The number of older patients with congestive heart failure has dramatically increased. Because of stagnating cardiac transplantation, there is a need for an alternative therapy, which would solve the problem of insufficient donor organ supply. Left ventricular assist devices (LVADs) have recently become more commonly used as destination therapy (DT). Assuming that older patients show a higher risk-profile for LVAD surgery, it is expected that the increasing use of less invasive surgery (LIS) LVAD implantation will improve postoperative outcomes. Thus, this study aimed to assess the outcomes of LIS-LVAD implantation in DT patients.

MethodsWe performed a prospective analysis of 2-year outcomes in 46 consecutive end-stage heart failure patients older than 60 years, who underwent LVAD implantation (HVAD, HeartWare) for DT in our institution between 2011 and 2013. The patients were divided into 2 groups according to the surgical implantation technique: LIS (n = 20) vs conventional (n = 26).

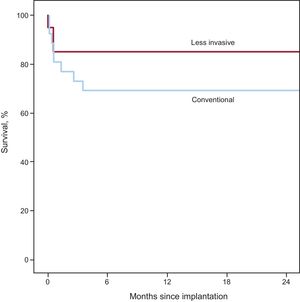

ResultsThere was no statistically significant difference in 2-year survival rates between the 2 groups, but the LIS group showed a tendency to improved patient outcome in 85.0% vs 69.2% (P = .302). Moreover, the incidence of postoperative bleeding was minor in LIS patients (0% in the LIS group vs 26.9% in the conventional surgery group, P < .05), who also showed lower rates of postoperative extended inotropic support (15.0% in the LIS group vs 46.2% in the conventional surgery group, P < .05).

ConclusionsOur data indicate that DT patients with LIS-LVAD implantation showed a lower incidence of postoperative bleeding, a reduced need for inotropic support, and a tendency to lower mortality compared with patients treated with the conventional surgical technique.

Keywords

Modern conservative therapies for heart failure have improved outcomes in adult patients.1 Despite medical advances in treating this condition, the disease itself remains a progressive condition. Projections estimate that by 2020 the number of patients dying from cardiovascular disease will increase to more than 7 millions worldwide.2,3 Cardiac transplantation as a therapeutic option is strongly restricted by donor organ shortage and is therefore mainly limited to patients younger than 60 years.4,5 In times of demographical changes, reflected in population aging, there is an urgent need for alternative and effective therapies to treat end-stage heart failure in elderly patients.6 Thus, left ventricular assist devices (LVADs) are now widely applied as destination therapy (DT).7–13 However, DT patients have an increased perioperative risk with high mortality.8 In their seminal article, Slaughter et al.14 showed that the treatment with continuous-flow LVAD improved the survival of DT patients by up to 58% after 2 years of being on pump. In that study, all patients were underwent the standard surgical technique, which is by a full sternotomy. At that time, this surgical approach was mandatory due to the increased pump size and the lack of surgical alternatives. Of note, a full sternotomy involves major operative trauma with higher risks of postoperative respiratory failure, longer intrahospital stay, and perioperative bleeding.15–17 In LVAD surgery, it is especially critical to avoid bleeding, since the therapy itself involves alterations of hemostasis, such as acquired von Willebrand syndrome, which also increases the perioperative bleeding risk.18 According to a literature review, the incidence of bleeding requiring surgery and extended inotropic support ranges from 30% to 40% in DT patients undergoing by full sternotomy.14,19–21 Moreover, a full sternotomy implies a full opening of the pericardium, which abrogates the natural confinements of the right ventricle, thus contributing to the danger of postoperative right heart failure once LVAD is started.22

A key feature of the newest LVADs is their remarkably reduced pump size.23,24 This has facilitated the development of less invasive surgery (LIS) techniques for the implantation, explantation, and exchange of ventricular assist devices.25–28 The new era of LIS-LVAD implantation is expected to improve therapy outcomes by reducing such important operative complications as bleeding or right ventricular failure.29,30

This study reports the first long-term results of DT patients with end-stage heart failure undergoing a minimally invasive technique for continuous-flow pump implantation.

METHODSIn 2011, our group developed a minimized LVAD implantation technique.22 Between 2011 and 2013, we performed a prospective study of 46 consecutive patients older than 60 years, who required LVAD surgery as DT because they were ineligible for cardiac transplantation. All patients were operated on by the same surgical team that decided which technique to use for implantation. The data of 20 patients that received LIS-LVAD implantation (HVAD, HeartWare Inc, Miami Lakes, United States) were compared with those of a control group of 26 patients who underwent conventional sternotomy. Clinical indication criteria for LVAD implantation were as follows: significantly impaired cardiac function (left ventricular ejection fraction < 30%) with cardiac index < 2.2 L/min/m2 refractory to medical therapy, including inotrope dependency. All patients with previous cardiac surgery and/or concomitant cardiac surgery were excluded from the study. Extended inotropic support was defined as inotropic therapy for ≥ 14 days after LVAD implantation. Respiratory failure was defined as pulmonary insufficiency requiring intubation and ventilation for a period of 96hours or more at any time during the postoperative stay due to blood oxygen saturation < 96% while receiving a fraction of inspired oxygen ≥ 0.50. Renal failure was defined by the need for dialysis.

The LIS procedure involves 2 steps: first, the LVAD pump is inserted through an anterolateral thoracotomy (fifth or sixth intercostal space). Second, the surgical team performs an upper J-shaped hemisternotomy to the third intercostal space to anastomose the LVAD outflow graft end-to-side to the ascending aorta.22 Finally, all patients received the same LVAD system (HVAD, HeartWare) and were implanted using cardiopulmonary bypass. The implantation was followed by a 2-year follow-up, during which the patients visited the outpatient clinic 4 times a year.

The investigation conforms to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients provided written informed consent and the study was approved by the local institutional review board. Postoperative medical care was maintained according to usual practice.

Statistical AnalysisThe statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 20.0 (IBM SPSS Statistisics, IBM Corp, Armonyk New York, United States). We used unpaired t test, the Fisher exact test, the Pearson chi-square test, and the Kaplan-Meier survival estimation for statistical analysis. Survival curves were compared using the log-rank test. Differences were considered significant at P < .05. All continuous data are summarized as mean ± standard deviation.

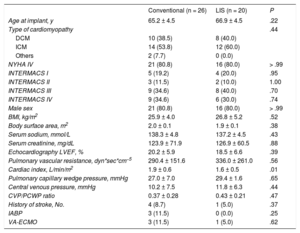

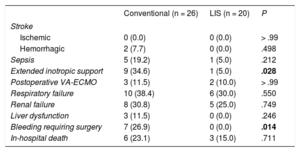

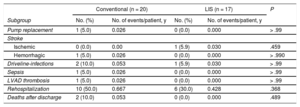

RESULTSBaseline characteristics are summarized in Table 1 and were similar in both patient groups. There was a predominance of men with mean preoperative ejection fractions measured by transthoracic echocardiography of 20.2% (conventional) and 18.5% (LIS). The right heart catheter showed mean cardiac indices of 1.9 L/min/m2 (conventional) and 1.6 L/min/m2 (LIS) with mean pulmonary vascular resistances of 336.0 dyn*s*cm−5 (LIS) and 290.4 dyn*s*cm−5 (conventional), respectively. Mean pulmonary capillary wedge pressure ranged from 29.4mmHg (LIS) to 27.0mmHg (conventional). Preoperative extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) support was performed in 3 patients in the conventional group and in 1 in the LIS group. Survival curves for both groups are presented in Figure. In-hospital survival was 85.0% (LIS) and 76.9% (conventional) (P = .71). The 2-year survival was 85.0% for LIS patients and 69.2% for conventional patients (P = .302). Survival curves were compared using the Mantel-Cox test and showed P = .242. The causes of death in the conventional group were intracranial bleeding (25.0%), sepsis (25.0%), multiorgan failure (25.0%), right heart failure (12.5%), and bleeding related to surgery (12.5%). In the LIS group death was triggered by right heart failure (33.3%), sepsis (33.3%), and multiorgan failure (33.3%). An overview of all adverse events is shown in Table 2 and Table 3. There was a lower incidence of prolonged inotropic support in the LIS group (5%) compared with 34.6% in patients in the conventional group (P = .028). Total intensive care unit stay was 15.2 ± 17.1 days in conventionally treated patients and 12.1 ± 12.1 days in the LIS group (P = .513). The overall number of nonsurvivors in the intensive care unit was 19.2% in the conventional group and 15.0% in the LIS group (% referred to the total amount of nonsurvivors in each group). In the conventional group, all 3 patients with previous ECMO treatment underwent postoperative extracorporeal circulation. In the LIS group, there were 2 postoperative ECMO patients; 1 of these received ECMO before LVAD implantation. Postoperative ECMO treatment time was longer in the conventional group: 10.0 ± 5.9 days vs 5.0 ± 5.7 days in LIS patients (P = .381). In the LIS group, none of the patients required reoperation due to postoperative bleeding, in contrast to bleeding requiring surgery in 26.9% of the conventional group (P < .05). Left ventricular assist device-related infections were documented in 4% (conventional) and 0% (LIS) of all patients (P > .99). There was only 1 patient in the conventional group who required pump exchange due to thrombus formation.

Baseline Characteristics

| Conventional (n = 26) | LIS (n = 20) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at implant, y | 65.2 ± 4.5 | 66.9 ± 4.5 | .22 |

| Type of cardiomyopathy | .44 | ||

| DCM | 10 (38.5) | 8 (40.0) | |

| ICM | 14 (53.8) | 12 (60.0) | |

| Others | 2 (7.7) | 0 (0.0) | |

| NYHA IV | 21 (80.8) | 16 (80.0) | > .99 |

| INTERMACS I | 5 (19.2) | 4 (20.0) | .95 |

| INTERMACS II | 3 (11.5) | 2 (10.0) | 1.00 |

| INTERMACS III | 9 (34.6) | 8 (40.0) | .70 |

| INTERMACS IV | 9 (34.6) | 6 (30.0) | .74 |

| Male sex | 21 (80.8) | 16 (80.0) | > .99 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 25.9 ± 4.0 | 26.8 ± 5.2 | .52 |

| Body surface area, m2 | 2.0 ± 0.1 | 1.9 ± 0.1 | .38 |

| Serum sodium, mmol/L | 138.3 ± 4.8 | 137.2 ± 4.5 | .43 |

| Serum creatinine, mg/dL | 123.9 ± 71.9 | 126.9 ± 60.5 | .88 |

| Echocardiography LVEF, % | 20.2 ± 5.9 | 18.5 ± 6.6 | .39 |

| Pulmonary vascular resistance, dyn*sec*cm−5 | 290.4 ± 151.6 | 336.0 ± 261.0 | .56 |

| Cardiac index, L/min/m2 | 1.9 ± 0.6 | 1.6 ± 0.5 | .01 |

| Pulmonary capillary wedge pressure, mmHg | 27.0 ± 7.0 | 29.4 ± 1.6 | .65 |

| Central venous pressure, mmHg | 10.2 ± 7.5 | 11.8 ± 6.3 | .44 |

| CVP/PCWP ratio | 0.37 ± 0.28 | 0.43 ± 0.21 | .47 |

| History of stroke, No. | 4 (8.7) | 1 (5.0) | .37 |

| IABP | 3 (11.5) | 0 (0.0) | .25 |

| VA-ECMO | 3 (11.5) | 1 (5.0) | .62 |

BMI, body mass index, CVP, central venous pressure; DCM, dilated cardiomyopathy; IABP, intra-aortic balloon pump, ICM, ischemic cardiomyopathy; LIS, less invasive surgery; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; NYHA, New York Heart Association; PCWP, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure; VA-ECMO, venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.

Values are expressed as mean ± standard deviation or No. (%).

Adverse Events After Implantation (In-hospital Outcome)

| Conventional (n = 26) | LIS (n = 20) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stroke | |||

| Ischemic | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | > .99 |

| Hemorrhagic | 2 (7.7) | 0 (0.0) | .498 |

| Sepsis | 5 (19.2) | 1 (5.0) | .212 |

| Extended inotropic support | 9 (34.6) | 1 (5.0) | .028 |

| Postoperative VA-ECMO | 3 (11.5) | 2 (10.0) | > .99 |

| Respiratory failure | 10 (38.4) | 6 (30.0) | .550 |

| Renal failure | 8 (30.8) | 5 (25.0) | .749 |

| Liver dysfunction | 3 (11.5) | 0 (0.0) | .246 |

| Bleeding requiring surgery | 7 (26.9) | 0 (0.0) | .014 |

| In-hospital death | 6 (23.1) | 3 (15.0) | .711 |

LIS, less invasive surgery; VA-ECMO, venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.

Adverse Events After Implantation (Postdischarge Outcomes)

| Conventional (n = 20) | LIS (n = 17) | P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subgroup | No. (%) | No. of events/patient, y | No. (%) | No. of events/patient, y | |

| Pump replacement | 1 (5.0) | 0.026 | 0 (0.0) | 0.000 | > .99 |

| Stroke | |||||

| Ischemic | 0 (0.0) | 0.00 | 1 (5.9) | 0.030 | .459 |

| Hemorrhagic | 1 (5.0) | 0.026 | 0 (0.0) | 0.000 | > .990 |

| Driveline-infections | 2 (10.0) | 0.053 | 1 (5.9) | 0.030 | > .99 |

| Sepsis | 1 (5.0) | 0.026 | 0 (0.0) | 0.000 | > .99 |

| LVAD thrombosis | 1 (5.0) | 0.026 | 0 (0.0) | 0.000 | > .99 |

| Rehospitalization | 10 (50.0) | 0.667 | 6 (30.0) | 0.428 | .368 |

| Deaths after discharge | 2 (10.0) | 0.053 | 0 (0.0) | 0.000 | .489 |

LIS, less invasive surgery; LVAD, left ventricular assist devices.

For the “rehospitalization” subcategory, the rates were calculated on the basis of LVAD-related rehospitalization within 12 months after the initial hospital discharge.

Less invasive surgery techniques have contributed to the reduction of surgical trauma in cardiac surgery. Moreover, in general cardiac surgery, LIS approaches reduce complication rates, such as postoperative bleeding, postoperative pain, and respiratory insufficiency.15 In LVAD therapy, LIS is fairly recent with only a few reports describing early outcomes.29–31 To date, there is no evidence that LIS-LVAD implantation can be performed in high-risk DT patients safely. Thus, the present study was undertaken to collect the relevant data for risk estimation of LVAD surgery in these patients. Recently, our group developed a less traumatic LVAD implantation technique consisting of 2 principal steps: upper J-shaped hemisternotomy and left-sided anterolateral thoracotomy.22 The major advantage of this approach is that the pericardium remains mainly closed, preserving the natural limits of the right ventricle. This enables right heart function to be retained, by avoiding right ventricular over-dilatation during the LVAD onset. Right ventricular impairment is commonly managed by increased inotropics during the early postoperative phase. Thus, we included this in our investigation. Our data show that there was a significantly lower incidence of prolonged inotropic support in the minimally invasive group. Furthermore, all these patients were successfully compensated under this treatment. In those patients (n = 4) who had had global preoperative cardiac decompensation and received ECMO treatment prior to implantation, there was no statistically significant difference between the 2 groups. Nevertheless, the length of ECMO treatment showed a tendency to be shorter in the LIS group. Weaning from extracorporeal circulation was also easier in the LIS group; in addition, the patients were hemodynamically more stable. The LIS group benefited from another advantage of the operative technique, namely, none of them had to be reoperated due to perioperative bleeding. This can be explained by the considerably reduced incisions and less surgical trauma. Furthermore, the LIS technique allows the performance of important surgical steps such as sewing ring sutures off-pump without full heparinization. In addition to allowing smaller incisions, this contributed to decreasing blood loss in the LIS group. The analysis of the control group showed that the incidence of bleeding-related-surgery in the conventional sternotomy group was comparable to those described previously.23

The LIS approach also prevented tissue adhesions for future surgery, although this factor may be of secondary importance in DT patients. Thus, redo operations may become less risky after a LIS-LVAD implantation.

Although our analysis did not reveal a statistically significant difference in mortality, the Kaplan-Meier survival curve shows a strong tendency in favor of the LIS approach, with mortality being 85% vs 69% in the first 2 postoperative years.

LimitationsA major limitation of the underlying study is that there was no randomization. Insofar as the purpose of the study was to investigate the safety of LIS in LVAD implantation, we designed a prospective observational study. Thus, our results should be evaluated in this context. Since analysis of baseline characteristics revealed no differences between the 2 groups, we consider the study design suitable to clarify this question. Even if improvement in survival was not statistically significant in the LIS group, we demonstrate that LIS-treated patients had a lower incidence of surgical complications than the conventional group. As this is considered to be the first study of the kind, these preliminary findings will contribute to launching multicenter randomized trials with an increased sample power. Broadening our experience to other centers with a larger number of overall treated patients could help to prove our observations.

CONCLUSIONSOur data suggest that the implantation of a miniaturized continuous-flow device by LIS is safe, feasible, and associated with several positive effects including protection of the right ventricle and a lower incidence of postoperative bleeding. Despite the preliminary character of the results obtained in this study, they indicate that DT patients older than 60 years, undergoing LVAD implantation, can achieve a 2-year survival rate higher than 80%. This creates a need for multicenter studies with larger numbers of patients to investigate whether the rates can be statistically preserved. However, since the miniaturization process of LVADs is ongoing, it is likely that in future LIS-LVAD surgery will gain more and more importance.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTS.V. Rojas, M. Avsar, and J.D. Schmitto are consultants for HeartWare Inc and SJM.

- –

Left ventricular assist device therapy is gaining importance in the treatment of congestive heart failure. Originally designed as bridge-to-transplant strategy, novel devices have lately been used for long-term support. Moreover, due to demographic changes, the number of elderly heart failure patients ineligible for cardiac transplantation will grow, which will in turn increase the number of DT candidates. However, this target group has a high level of comorbidity with increased perioperative mortality.

- –

Novel surgical approaches that minimize operative trauma might help to improve early survival by decreasing surgical complications. The present study is the first of its kind to compare LIS with conventional LVAD implantation in DT patients. Our results show that LIS-LVAD implantation is feasible and safe in DT.

SEE RELATED CONTENT: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rec.2017.08.003, Rev Esp Cardiol. 2018;71:2–3.