 817 (45.1%) were treated for ST-segment elevation MI or non—ST-segment elevation MI and the 2-year outcome is available in 99.9%. The primary clinical endpoint is target vessel failure (TVF), a composite of cardiac death, target vessel related MI, or target vessel revascularization.

ResultsOf all 817 patients treated for acute MI, 421 (51.5%) were treated with Resolute Integrity and 396 (48.5%) with Promus Element stents. At the 2-year follow-up, the rates of TVF (7.4% vs 6.1%; P = .45), target lesion revascularization (3.1% vs 2.8%; P = .79), and definite stent thrombosis (1.0% vs 0.5%; P = .69) were low for both stent groups. Consistent with these findings in all patients with acute MI, outcomes for the 2 DES were favorable and similar in both, with 370 patients with ST-segment elevation MI (TVF, 5.1% vs 4.9%; P = .81) and 447 patients with non—ST-segment elevation MI (TVF, 9.0% vs 7.5%; P = .56).

ConclusionsResolute Integrity and Promus Element stents were both safe and efficacious in treating patients with acute MI. The present 2-year follow-up data underline the safety of using these devices in this particular clinical setting.

Keywords

Early-generation drug-eluting stents (DES) were associated with an increased risk of late and very late stent thrombosis, which was particularly high after percutaneous coronary interventions (PCI) for acute myocardial infarction (MI), compared with bare metal stents.1–5 New-generation DES (also known as second-generation DES) have more biocompatible durable polymer-based coatings and showed more favorable safety profiles in broad patient populations6–13 and in patients with high-risk acute coronary syndromes, such as ST-segment elevation MI (STEMI) and non—ST-segment elevation MI (NSTEMI).14–19

At present, there is a widespread use of novel durable polymer DES that use the established drug-plus-polymer combinations of the initial new-generation DES on new stent platforms that have undergone substantial changes in design and/or material compared with their second-generation counterparts.12,20 In patients with acute MI, these novel, flexible stent designs may be particularly valuable, as their increased conformability to the vessel anatomy might reduce both the device-induced trauma to the frequently already disrupted culprit lesion and the likelihood of incomplete stent apposition—a major risk factor of stent thrombosis.21 Nevertheless, there are scarce data on the safety and efficacy of these DES in patients with acute MI.

The Resolute Integrity (Medtronic; Santa Rosa, California, United States) and Promus Element stents (Boston Scientific; Natick, Massachusetts, United States), which are novel, durable polymer-coated new-generation DES, have so far only been compared in the randomized, multicenter DUTCH PEERS trial, which enrolled all-comer patients, of whom a very large proportion had had an acute MI.20 In the present substudy, we assessed the 2-year safety and efficacy of Resolute Integrity and Promus Element stents in treating patients undergoing PCI for acute MI.

METHODSStudy Design and Patient PopulationIn the present substudy of the randomized, patient-blinded, multicenter DUTCH PEERS (TWENTE II) all-comer trial (ClinicalTrials.govNCT01331707),20 we analyzed post-hoc the data of all patients who presented with acute MI at the time of enrolment. The study design and procedures of the investigator-initiated DUTCH PEERS trial have previously been described in detail20 and the 2-year clinical outcome has been reported.22 In brief, between November 25, 2010 and May 24, 2012, DUTCH PEERS enrolled a total of 1811 all-comer patients who underwent PCI procedures for de-novo and re-stenotic lesions in coronary arteries or bypass grafts. There was no limit for lesion length, reference size, or the number of lesions or diseased vessels to be treated. The trial complied with the Declaration of Helsinki for investigation in humans and was approved by the accredited Medical Ethics Committee Twente and the institutional review boards of all participating centers. All patients provided written informed consent.

Coronary Intervention and Implanted StentsInterventional procedures were performed according to standard techniques and routine clinical protocols. Treatment of all target lesions within a single PCI procedure was encouraged, except for patients with STEMI. Staged procedures with allocated DES were permitted within 6 weeks. Lesion predilation, manual thrombus aspiration, use of glycoprotein IIb-IIIa receptor antagonists, direct stenting, and stent postdilation were left at the operator's discretion. Anticoagulation during PCI was generally achieved with unfractionated heparin (> 99%). Dual antiplatelet therapy, which generally consisted of aspirin and clopidogrel (> 99%), was usually prescribed for 12 months.

Prior to stent implantation, patients were randomly (1:1) assigned to treatment with 1 of the 2 study stents: the Resolute Integrity zotarolimus-eluting stent releases zotarolimus from the 6μm BioLynx conformal, permanent polymer system (blend of 3 polymers), which has been highly effective on Resolute stents (Medtronic)8,9 and uses the sinusoid-shaped single cobalt-chromium wire-based, open-cell design Integrity stent platform (91μm round struts)20; the Promus Element everolimus-eluting stent releases everolimus from a 7-μm conformal, permanent fluoropolymer coating, which recently demonstrated its efficacy in other patient populations6–9,23 and uses the laser-cut, platinum-chromium alloy (highly radiopaque), open-cell design (serpentine rings connected by links) Element stent platform (81μm struts).20,24

Coronary Angiographic AnalysisAngiographic analysts from the Thoraxcentrum Twente, blinded to clinical outcome, performed a central analysis of the angiography runs of all trial participants according to current standards. The analyses were executed by use of the software QAngio XA (version 7.2, Medis; Leiden, The Netherlands).20

Assessment of Clinical Follow-up and Adjudication of Clinical EventThe follow-up procedures have previously been reported.20,22 In brief, systematic laboratory and electrocardiographic testing was performed. Research nurses and analysts, blinded to the treatment arm, obtained information on clinical endpoints by use of a medical records and a medical questionnaire or, in the absence of a response, a telephone follow-up that was based on the same questions.

Monitoring was performed by the independent Contract Research Organization (CRO) Diagram (Zwolle, The Netherlands), as previously described.20 Processing of clinical outcome data and event adjudication by an independent clinical event committee were performed by the CRO Cardialysis (Rotterdam, The Netherlands). An accredited ethics committee monitored the safety data.

Definition of Clinical EndpointsThe definition of clinical endpoints, which have previously been described in detail,9,20 followed suggestions from the Academic Research Consortium.25,26 In brief, target vessel failure (TVF), the primary endpoint, was defined as a composite of cardiac death, target vessel-related MI, or clinically indicated target vessel revascularization. Death was considered cardiac, unless an unequivocal noncardiac cause could be established. A target vessel-related MI was related to the target vessel or could not be related to another vessel. Target vessel revascularization and target lesion revascularization were considered clinically indicated if the angiographic diameter stenosis was ≥ 70%, or ≥ 50% in the presence of ischemic signs or symptoms. Stent thrombosis was classified according to the Academic Research Consortium definitions.25,26 The composite clinical endpoint target lesion failure was defined as cardiac death, target vessel-related MI, or clinically indicated target lesion revascularization).

Statistical AnalysisContinuous variables are expressed as mean ± standard deviation, and categorical data are presented as numbers and percentages. Differences between dichotomous and categorical variables were assessed with the chi-square or Fisher exact tests, while continuous variables were assessed with the student t test. The Kaplan-Meier analysis was used to calculate the time to clinical endpoints and the log rank test was applied to compare between-group differences. We performed an additional analysis of the data for the primary endpoint using restricted mean survival time (RMST).27 Cox regression was used to adjust for imbalances in the 2 groups. All P-values and confidence intervals were 2-sided and a P-value < .05 was considered significant. Data analysis was performed using SPSS version 17 (SPSS Inc.; Chicago, Illinois, United States) and STAT/MP version 14.0 (StataCorp LP: College Station, Texas, United States).

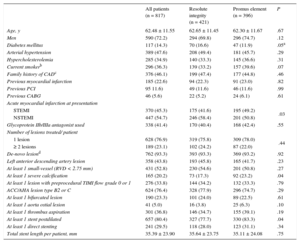

RESULTSCharacteristics of Patients, Lesions, and Interventional ProceduresOf all DUTCH PEERS trial participants, 817 presented with acute MI and were assessed in the present study. A total of 421 (51.5%) patients were allocated to treatment with Resolute Integrity stents and 396 (48.5%) to treatment with Promus Element stents; 370 (45.3%) patients presented with STEMI, treated by primary PCI (no rescue PCI), while 447 (54.7%) patients had NSTEMI. Of all patients with NSTEMI, 72 (16.1%) presented with nonpatent culprit vessels, and 132 (29.5%) had impaired coronary flow. In patients who initially presented with a STEMI, the rate of direct stenting was higher than in patients with NSTEMI at presentation (36.2% vs 29.5%; P < .001). The baseline characteristics of patients and lesions, and procedural data were similar for both stent groups (Table 1); nevertheless, patients in the Resolute Integrity stent group more often presented with NSTEMI (58.4% vs 50.8%; P = .03), and target lesions of this group were less often severely calcified (17.3% vs 23.2%; P = .04) and were less often postdilated (77.7% vs 83.3%; P = .04). There was no significant difference in any other procedure-related parameter (Table 1).

Characteristics of Patients, Target Lesions, and Interventional Procedures

| All patients (n = 817) | Resolute integrity (n = 421) | Promus element (n = 396) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 62.48 ± 11.55 | 62.65 ± 11.45 | 62.30 ± 11.67 | .67 |

| Men | 590 (72.2) | 294 (69.8) | 296 (74.7) | .12 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 117 (14.3) | 70 (16.6) | 47 (11.9) | .05a |

| Arterial hypertension | 389 (47.6) | 208 (49.4) | 181 (45.7) | .29 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 285 (34.9) | 140 (33.3) | 145 (36.6) | .31 |

| Current smokerb | 296 (36.3) | 139 (33.2) | 157 (39.6) | .07 |

| Family history of CADc | 376 (46.1) | 199 (47.4) | 177 (44.8) | .46 |

| Previous myocardial infarction | 185 (22.6) | 94 (22.3) | 91 (23.0) | .82 |

| Previous PCI | 95 11.6) | 49 (11.6) | 46 (11.6) | .99 |

| Previous CABG | 46 (5.6) | 22 (5.2) | 24 (6.1) | .61 |

| Acute myocardial infarction at presentation | ||||

| STEMI | 370 (45.3) | 175 (41.6) | 195 (49.2) | .03 |

| NSTEMI | 447 (54.7) | 246 (58.4) | 201 (50.8) | |

| Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa antagonist used | 338 (41.4) | 170 (40.4) | 168 (42.4) | .55 |

| Number of lesions treated/ patient | ||||

| 1 lesion | 628 (76.9) | 319 (75.8) | 309 (78.0) | .44 |

| ≥ 2 lesions | 189 (23.1) | 102 (24.2) | 87 (22.0) | |

| De-novo lesiond | 762 (93.3) | 393 (93.3) | 369 (93.2) | .92 |

| Left anterior descending artery lesion | 358 (43.8) | 193 (45.8) | 165 (41.7) | .23 |

| At least 1 small-vessel (RVD < 2.75 mm) | 431 (52.8) | 230 (54.6) | 201 (50.8) | .27 |

| At least 1 severe calcification | 165 (20.2) | 73 (17.3) | 92 (23.2) | .04 |

| At least 1 lesion with preprocedural TIMI flow grade 0 or 1 | 276 (33.8) | 144 (34.2) | 132 (33.3) | .79 |

| ACC/AHA lesion type B2 or C | 624 (76.4) | 328 (77.9) | 296 (74.7) | .29 |

| At least 1 bifurcated lesion | 190 (23.3) | 101 (24.0) | 89 (22.5) | .61 |

| At least 1 aorta ostial lesion | 41 (5.0) | 16 (3.8) | 25 (6.3) | .10 |

| At least 1 thrombus aspiration | 301 (36.8) | 146 (34.7) | 155 (39.1) | .19 |

| At least 1 stent postdilated | 657 (80.4) | 327 (77.7) | 330 (83.3) | .04 |

| At least 1 direct stenting | 241 (29.5) | 118 (28.0) | 123 (31.1) | .34 |

| Total stent length per patient, mm | 35.39 ± 23.90 | 35.64 ± 23.75 | 35.11 ± 24.08 | .75 |

ACC/AHA, American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association; CAD, coronary artery disease; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; CTO, chronic total occlusion; NSTEMI, non—ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; RVD, reference vessel diameter; STEMI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; TIMI, Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction.

Data are expressed as n (%) or mean ± standard deviation.

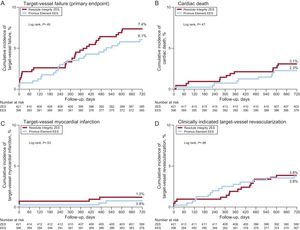

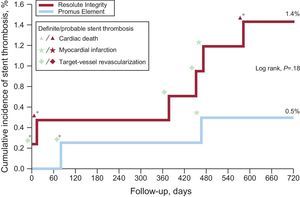

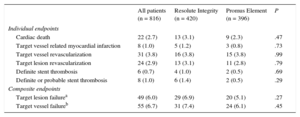

One patient in the Resolute Integrity stent group withdrew consent, but 2-year follow-up data were obtained for all remaining 816 patients (99.9%). Table 2 presents the various individual and composite clinical outcome parameters, comparing the DES groups. Time-to event analysis of the primary clinical endpoint TVF (7.4% vs 6.1%; P = .45) revealed no significant difference between stent groups (Figure 1). The estimated RMST up to 720 days for patients in the Resolute Integrity stent group was 686.1 days and was 694.4 days for patients in the Promus Element stent group. The estimated difference of the 2 RMST (ie, of Promus Element minus Resolute Integrity) was 8.3 days (95%CI: −8.7 to 25.3; P = .34). The different components revealed no differences either, and the definite stent thrombosis rate at the 2-year follow-up was low for both stent groups (1.0% vs 0.5%; P = .69; Table 2, and Figure 2). Adjustment for age, sex, diabetes mellitus, smoking, and stent postdilatation did not change the results.

Two-year Clinical Outcome of All Patients Treated for Acute Myocardial Infarction and for Allocated Stent Groups

| All patients (n = 816) | Resolute Integrity (n = 420) | Promus Element (n = 396) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual endpoints | ||||

| Cardiac death | 22 (2.7) | 13 (3.1) | 9 (2.3) | .47 |

| Target vessel related myocardial infarction | 8 (1.0) | 5 (1.2) | 3 (0.8) | .73 |

| Target vessel revascularization | 31 (3.8) | 16 (3.8) | 15 (3.8) | .99 |

| Target lesion revascularization | 24 (2.9) | 13 (3.1) | 11 (2.8) | .79 |

| Definite stent thrombosis | 6 (0.7) | 4 (1.0) | 2 (0.5) | .69 |

| Definite or probable stent thrombosis | 8 (1.0) | 6 (1.4) | 2 (0.5) | .29 |

| Composite endpoints | ||||

| Target lesion failurea | 49 (6.0) | 29 (6.9) | 20 (5.1) | .27 |

| Target vessel failureb | 55 (6.7) | 31 (7.4) | 24 (6.1) | .45 |

Revascularizations were clinically indicated.

Data are expressed as No. (%).

Kaplan-Meier curves for the primary composite endpoint of target vessel failure and its individual components. The time-to-event curves are displayed for patients in the DUTCH PEERS trial, who were initially treated for myocardial infarction. EES, everolimus-eluting stent; ZES, zotarolimus-eluting stent.

Cumulative incidence of definite-or-probable stent thrombosis in drug-eluting stent groups and associated adverse cardiovascular events. In the periprocedural phase (ie, the first 48hours), there was only 1 definite stent thrombosis in a patient in the Resolute Integrity arm while on DAPT. Of all 8 patients with stent thrombosis, 4 (50%) were on DAPT. In this population, definite stent thrombosis while the patient was on DAPT did not occur beyond 3 months from stenting. DAPT, dual antiplatelet therapy. *Stent thrombosis while being on DAPT.

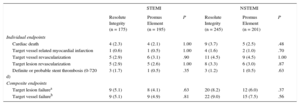

Two-year clinical outcomes were favorable in patients with STEMI and NSTEMI. In patients presenting with STEMI (n = 370), the incidence of TVF (5.1% vs 4.9%; P = .81), target lesion failure, and various individual clinical endpoints was low and similar between the 2 stent arms (Table 3). In addition, in patients presenting with NSTEMI (n = 447), there was no significant difference between stent arms in TVF (9.0% vs 7.5%; P = .56) and other clinical endpoints.

Clinical Outcome of Patients With ST-segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction and non—ST-segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction (2-year Follow-up)

| STEMI | NSTEMI | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resolute Integrity (n = 175) | Promus Element (n = 195) | P | Resolute Integrity (n = 245) | Promus Element (n = 201) | P | |

| Individual endpoints | ||||||

| Cardiac death | 4 (2.3) | 4 (2.1) | 1.00 | 9 (3.7) | 5 (2.5) | .48 |

| Target vessel related myocardial infarction | 1 (0.6) | 1 (0.5) | 1.00 | 4 (1.6) | 2 (1.0) | .70 |

| Target vessel revascularization | 5 (2.9) | 6 (3.1) | .90 | 11 (4.5) | 9 (4.5) | 1.00 |

| Target lesion revascularization | 5 (2.9) | 5 (2.6) | 1.00 | 8 (3.3) | 6 (3.0) | .87 |

| Definite or probable stent thrombosis (0-720 d) | 3 (1.7) | 1 (0.5) | .35 | 3 (1.2) | 1 (0.5) | .63 |

| Composite endpoints | ||||||

| Target lesion failurea | 9 (5.1) | 8 (4.1) | .63 | 20 (8.2) | 12 (6.0) | .37 |

| Target vessel failureb | 9 (5.1) | 9 (4.9) | .81 | 22 (9.0) | 15 (7.5) | .56 |

NSTEMI, non—ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; STEMI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction.

Revascularizations were clinically indicated.

Data are expressed as No. (%).

In the present substudy of the DUTCH PEERS trial, both Resolute Integrity and Promus Element stents were safe and efficacious for treating patients with acute MI. At the 2-year follow-up, the rates of stent thrombosis were low for both devices. The observed low event rates in this acute MI population were mainly attributable to the DES used and not to the concomitant pharmacological therapy, which was quite traditional.28 In addition, we observed no significant between-stent differences in clinical outcome among patients with STEMI and NSTEMI. The DUTCH PEERS trial enrolled a high proportion (45.1%) of patients with acute MI at presentation.20 The proportion of patients with acute STEMI (20.4%)—the group with the highest in-hospital risk after PCI—was even among the highest of all randomized multicenter trials that compared DES in all-comers.8,29–33 The high proportion of patients with acute MI, and in particular STEMI, suggests that selection bias, which is present in almost all randomized clinical trials, may have been relatively small. At the same time, the systematic assessment of post-PCI cardiac markers and electrocardiogram changes, the rigorous monitoring, and the availability of follow-up in as many as 99.9% of patients make potential underreporting of stent thrombosis or other important clinical events fairly unlikely.

DUTCH PEERS is the first randomized study to compare the new-generation Resolute Integrity and Promus Element stents in all-comers. A smaller-sized randomized trial previously compared Promus Element with Xience V (Abbott Vascular; Santa Clara, California, United States) in Spanish all-comer patients.12 The HOST-ASSURE trial compared Promus Element with the second-generation zotarolimus-eluting resolute stent (Medtronic) in East Asian patients. DUTCH PEERS differed from that study (amongst others) by enrolling higher proportions of patients with acute STEMI (20.4% vs 11.2%) and NSTEMI (24.7% vs 17.6%).30 Finally, the SORT OUT all-comer VI trial33 recently compared the Resolute Integrity stent with a bioresorbable polymer DES (Biosensors; Singapore), showing similar outcomes at 1-year.

New-generation Drug-eluting Stent in Acute Myocardial InfarctionPatients with NSTEMI and STEMI share a common pathophysiological substrate, and mid- and long-term mortality rates were shown to be similar following NSTEMI and STEMI.34 Therefore, it is reasonable that several comparative DES studies, as well as the present study, assessed patients with STEMI and NSTEMI together.15,35 Culprit lesions of patients with acute coronary syndromes show a healing response and neointimal DES coverage that may differ from those of patients with stable angina.36 Nevertheless, newer generation DES, more attention has been paid to the clinical outcome of patients with STEMI,14,17,18,37 but, as highlighted by the present study, the event risk may be equally high or even higher in patients with NSTEMI.

Data from randomized studies that assessed new-generation DES in the setting of acute MI were mainly obtained with cobalt-chromium everolimus-eluting Xience V/Promus stents.14–17 At the 1-year follow-up of the EXAMINATION trial, Xience V and bare metal stents showed no significant difference in the primary patient-oriented combined endpoint of all-cause mortality, any recurrent MI or revascularization (11.9% vs 14.2%; P = .19) in a total of 1498 patients with acute STEMI,14 of whom a large proportion was treated via the radial access route.38 Nevertheless, the 1-year rates of target lesion revascularization (2.1% vs 5.0%; P = .003) and stent thrombosis (definite-or-probable: 0.9% vs 2.5%; P = .019) were significantly lower after DES use.14 In addition, at the 2-year follow-up, a particular benefit of everolimus-eluting stent use was found.39 The 5-year follow-up EXAMINATION data have been reported, demonstrating impressive long-term reductions in device-related and patient-related clinical endpoints after treatment with DES compared with bare metal stents.40 In the XAMI trial,16 in which 625 patients with acute MI (96% STEMI) underwent PCI with Xience V or sirolimus-eluting Cypher (Cordis; Warren, New Jersey, United States) stents, the rate of the primary endpoint of major adverse cardiovascular events was significantly lower in Xience V (4.0% vs 7.7%; P = .048). In addition, the definite-or-probable stent thrombosis rate was nonsignificantly lower in Xience V (1.2% vs 2.7%; P = .21). A comprehensive network meta-analysis17 and a mixed treatment comparison analysis of trial level data18 revealed, for the treatment of STEMI with newer-generation DES, a substantially decreased need for repeat revascularization without compromising safety and showed relatively low rates of stent thrombosis in Xience V/Promus stents.

LimitationsThe present study has some limitations. Like many other substudies of large randomized clinical trials, the present post-hoc analysis of the DUTCH PEERS randomized trial should be interpreted with caution. In addition, the findings should be considered hypothesis-generating only. Randomization was not stratified for MI. In the 2 stent groups, many baseline characteristics of patients, lesions, and procedures were similar. Nevertheless, despite the randomization, patients treated with Resolute Integrity stents presented slightly more often with NSTEMI and showed a trend toward more diabetics. On the other hand, patients in the Promus Element stents arm were somewhat more often treated for severely calcified target lesions and more often required stent postdilations. As in all other randomized stent studies that have compared stents with dissimilar angiographic patterns or a difference in radiopacity, it cannot be fully excluded that clinints committeecal eve members, when reviewing coronary angiographies, might have had a notion of the stent used. The study is underpowered for the assessment of low-frequency events (eg, stent thrombosis) in MI subgroups. Data from future dedicated, prospective, randomized trials to compare the modern, flexible durable-polymer stents of the current study in the setting of acute STEMI or NSTEMI will still be of interest. Until such data emerge, the findings of the current study may be of interest to compare the clinical outcome of PCI with new devices, such as polymer-free DES, biodegradable polymer DES and bioresorbable scaffolds,41 when implanted in patients with acute MI.

CONCLUSIONSResolute Integrity and Promus Element stents were both safe and efficacious in treating patients with acute MI. The present 2-year follow-up data underline the safety of using these devices in this particular clinical setting.

FundingThe investigator-initiated, randomized DUTCH PEERS trial was funded by equal research grants from Boston Scientific and Medtronic.

Conflicts of interestC. von Birgelen has been a consultant to Medtronic and Boston Scientific; he received lecture fees from AstraZeneca and MSD. His institution received research grants from AstraZeneca, Biotronik, Boston Scientific, and Medtronic. All other authors declare that they had no conflicts of interest.

- -

First-generation coronary DES were associated with an increased adverse event risk that was particularly high after interventions for acute MI.

- -

Second-generation DES were more biocompatible and showed more favorable safety profiles.

- -

At present, there is a widespread use of novel newer-generation DES that use stent platforms that have undergone substantial changes in design and/or material.

- -

These flexible stent designs may be particularly valuable in patients with MI, as they might reduce device-induced traumas to culprit lesions, but there are scarce data on the safety and efficacy of these DES in the setting of MI.

- -

In the DUTCH PEERS trial, which is the first randomized trial to compare new-generation Resolute Integrity and Promus Element stents in all-comers, many patients (n = 817/1811 [45.1%]) were treated for acute MI.

- -

At 2-years, both stents were found to be safe and efficacious, and the definite stent thrombosis rate was low for both DES (1.0% vs 0.5%; P = .69).

- -

In addition, we observed no significant between-stent difference in clinical outcomes among patients with STEMI and NSTEMI.

- -

Thus, these 2-year outcome data underline the safety of using both newer-generation DES in the setting of acute MI.