To the Editor,

Spontaneous coronary artery dissection is an uncommon cause of myocardial ischaemia. It has conventionally been described in young women without cardiovascular risk factors (CVRF).1 The clinical manifestation of this condition varies between sudden death and acute coronary syndrome (ACS). The appearance of a haemopericardium is rare.2, 3, 4

The patient is a 66-year-old female with hypertension that sought treatment for typical tightness in the chest at rest and vegetative reactions over a period of 2h. Upon arrival, arterial blood pressure was 165/88mmHg; examination revealed truncal obesity and grade II/VI systolic murmur in basal foci. An ECG showed elevations in the V2-6 and the ST segment of the inferior face. We performed fibrinolysis using 9000 U of tenecteplase, since the door-to-balloon time was estimated >90min and was found within the first 2h of evolution. Enoxaparin, acetylsalicylic acid, nitroglycerine, and morphine were administered simultaneously. An emergency echocardiogram demonstrated akinesis of the apex and anterior face, and the ejection fraction was estimated at 40%. We also observed a small posterior pericardial effusion. The persistence of the symptoms and consistently abnormal ST-segment led to salvage angioplasty. Before arriving at the operating room, the patient went into pulseless electrical activity, and died when reanimation failed.

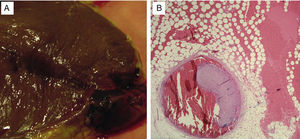

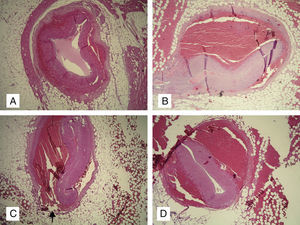

A clinical biopsy revealed haemopericardium with a pressure of 650ml. We observed a partially organised haematoma 1.5cm from the apex (Figure 1A) in relation to the anterior descending artery (Figure 1B). The ventricular wall and intraventricular septum were intact. The middle portion of the anterior face and the apex of the left ventricle had the appearance of an acute infarction. Serial histological sections demonstrated extensive dissection of the anterior descending artery (Figure 2A and B), which extended outside of the external elastic lamina (Figure 2C and D) and broke the vessel wall (Figure 2C, arrow). Atheromatous plaques were not observed.

Figure 1. A: Macroscopic view of the apical subepicardial haematoma. B: Dissection of the anterior descending artery, with an intramural haematoma which compresses the lumen (H-E, ×10).

Figure 2. A-D: Dissection of the anterior descending artery outside of the external elastic lamina. Arrow: ruptured adventitia (H-E, ×10).

Optimal treatment for spontaneous coronary artery dissection is not well defined. Conservative medical treatment has been efficient in asymptomatic cases with haemodynamic stability and in the absence of residual ischaemia. Heart procedures with stents have been used in localised dissections,2 whereas surgery has been considered for cases involving the coronary artery or multiple vessels.1, 3 The role of fibrinolysis in this condition is controversial: a favourable effect could be expected by dissolving the intramural haematoma.5 However, the same treatment could extend the dissection,6 with the consequent increase in the risk of coronary rupture into the pericardium. Early reperfusion is the treatment of choice for ACS with ST-segment elevation (ACS-STE). The fibrinolysis value is supported by clinical practice guidelines, above all when performed early or when a primary angioplasty is delayed, and is still the most commonly used type of reperfusion. In any case, an ACS-STE in a young woman without CVRF should make us consider performing a coronarography on an individual basis, even when this implies slightly delaying the time to reperfusion, in order to avoid complications in the fibrinolytic treatment.

We have presented this case primarily because of its rare occurrence, both due to it having appeared in a middle-aged woman with CVRF (arterial hypertension and obesity) as well the appearance of a haemopericardium secondary to a ruptured coronary artery that constitutes the fourth case of its kind,3, 4 since the first case was described by Pretty in 1931.2 We believe that the fibrinolytic treatment was key in the appearance of the haemopericardium. We also consider that necropsies, greatly underused in our field, should be performed more frequently in order to complement the physician's efforts at confirming the aetiology, as in our case.

Corresponding author: almendrode@secardiologia.es