INTRODUCTION

This year, we are devoting our Update section to the subject, "Non-coronary arterial disease." Through nine carefully selected review articles, entrusted to internationally recognized experts, we hope to cover, in their entirety and in sufficient depth, the most important aspects of this disease, which is currently a burning issue (Table). The idea is to provide a critical, rigorous update of this fascinating facet of cardiovascular disease, often pushed to the background, or even forgotten.

Atherosclerosis is a progressive systemic disease that affects different vascular beds.1-3 In fact, the coexistence of coronary, cerebral and peripheral involvement is very common.2,3 Aside from certain peculiarities, the risk factors associated with the different sites are similar, the clinical signs depend on the most severely affected territory, and medical treatment (antiplatelet agents, statins, and angiotensin-converting enzyme [ACE] inhibitors) has common beneficial effects in these patients.1-3

Vascular disease is a chronic condition that represents a serious public health problem; however, in view of the foreseen aging of the population, its importance will undoubtedly grow in the immediate future.1-3 Consequently, prevention emerges as a strategy of top priority. Recent data concerning the situation in Spain reveal the tremendous amount of work that remains to be done in order to achieve adequate control of the classical risk factors.4,5 In this respect, equations for the prediction of cardiovascular risk can help to guide prophylactic treatment.6 Moreover, unprecedented advances have recently been made in our ability to directly and noninvasively "visualize" the presence of the disease in multiple vascular beds (global atherosclerotic burden), even in the silent phase. The measurement of the calcium score or the visualization of the atheromatous plaque and the residual lumen in different arterial territories, either by computed tomography or by magnetic resonance, has revolutionized the diagnosis of this disease.7-9 The precision in the anatomical characterization that these techniques now provide in medium-sized and large vessels is simply spectacular. All this information should enable us to optimize our therapeutic efforts in selected patients.

Cerebral Vascular Disease

The aging of the population is having a decisive impact on the incidence and prevalence of cerebrovascular diseases (CVD).10-13 We know that the consequences of stroke, both for the patient and society, are usually devastating. Some systematic reviews reveal truly disturbing data.11 A recent study points out that the incidence of CVD in Europe will increase dramatically in the coming years (from 1 000 000/year in 2000 to 1 500 000/year in 2025), merely as an expression of demographic changes.11 The reduction in age-adjusted rates of cerebrovascular mortality observed over the last four decades will thus be amply surpassed by the net increase in mortality because of the aging of the population.10-13 The incidence of CVD in Spain has been estimated to be between 218 and 364 per 100 000 population among men and between 127 and 169 among women.10,13 In patients over 70 years of age, the estimates are 10-fold higher, while the prevalence in individuals over the age of 65 is 7% in men and 6% in women.10 We must remember that in the brain, aside from the general atherosclerotic process, there is a specific substrate for vascular degeneration. With the deposition of a beta-amyloid substance, known as "cerebral amyloid angiopathy", which can cause recurrent cerebral hemorrhages.14

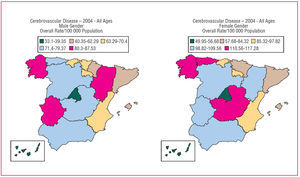

The most recent data (2004) on mortality due to CVD in Spain from the Centro Nacional de Epidemiología (National Center for Epidemiology) are shown in Figure. These data only reflect in-hospital mortality, and it has recently been pointed out that up to two thirds of the deaths due to CVD occur outside the hospital setting. Thus, the overall population mortality due to CVD is as high as 36%.13 Stroke is the leading cause of adult disability, the second leading cause of dementia and the third leading cause of death in industrialized countries. In Spain, CVD are the leading cause of death in women.15

All patients with CVD should receive extensive information on the modification of risk factors, as well as proper medical treatment. A number of studies have demonstrated that treatment with statins reduces the incidence of stroke in high cardiovascular risk patients.16,17 There has also been speculation concerning the "stroke paradox," according to which, despite the fact that epidemiological studies have found no clear relationship between cholesterol concentrations and stroke risk, there are data that clearly show that statin therapy prevents stroke in patients with ischemic heart disease.16,17 Moreover, very recent studies have also demonstrated that, in patients with no known coronary heart disease who have had a stroke or a transient ischemic attack, intensive statin therapy reduces the rate of recurrence.16 This treatment, however, might not be effective, or may even be harmful in patients who have had a hemorrhagic stroke.17

Carotid Disease

The easy access to this artery has made it a highly attractive target for the study of atherosclerosis in general. Thus, incipient carotid atherosclerosis can be analyzed with precision using ultrasound to measure the intima-media thickness of posterior wall of the common carotid artery.2,3 Values over 1.1 mm not only are associated with the presence of atherosclerosis at other sites, but are also predictive of cardiovascular risk.2,3

In 1951, Fisher reported the pathological relationship between the carotid atheromatous plaque and ipsilateral stroke.18 Since then, carotid endarterectomy has been the surgical intervention most widely performed for stroke prevention.19 In contrast to what we have learned in ischemic heart disease, where the demonstration of the presence of ischemia is universally considered to be an indispensable requirement for the indication for revascularization, in carotid disease, the mere presence of an angiographically severe lesioneven "asymptomatic"justifies the intervention.19 Its status as a mature technique, acquired over more than 5 decades, supports the results of carotid endorterectomy. However, in recent years, percutaneous interventional procedures have aroused a great amount of expectation.19 In this respect, carotid stent implantation has been shown to be a feasible alternative in selected high-risk patients.20 However, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has approved stent placement only in symptomatic patients, with over 70% internal carotid artery stenosis and at risk for developing complications following endarterectomy. At the present time, there is an intense debate concerning the real value of this technique in patients who do not present high surgical risk. A recent Cochrane systematic review concluded that carotid endarterectomy should continue to be considered the treatment of choice in this disease.21 More recently, two extensive randomized studies have had to be suspended prematurely, sowing new doubts about the efficacy of percutaneous treatment as an alternative to surgery.22,23 Nevertheless, we should remember that, in some of these studies, the interventional procedure was performed by personnel with limited previous experience and that the systems for preventing distal embolization were not systematically employed.19,22,23 Recent data suggest that the morphological features of the plaque (identified by noninvasive means) could help predict the risk of embolization after the intervention and efforts are presently being made to improve the selection of the patients who might benefit from this technique.24 The continuing technological advances, together with new ongoing randomized studies, demonstrate that, with regard to revascularization in carotid artery stenosis, the swords remain drawn.

Peripheral Arterial Disease

Peripheral arterial disease (PAD) is generally understood to be the obstruction of the blood flow in any arterial territory, with the exception of the coronary and cerebral territories.2,3 The area of interest extends to the abdominal aorta, the renal and mesenteric arteries or, more specifically, to the lower extremities. Peripheral arterial disease usually coexists with coronary and cerebrovascular disease.2,3,25 Thus, the risk of myocardial infarction, stroke and death in patients with PAD is between two and four times higher, while approximately one third of the patients with coronary or cerebrovascular disease also have PAD.2,3,25 The early diagnosis and treatment of PAD reduces the incidence of renal insufficiency, mesenteric ischemia, aortic aneurysm rupture and amputations. Although atherosclerosis is the major cause of PAD, we should take into consideration other degenerative diseases (Marfan syndrome, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome), fibromuscular dysplasia, vasculitis (large vessels [Takayasu's disease and Behçet's syndrome], medium-sized vessels [Kawasaki disease and Churg-Strauss syndrome] and small vessels [lupus and rheumatoid arthritis), and the prothrombotic and vasospastic diseases as possible possible etiologies.2,3

The prevalence of PAD is elevated and it has been estimated to affect up to 20% of the patients over 65 years of age, in whom it is usually asymptomatic.2,3 Although the cardinal symptom is intermittent claudication, the ankle-brachial index, at baseline and following exercise, is much more sensitive and thus provides a clearly cost-effective measure for the detection of PAD.2,3,26 This index is calculated as the highest pressure in each lower limb (dorsal pedal or posterior tibial artery), divided by the highest pressure in either of the two arms (normal: between 1 and 1.29). The ankle-brachial index not only is useful for the diagnosis of PAD, but for the prediction of overall cardiovascular risk, as well.2 In turn, stress testing or, better still, the six-minute walk test enables the objective measurement of the functional limitation of patients with PAD.2

Aortic Disease

The role of the cardiologist in the study of thoracic aortic disease has never been questioned,27 and this subject will be reviewed in two specific sections of this Update. Here, we will only mention the interest aroused recently by the new "endovascular" treatments, aided by modern imaging techniques and by the creation of multidisciplinary teams,28 which make it possible to optimize the diagnosis and treatment of thoracic aortic diseases.

However, until now, the involvement of the cardiologist in abdominal aortic disease has been very limited. Thus, we should remember that the prevalence of abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAA) (anteroposterior diameter greater than 3 cm) also depends on age (1.3% in men aged 45 to 55 years; 12.5% in men over 75).2,3 The systematic performance of ultrasonographic evaluation in all male smokers over the age of 65 years has recently been recommended.29 Atherosclerosis in the thoracic aorta and an abnormal intima-media thickening of the carotid artery are common findings in patients with AAA, a circumstance that again reflects a generalized atherosclerotic process.2,3 In their natural history, AAA undergo gradual dilation (the larger the aneurysm, the faster this process) and thrombosis. The most feared complications are rupture, ischemic events and compression or erosion of adjacent structures. The cumulative risk of rupture depends on the size (20% when the aneurysm is greater than 5 cm and 40% when it measures over 6 cm) and the consequences are catastrophic, with a mortality rate of more than 90%.2 Thus, the class I recommendation is that patients with infrarenal or juxtarenal AAA measuring 5.5 mm or larger should undergo repair, and the class IIa recommendation is that repair should be performed when it is greater than 5 cm.2 Moreover, beta-blockers are indicated to reduce the surgical risk in patients with coronary heart disease (class I recommendation) and the rate of expansion (class IIb recommendation).2

The surgical outcome in patients with AAA has been extensively assessed. Although recent data30,31 indicate that, in anatomically suitable patients, endovascular treatment can reduce early mortality, the long-term duration of the effects of this treatment has yet to be established.31 On the other hand, since associated coronary artery disease is the major cause of death in patients with AAA, its correct identification and treatment is of utmost concern. However, the simple optimization of the medical treatment appears to be the most important aspect.32 In an elegant randomized study involving selected patients with stable coronary artery disease who were considered to be at high risk,31 intensive medical treatment (beta-blockers, antiplatelet agents, statins, and ACE inhibitors) proved to be as effective as a systematic myocardial revascularization strategy in reducing adverse ischemic events following major vascular surgery (for AAA in 33% and for PAD in 67%).32

Other problems involving the abdominal aorta are not as clearly defined. Mesenteric ischemia can be due to arterial stenosis (generally multiple because of the abundant collateral circulation in this territory) or to conditions associated with severe hemodynamic compromise.2 Severe mesenteric ischemia generally leads to intestinal necrosis, which is usually fatal despite early aggressive treatment.2 Clinical practice guidelines insist on the limited information from controlled studies of this vascular territory and on the need to encourage the performance of properly designed studies.2

Renal Vascular Disease

Renal artery stenosis is attributable to atherosclerosis in 90% of the cases (proximal involvement) and to fibromuscular disease in the remaining 10% (mid-distal involvement).2 In some oriental countries, many cases are secondary to Takayasu's disease. The prevalence of renal artery stenosis is up to 7% among patients over 65 years of age. It is frequently associated with hypertension and renal insufficiency.2 We should keep in mind that renovascular hypertension continues to be the most common cause of correctable hypertension. In selected patients, stent placement is superior to balloon angioplasty, both in controlling the pressure and in reducing the rate of restenosis.2 However, this therapy requires a clear clinical indication: refractory hypertension, renal insufficiency, acute pulmonary edema, etc. Moreover, the degree of renal function recovery following revascularization is usually limited and highly variable.

CONCLUSIONS

The times for discussion as to which specialist is best prepared for dealing with the different aspects of non-coronary arterial disease are over. Multidisciplinary teams of qualified professionals in different aspects of this disease are now the rule. Nevertheless, as we will see in this Update, the evidence that the cardiologist should play a fundamental role in prevention, diagnostic and therapeutic strategies in these patients is unquestionable.

In this systemic disease, which is characterized by diffuse involvement and, at the present time, by inexorable progression, there is a clear consensus as to the fact that our priority should focus on optimizing preventive measures. The new imaging techniques have revolutionized our diagnostic capabilities, but rather than favoring the diagnosis of findings with no clear clinical correlation, they should rise to the challenge of being incorporated into new diagnostic algorithms that make it possible to improve patient stratification and enable early aggressive treatment in selected cases. Finally, the modern endovascular techniques have provided therapeutic solutions that, until recently, were inconceivable. However, as was aptly pointed out in a recent editorial,33 our enthusiasm for embracing "the new" should not obscure our ability to critically analyze their efficacy with respect to more conventional treatments.

The interest of the cardiologist in non-coronary arterial disease is evident. We are convinced that, as in preceding years,34,35 the reading of this new Update of Revista Española de Cardiología will not only have an impact in the continuing education setting, but that, in addition, it will raise renewed scientific interest that will facilitate a better understanding of certain aspects of cardiovascular diseases and their treatment that are frequently forgotten, and that, ultimately, the knowledge acquired will result in improvements in the clinical care of our patients.

Correspondence: Revista Española de Cardiología.

Sociedad Española de Cardiología.

Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe, 5-7. 28028 Madrid. España.

E-mail: rec@revespcardiol.org